For a taste of old Florida, and of local shrimp and crab, consider Cedar Key, an island getaway in the Gulf described in a July, 2018 Miami Herald story as “...where the pace is so slow the tide may not even bother coming in.” It is a collection of small islands near the southern end of what might be considered the ‘Big Bend’ area. It is fairly quiet now, but those islands have a long history. In fact, as several holdings at the Library of Florida History attest, Cedar Key ‘coudda been a contender.’

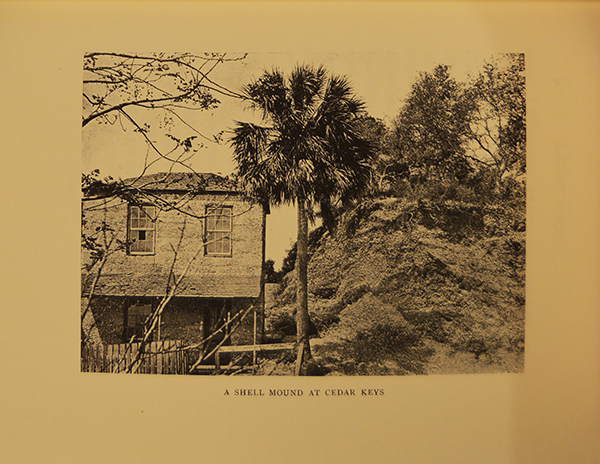

Human habitation on the islands dates back thousands of years, as several archaeological sites demonstrate (https://www.visitflorida.com/en-us/listing.a0t40000007quxUAAQ.html).

One of those sites was documented in a 1916 book found in the Library archives.

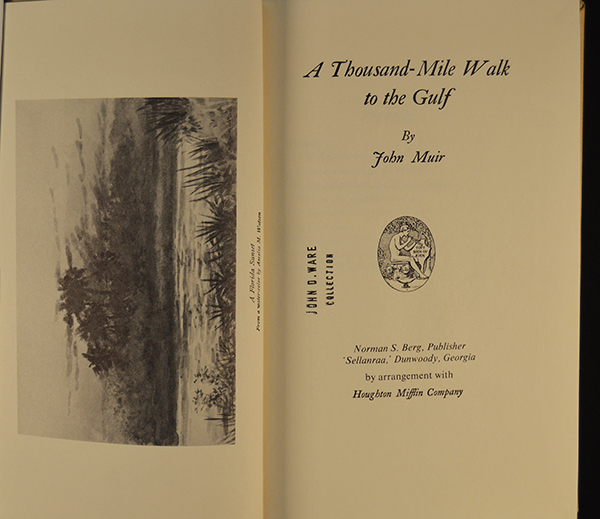

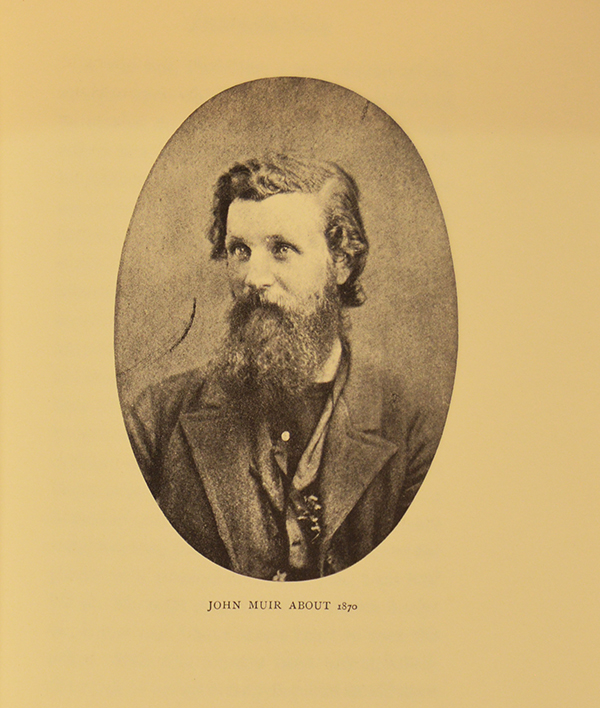

Yes, that John Muir (1836-1914) (https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/about/default.aspx)

