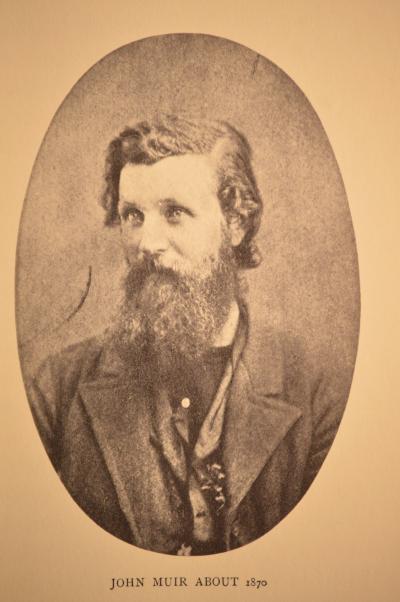

Sierra Club founder John Muir (1838-1914) is considered one of America’s most influential conservationists and naturalists. He is most famous for his works and writings in California and the Pacific Northwest in the last decades of his life; inspiring President Theodore Roosevelt's innovative conservation programs, including establishing the first National Monuments by Presidential Proclamation, and Yosemite National Park by congressional action.

But, even his official biography by the Sierra Club notes: “Perhaps his greatest legacy is not even wilderness preservation or national parks as such, but his teaching us the essential characteristic of the science of ecology, the interrelatedness of all living things. He summed it up nicely: "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe."

That brings us to his 1867 travels in Florida, and the observations of nature he recorded in his diary, found in a 1916 edition at the Library of Florida History. The entries show the beginning of his awareness of the inter-relatedness of all creatures and foreshadow the thoughtful writing style that became his hallmark.

We pick up Muir’s story in March, 1867, in a dark hospital room in Indianapolis where he is recovering from a serious industrial accident that nearly cost him his sight (an awl had pierced his right eye, and both eyes went blind). He resolved if he recovered his sight, he would not return to factory work, but would instead travel the world observing the wonders of nature.

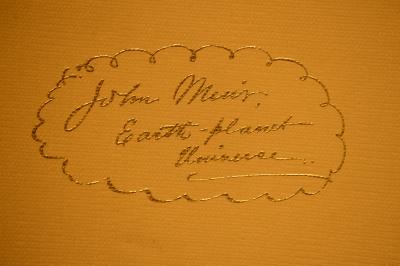

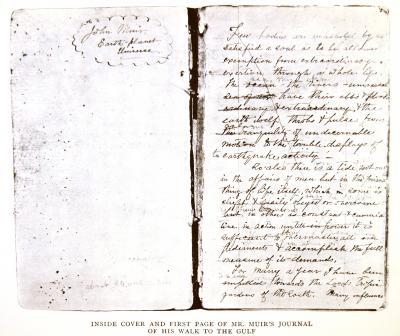

By September he had recovered and true to his word he set out on what he called his “1000 mile walk to the Gulf”, carrying a diary with a simple inscription,

“John Muir, Earth, planet, Universe”, a plant press, a couple of books and a change of underwear in a rubber bag. It was going to be an adventure.

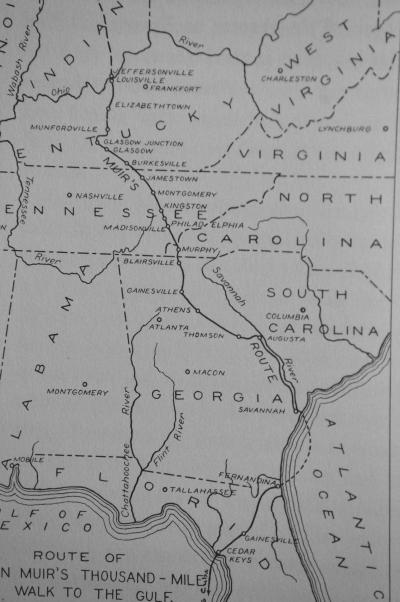

His plan, he wrote, was “simply to push on in a general southward direction by the wildest, leafiest, and least trodden way I could find, promising the greatest extent of virgin forest.”

It should be noted this plan would take him, a Yankee (well, born in Scotland but his family settled in Wisconsin), through the former confederate states, in the period of Reconstruction after the Civil War. His destination, Florida, had experienced economic devastation, was under Federal administration and had no constitution, was not even back in the Union yet. Former slaves and former confederate soldiers were moving into the territory, to get away from the even worse devastation and economic disruption in the states to the north. Tensions could be expected to be high.

