The land that the Spanish called La Florida encompassed the entire region that is now the southeastern United States. While several conquistadors had visited Florida prior to 1539, none were more intrepid explorers than Hernando de Soto.

“De Soto is an interesting character,” says Ben DiBiase, director of educational resources for the Florida Historical Society and archivist at the Library of Florida History in Cocoa. “He gained some notoriety serving with Pizarro in the Central and South American campaigns. He had spent some time in Peru, and became known for his somewhat brutal tactics when dealing with the native populations. He traveled back to Spain in the mid-1530s, and was given permission and a governorship to conquer the lands of what they then referred to as La Florida.”

Inspired by previous expeditions to Florida, including those by Juan Ponce de León and Pánfilo Narváez, de Soto prepared to establish a colony as his predecessors had failed to do. He recruited 620 volunteers to accompany him on a four year mission to search for gold and establish a settlement. Also aboard de Soto’s fleet of nine ships were 500 animals, including horses, cows, and pigs.

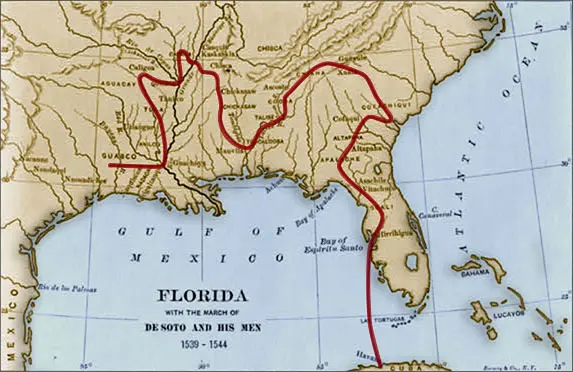

“In May of 1539, they landed somewhere near present day Tampa Bay, maybe a little further south, scholars disagree about the exact location, but what’s different from other expeditions is that they immediately started heading into the interior of Florida,” says DiBiase. “In fact, they actually headed north. There’s an archaeological site that was discovered in the 1980s, near present day Tallahassee, that confirms an encampment that they date back to the de Soto expedition.”

De Soto and his men traveled through present day Alabama and Georgia, as far north as Tennessee, across the Mississippi River, into Arkansas, and down into Texas. They were the first Europeans to encounter many of the native people of North America.

Three years into his four year expedition, de Soto contracted a fatal fever, without finding gold or establishing a colony.

“He died in May of 1542,” says DiBiase. “His burial plot is somewhere on the western edge of the Mississippi River. The few survivors, which at that time numbered somewhere between 300 and 350, decided to abandon the expedition and headed back down the Mississippi River, eventually making it to a Spanish colony in Mexico.”

There are four early written accounts of de Soto’s travels in La Florida. The first, published in 1557, was written by a member of the expedition known only as “the Gentleman of Elvas.” Luys Hernández de Biedma was with the expedition and wrote a report for the King of Spain that was filed in 1544, but not published until 1851. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, who died in 1557, wrote a history of the expedition based upon the lost diary of de Soto’s secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel.