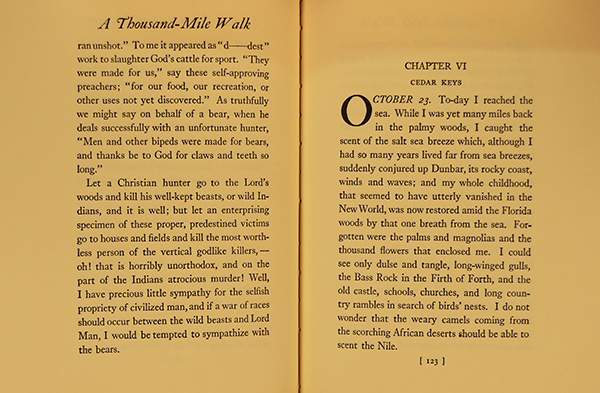

Long before his more famous travels in the western United States, he largely formulated his vision of nature on a long hike from Indianapolis that ultimately brought him to Cedar Key in 1867.

Somehow it seems from the first page of the chapter on his arrival in Cedar Key that even then the island could evoke an earlier time. By the time Muir arrived, the island had quite a bit of post-European contact history on the books.

The islands show up on Spanish maps as early as the mid and late 1500s and slowly developed as a port through the Spanish period.

Cedar Key was well enough established as a port that Maryland-born loyalist, officer and adventurer, not to say pirate and would be king, William Augustus Bowles (1763-1805), also known as “Estajoca” and “Billy Bowlegs” used it as a base of operations when he tried to set up an independent Native American government in 1795 (https://www.twoeggfla.com/billybowlegs.html).

Although the independence project did not go well, the island’s suitability as a smugglers’ den was established well enough that a couple of British citizens set up there during the Second Seminole War to help Native Americans smuggle in supplies to fight the Americans. Eventually, as statehood took hold, a legal and profitable alternative took hold - wood for pencils.

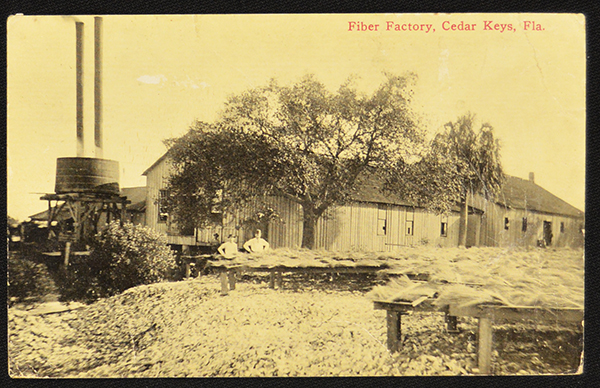

The Eastern Red Cedar trees that grew along the Gulf coast were perfect for them and eventually several mills such as this one pictured on a post card in the LFH collection were located on the island. It was a major port town by any measure from the 1850s on. Enough so that it was offered another shot at the big time as a destination, this time for a new technology, trains, specifically the Florida Railroad (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florida_Railroad).

Courtesy Florida Memory

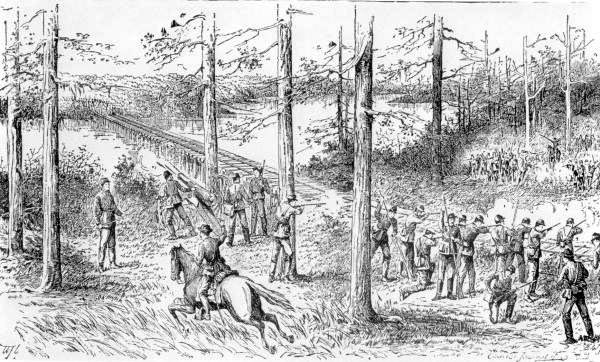

In the works for almost 20 years, the line to Cedar Key from Fernandina in northeast Florida would be a major link in the trade routes from the Midwest to the East Coast. With the placement of the last ties and rails, Cedar Key was ready for the big time. But as the first train crossed the bridge to Cedar Key, the calendar read ‘1860’. Not the best timing for a shipping enterprise.

Courtesy Florida Memory

The presence of the rail line did bring some excitement and some Yankees intent on enforcing the blockade of the Confederacy.

History teaches success delayed is not success denied and the period after the war was a success as measured by commercial activity and civic pride.

