When you read the terms “digital history” or “digital humanities,” you might think of online access to scanned primary source documents such as journals, photographs, or maps. While that’s important, there’s much more to digital history.

“We can interact with the public in a way we couldn’t before,” says Connie Lester, director of the RICHES Project in the public history program at the University of Central Florida, an interdisciplinary effort that records and preserves the documents and stories of Florida communities, businesses, and institutions.

“The public then becomes involved in the collection and interpretation of the history,” says Lester. “The digital tools allow us to do that. The digital tools allow us to see things that are hard to explain in a text fashion.”

Historians and their students are creating exciting digital history and humanities projects using cutting edge technology such as new audio visual recording and editing software to create podcasts and blogs; and 3-D imaging of objects, artifacts, and historic sites.

The University of South Florida St. Petersburg has posted online a 3-D image of the Cocoa Canoe, recently uncovered by hurricane Irma. Anyone can find the image online and spin the canoe around to view it from any angle.

Laurie Taylor, digital history librarian at the University of Florida, has helped to create interactive maps of Florida and the Caribbean.

“Digital history and digital humanities is opening up possibilities for all of us,” says Taylor. “With new tools, with new resources, we can bring those to bear using our humanities expertise which is speculative, which is imaginative, which is creative.”

“These powerful new tools allow us to look at big data sets and look for patterns, hidden patterns, in texts, in data, and that’s exciting because this is work we could not do without a computer,” says Scot French, professor of digital and public history at the University of Central Florida. “One of our M.A. thesis candidates, Holly Baker, is doing a really exciting project where she’s tracking the song collecting journeys of Zora Neale Hurston and others in the 1930s around the state of Florida. Using a digital mapping interface, you can actually follow these journeys, click, listen to the music, listen to the interviews, see the photographs, and get a sense of what it was like to move around Florida, virtually.”

J. Michael Francis, professor of history at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, specializes in Spanish colonial history. He has helped to develop La Florida Digital Interactive Archive.

“This is simply a different method of delivery of content,” says Francis. “We hope to drive an audience that might not pick up a book about colonial Florida, but might be willing to engage with a website. Might be willing to watch a video and then start to pose questions and maybe dig a little deeper. We would like to have all students have access to this material.”

Students at Rollins College, under the direction of history professor Julian Chambliss, have engaged in a variety of digital history projects. Perhaps most notable is the online reconstruction of an African American newspaper called the Winter Park Advocate, which was believed to have been lost. Chambliss and his students found two complete issues of the paper in local archives, as well as scrapbooks of articles from the paper to create a new digital resource.

“Increasingly in my classes we work on creating,” says Chambliss. “What can we create and distill from our interpretation of the primary sources. So we might make posters, we might do audio documentaries, we might try to reconstitute something that’s in fragments, digitally. All those are opportunities for the students to synthesize the information, and it’s like a proof of learning, a proof of concept, that they understand what these primary sources represent in the broader historical narrative.”

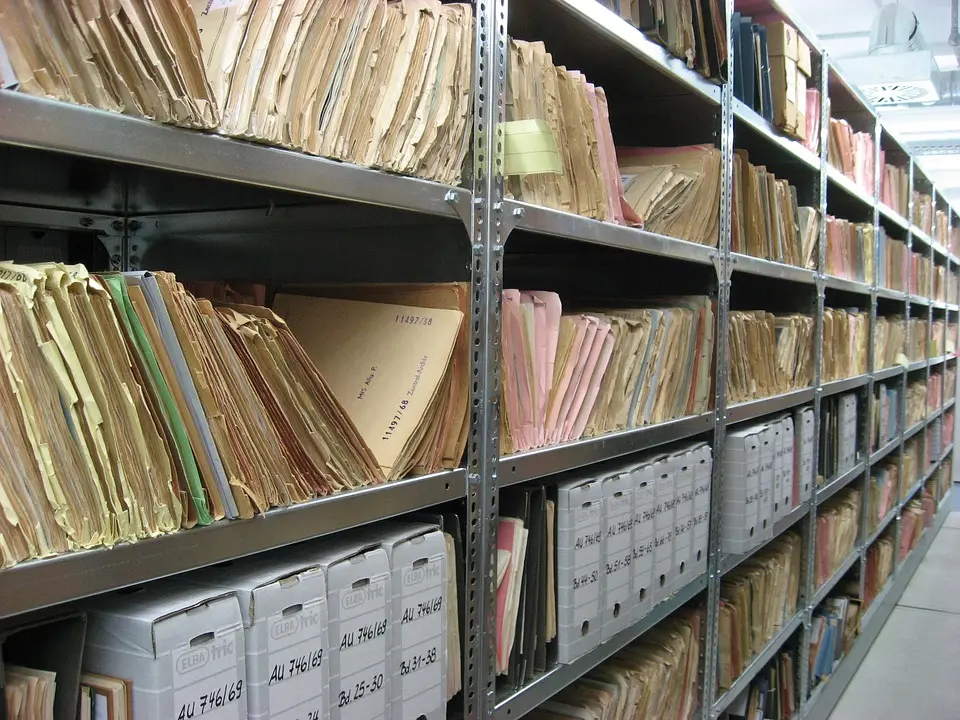

Traditional historical research involves physically going to libraries and archives to crack open old books, and wade through archival boxes of primary source documents. It can be a thrilling tactile experience. Digital historians say that’s not going away.

“For one thing, everything hasn’t been digitized,” says Connie Lester. “There is something about seeing the document, about holding it in your hand that is awe inspiring.”