The coquina walls of the Bulow Plantation stand in ruins, and only the foundation of the Mala Compra Plantation remains. Both ruins are remnants from early nineteenth century Florida.

The 150 acre Bulow Plantation Ruins State Park is located three miles west of Flagler Beach. Mala Compra is on North Oceanshore Boulevard in Palm Coast.

In 1821, Charles W. Bulow purchased nearly 5,000 acres of land in what is now Flagler County.

“The Bulow Plantation was one of the largest plantation enterprises in territorial Florida,” says Al Hadeed, local historian and Flagler County attorney. “It was very successful because its major crop was sugar. Sugar was very, very expensive and very prized. Sugar was also used to make rum, so it had a lot of different uses. He was very successful, but unfortunately, that success suffered the fate of the Seminole Indian Wars. His plantation, like many of the others in northeast Florida, was burned by the Seminoles.”

Charles Bulow died in 1823, and his 17 year-old son John Bulow inherited the plantation. He managed an operation that grew indigo, cotton, and rice, as well as sugar cane. Bulow coexisted peacefully with the Seminole Indians, and engaged in trade with them. When the Seminole burned the Bulow Plantation in 1836, it was not an attack on Bulow, but was retaliation against the U.S. federal government.

“When the federal troops came in to fight the Seminoles, Andrew Jackson’s idea was he wanted to ship them all west, get all the Seminoles out of Florida” says Hadeed. “The Seminoles adopted a strategy that wherever the federal troops went, they would burn those places so they couldn’t use them again.”

Bulow had such a good relationship with the Seminole that when federal troops attacked, Bulow tried to defend his Indian neighbors.

“He fired a cannon at the Florida militia because he was not happy with what they were doing, and ended up getting arrested and held in his own house, and they used his plantation as a fort,” says community historian Carl Laundrie. “When they decided that it was too dangerous for them to stay there, they removed him back to St. Augustine, and he was under house arrest. He saw a big red glow in the sky, and that was when the Seminoles burned Bulow Plantation.”

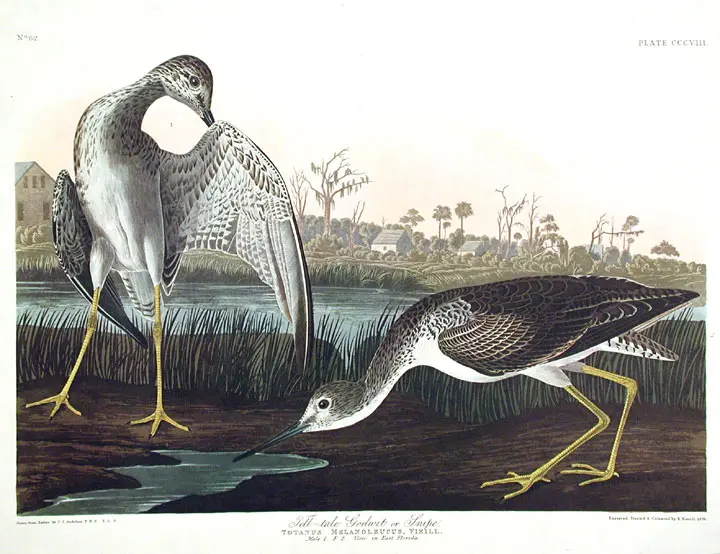

In happier times, Bulow hosted a famous visitor. Ornithologist, naturalist, and painter John James Audubon was a guest at the Bulow Plantation from Christmas of 1831 into January of 1832. The Audubon painting of the Greater Yellowlegs included in his “Birds of America” collection depicts Bulow Plantation buildings in the background.

“He had stopped at the Hernandez Plantation, but Audubon and Hernandez didn’t get along so well,” says Laundrie. “On Christmas day (1831), they struck out from Hernandez Plantation and went to visit John Bulow. John James Audubon and his entire entourage walked about 12 or 15 miles to Bulow’s Plantation. Bulow and Audubon became drinking buddies, they had a grand time.”

In 1816, Joseph Hernandez was given a Spanish Land Grant to establish the Mala Compra Plantation. Others who preceded Hernandez had not been successful on the property, which is why it was called Mala Compra or “bad purchase” in Spanish. Hernandez proved that name to be inaccurate, successfully cultivating the land.

When Florida became a United States Territory in 1821, Hernandez was the first Spanish representative in the U.S. Congress, and helped to have Tallahassee named the state capital.

The Mala Compra Plantation was also destroyed during the Second Seminole War.

The Mala Compra Plantation Ruins were first excavated by archaeologists in 1999. The exposed ruins include the foundations of coquina buildings and a well. A covered boardwalk allows visitors to explore the ruins.

“For a number of years there was a trailer park there,” says Laundrie. “The county bought Bing’s Landing, and then they discovered the site. They’ve done several archaeological projects there. They’ve built a big roof over it, and there are interpretive panels there today, so it’s a point of interest. People stop and look. It’s also a busy park. There’s a restaurant there, a boat launch, and people come down there to fish. It’s a combination of history and recreation.”