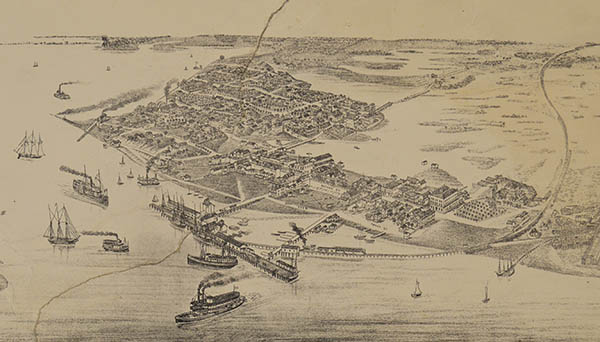

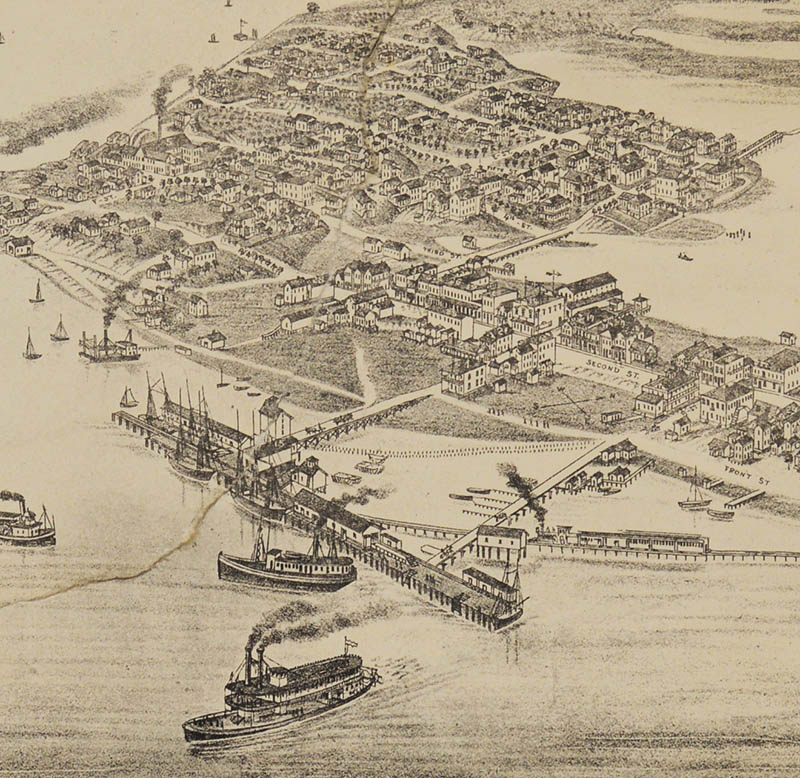

Which brings us to another Cedar Key holding in the Library of Florida History collection - this 1884 lithograph, a Panoramic Map or a “Birds Eye View” produced by the Milwaukee firm of Beck&Pauley.

Artists Adam Beck and Clemens J. Pauli were two of the country’s most active producers of these works of art, very popular in the pre-flight era. Most of their work was centered in the Midwest, but they had clients in at least 30 states and earned a spot at the Library of Congress worth a visit: https://www.loc.gov/collections/panoramic-maps/?fa=contributor:beck+%26+pauli.

More flexible than, say, a photograph from a balloon (certainly pushing the limits of the technology of the time,) these views could show an idealized vision of the community, bustling with ships and trains and factories.

A close-up looks reveals details of how the town was laid out and how the industry worked. This is information of use to historians and archaeologists today.

So, what happened?

Well, just a couple years after this Bird’s Eye View was created, Henry Plant completed his railroad to Punta Gorda, bypassing Cedar Key and eventually serving the deeper water ports in Tampa.

Then, in the 1890s the all too familiar coup de grace to many Florida plans, a hurricane which swept over the island, destroying almost all the buildings.

Courtesy Florida Memory

A fishing industry did take hold for a while, but by the 1940s the area was basically fished out.

Now, with fewer than a thousand residents, Cedar Key quietly protects its past. The whole town is officially registered as a Historic District and the Historical Society (https://cedarkeyhistory.org/), with a membership that recently went over 300, is embarking on a project to digitize its holdings for the first time ever.