He did not seem worried as he began his walk, and his journal.

By October 15 Muir was able to write “Today, at last, I reached Florida, the so called land of flowers that I had so long waited for, wondering if, after all, my longings and prayers would be in vain and if I should die without a glimpse of the flowery Canaan. But, here it is at a distance of a few yards, a flat, watery, reedy coast with clumps of mangroves and forests of moss drenched strange trees appearing low in the distance.”

That is how Fernandina appeared to a young naturalist and environmental scientist arriving by boat in 1867. He landed there because before the war the longest railroad in the state, the Florida Railroad, had been completed from there to Cedar Key on the Gulf coast. He was going to follow the railroad’s route across the peninsula. This meant sleeping in swamps, oak forests and pine forests, on the ground. It would mean seeing a lot of nature, up close and personal. It would mean he gained a real insight into how nature worked; how everything was interrelated.

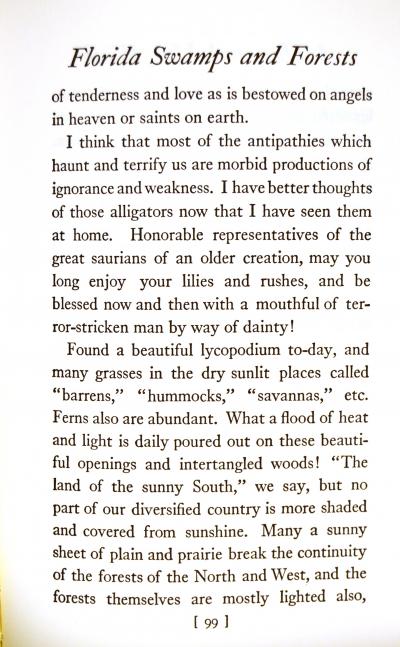

After meeting up with alligators and observing them he was able to write: “I think most of the antipathies which haunt and terrify us are morbid productions of ignorance and weakness. I have better thoughts of those alligators now that I’ve seen them at home. Honorable representatives of great saurians of an older creation, may you long enjoy your lilies and rushes, and be blessed now and then with a mouthful of terror-stricken man by way of dainty”.

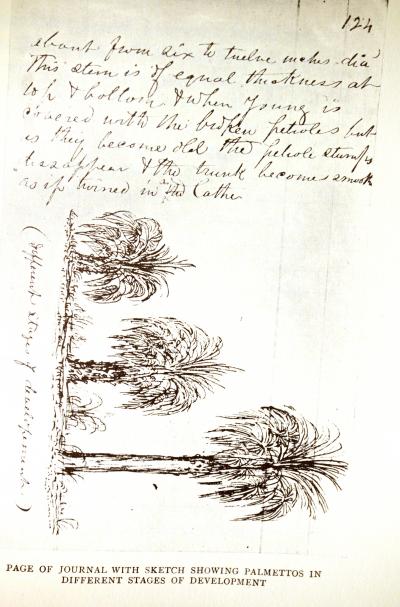

As he crossed the state, following the line of the rail road, he visited Gainesville, which he described as “an oasis in the forest”, and stayed for a while with a former Confederate officer, whom he described as friendly and genial despite Muir’s Yankee connections. While spending a few days hunting, he visited a palm hammock just west of town, “What a landscape. Only palms as far as the eyes could reach, smooth pillars rising from the grass, each capped with a sphere of leaves shinning in the sun as bright as a star.” The start of the writing style he became famous for later in life.

Muir reached Cedar Key, and as happy as he was to again smell salt air, the area almost killed him. He came down with malaria, and stayed for several months with a local family, the Hodgkins, before he was well enough to leave Florida.

He went to Cuba, abandoned a planned trip through the Caribbean and South America and went to New York, instead. From there he went to California, and into the history books.

It was not until 1898 that he returned to Florida. He went down the East Coast to Key West, then back through the center of the state through Palatka and Cedar Key. He met up with some of the surviving Hodgkins family and wrote fondly of returning to his old haunts.

By then state was bustling and growing , the railroads were back and it was a very different place. Muir could no longer see the Florida he saw. But, even now, in Yulee, Nassau County, in the John Muir Ecological Park, [http://floridahikes.com/john-muir-ecological-park]

Along the old right of way of the Florida Railroad, you can catch a glimpse of what John Muir saw in 1867.