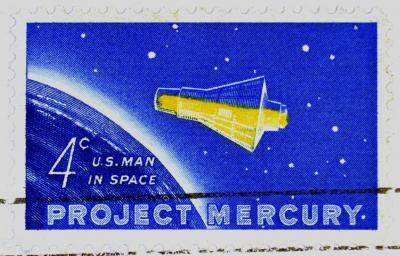

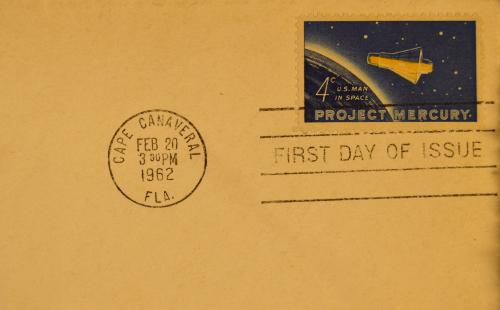

This simple, elegant stamp’s story combines many elements of the early U.S. space program: pride, fear of failure, concern for public relations and a culture of secrecy.

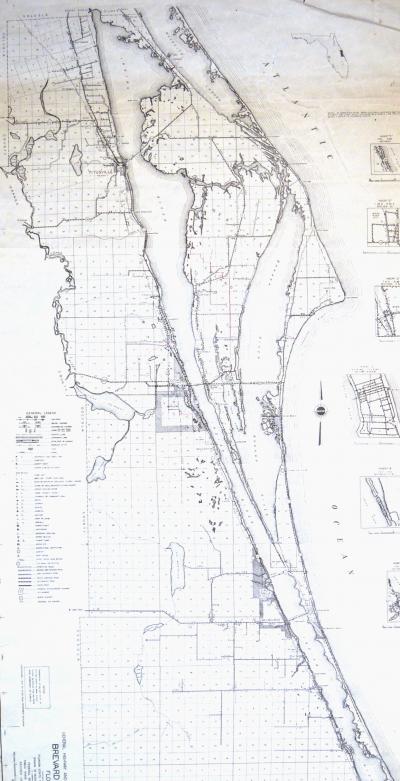

The story starts with geography.

Cape Canaveral juts out into the Atlantic Ocean. It is a perfect place to locate a space center and launch complex as America needed to do in the early 1960’s to compete in the “Space Race” with the Soviet Union. It facilitated launches to the east over open water, and was about as far south as you could get (to be close to the equator and gain launch speed from the Earth’s rotation) and still be on American soil.

Also, it was isolated. The government could build what facilities were needed and keep them secure from unwanted visitors and prying enemy eyes. Tour guides still refer to the gator infested wetlands as a big part of Kennedy Space Center’s security system.

In short, this part of Brevard County, Florida, played (and plays) a pivotal role in the space program.

For this story we focus on the sixth Mercury mission, the February 20, 1962 flight of Friendship 7 and of John Glenn, the first American to orbit the earth, three times in a nearly five hour journey that ended with a safe splash-down in the Atlantic Ocean.

That landing brings us back to our stamp.

Months before the mission, the U. S. Post Office Department, now the U.S. Postal Service (USPS), decided to issue a commemorative stamp and arrange for first day cancellations at Cape Canaveral. These are items highly prized by collectors as well as a way for the general public to take part in a significant historical event.

If the mission went well, that is. If it failed the stamps and all the arrangements would have to vanish without a trace. So everything was done in secret.

The stamp’s designer, Charles R. Chickering, took ‘vacation’ and worked from home.

The engravers also took ‘vacations’. The one who did the picture came in to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing when everyone else went home at night and the one who did the lettering came in on weekends. In 2005 the USPS recounted: “...a rumor was spread that a new multicolor Giori press was locked away for printing test runs of multicolored money. In fact, the new press was being used to print the Project Mercury stamp.”

The stamps were eventually distributed to 305 post offices around the nation, in sealed bags addressed to the postal inspectors and marked secret.

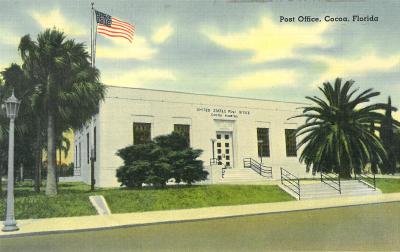

Now, about that first day cancellation. The Post Office wanted to be able to post mark them Cape Canaveral. Remember the line about “isolated”? There was no post office in Cape Canaveral.

The closest Post Office was the one in Cocoa, built in the 1930’s as a WPA project, and now, as luck would have it...

the Headquarters for the Florida Historical Society and home of the Library of Florida History.

But, Cocoa is not Cape Canaveral. To have an honest first day cancellation from the Cape, some canceling machines from Cocoa were loaded into a van and driven out to the Cape for use in an official ‘temporary’ facility.

At 3:30 p.m. local time, Feb. 20, 1962, the word came of Glenn’s safe landing, and the call came from Washington, D.C. “open the bags.” At the Cocoa facility the stamps were dragged out of the vault (that now houses the FHS’s rare books collection) and the sales began.

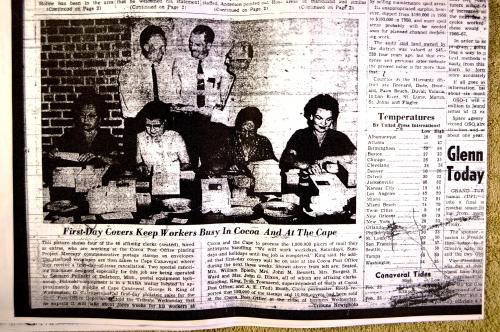

Cocoa Postmaster A.E. (Ted) Booth sold the first commemorative sheet to a salesman, Allan F. Schultz of Jacksonville, a moment now only preserved in a photocopied microfilm image of the local newspaper.

Another image confirms the official cancellation activity at both the Cocoa and Cape facilities. But, say some old timers knowingly, it is likely some of the “Cape Canaveral” post marks were applied in the Cocoa building.

What if Glenn had not made it back?

The plan was for all the stamps to be destroyed and no one would ever know about the project. Well, not exactly ‘no one’; about 400 individuals were in on the plan. But, it was a different time. In December, 1961, the original scheduled date for the flight, a newspaper reported rumors of the secret stamp. The Post Office dismissed the rumors, and all indications are the sale in February came as a surprise.

The whole scheme was a bit of a gamble. The same could be said of the space program. But, at the time and even in retrospect, it was worth it. It was a way to commemorate the astronauts, engineers and all the thousands of workers who were involved in the efforts. It was also a way to involve the millions of citizens enthralled by the effort to slip the bounds of gravity.

One of those was Connie Kennedy (nee Conrader) who, along with her husband Buddy,

was raising a family in southern Brevard County, where the presence of rockets was a given.

The Library of Florida History now has a first day cancellation in its collection, a gift from Connie and Buddy’s daughter

Julie Wilkinson, who, as luck would have it, is a Florida Historical Society volunteer. She says she found the card “tucked in the family Bible” when she was settling her parents estate. She agrees with her older sister Janna that “my mother would have been the one to get the stamp. It makes sense because she was enthralled with the space programs from the earliest days, including the Soviets’ space program.”

The rockets were part of growing up. “We’d start by watching the launches on the TV, with its grainy black and white picture. Once we saw it lift off, we would go outside and watch the rocket’s engines burn bright red and yellow, leaving a white contrail in its path.

“I don’t think Mom ever missed a launch. I’m happy for her sake that she was able to witness history doing something she loved.”