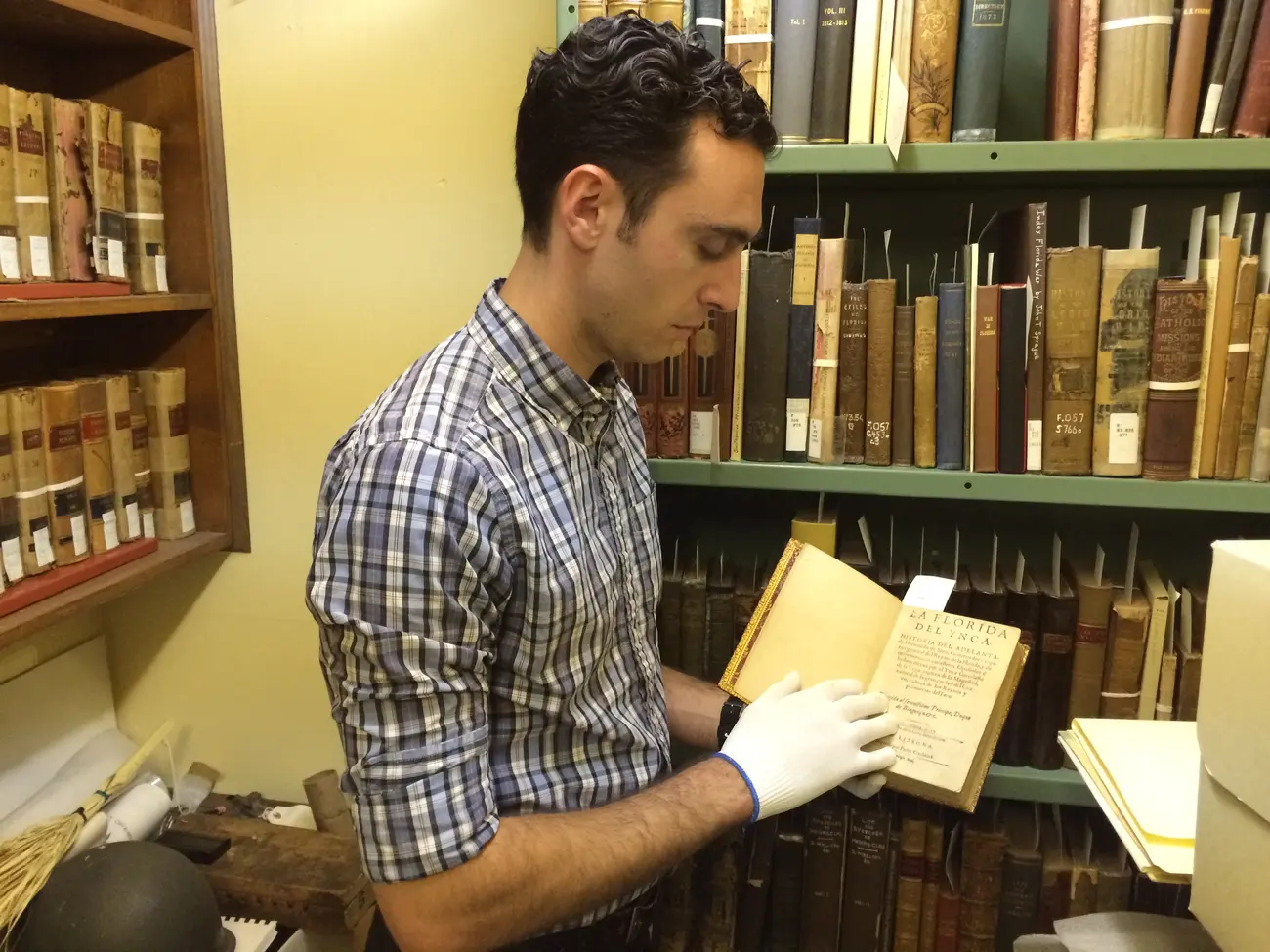

The fourth narrative describing the de Soto expedition was written by Garcilaso de la Vega. Published in 1605, the English translation of the title is “The Florida of the Inca.”

“De la Vega, known later in his life as El Inca or ‘the Inca,’ was culturally unique,” says DiBiase. “He was the son of a Spanish captain and an Incan princess. So he was descended from these noble families from both the European culture and the native Amerindian culture in present day Peru.”

“El Inca” based his narrative on oral history interviews conducted with an expedition survivor in Peru, and his research of historical documents in Spain. While the account does contain some historical inaccuracies, it is noteworthy for the author’s unique perspective on the interactions between the Spanish and the native people of North America.

The Library of Florida History archive contains an original, Spanish language, first edition copy of the 1605 book, carefully stored in a walk-in safe.

“When the Florida Historical Society reincorporated in 1905, and they formed a research library, the first donation to the library was this book, ‘La Florida del Ynca,’ and it was owned by non-other than Henry Flagler, the railroad magnate who was famous for building the Florida East Coast Railroad and developing Florida’s infrastructure,” says DiBiase. “This was his personal copy that he donated to the Florida Historical Society over a century ago.”