Courtesy Florida Memory

Some current events are leading to a reexamination of our attitudes toward historical figures and the way our history has been presented. Two items in the collection of the Library of Florida History, featured in an extended presentation by Archivist Ben Dibiase (https://myfloridahistory.org/frontiers/radio/program/390) in the Florida Frontiers Radio show, could serve as object lessons about European Americans writing, even with all good intentions, about Native Americans.

Courtesy Florida Memory

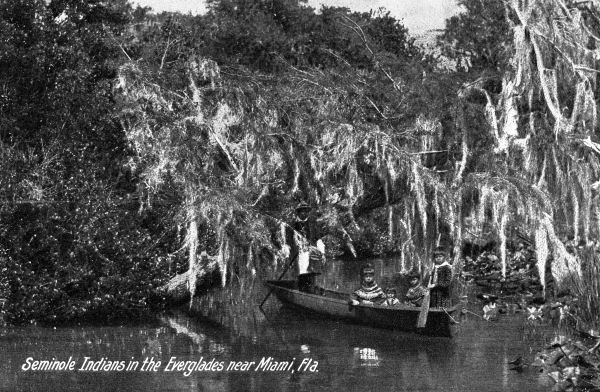

The Native Americans in these cases were the Seminoles - the few hundred surviving descendants of the thousands from several tribes which occupied the Southeast of what is now the United States and made it through the forced immigration to Oklahoma, known as “The Trail of Tears”, and the three Seminole Wars that were waged in Florida before the Civil War.

By the late 1800’s they were living in self-imposed isolation in the Everglades, eking out a living and understandably in no hurry to interact with the white settlers who were flocking to the coastal areas of Florida.

Courtesy Florida Memory

What contact there was between cultures was mainly limited to occasional visits at riverside trading posts, such as the one in Miami, pictured in 1901, and

Courtesy Florida Memory

the still-surviving Stranahan outpost (https://stranahanhouse.org/) in Fort Lauderdale, pictured in 1920.

There are some photographs of the Seminoles from the era, such as the 1900 (top) and 1910 images above. It must be remembered they were composed by white photographers shooting pictures to sell to a tourist crowd. It is likely they bear the same relationship to real life as the stiff, not to say grim, photos of any European American ancestors from that age.

This is not to say everything written at that time is fiction. This was a time of what is now dubbed “the Progressive movement” (https://www.britannica.com/place/United-States/The-Progressive-era) when a lot of thoughtful and concerned people were genuinely delving into what they saw as the wrongs of the nation and the mistreatment of what we might now call ‘others’. In fact, that trading post in Fort Lauderdale has a connection to one of the samples in the Library of Florida History collection.

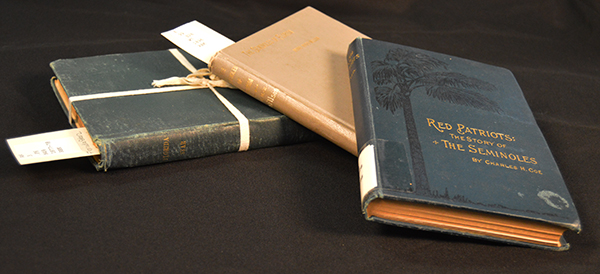

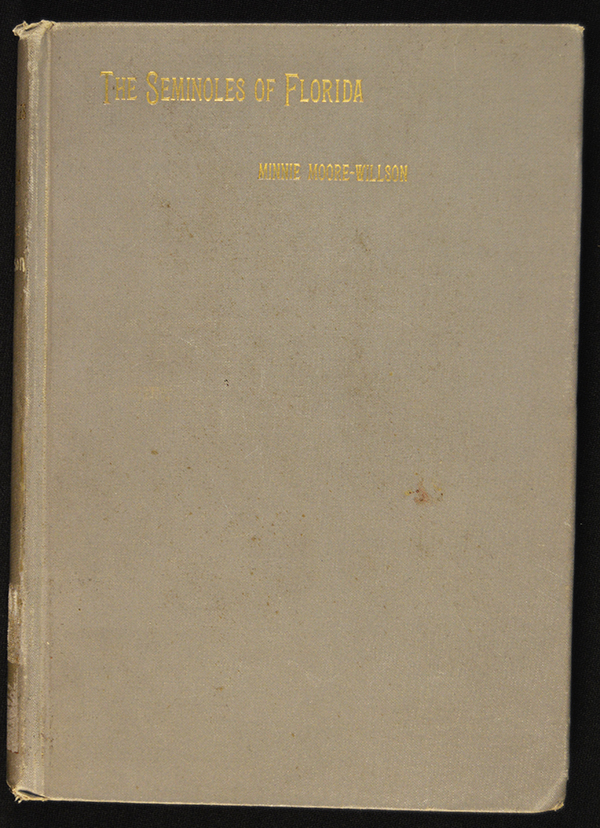

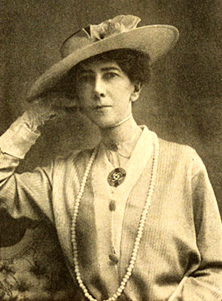

The sample is this 1896 anthropological work, The Seminoles of Florida, by Minnie Moore-Willson (1859-1937), a Pennsylvania native who developed an interest in the Seminoles while visiting Florida in the early 1880’s.

Minnie Moore-Willson’s interest in the Seminoles, and many things Floridian, (https://atom.library.miami.edu/asm0203) was not transitory. She and her husband, James, built many relationships, with the tribes and with Florida’s social and political leaders, over the decades.

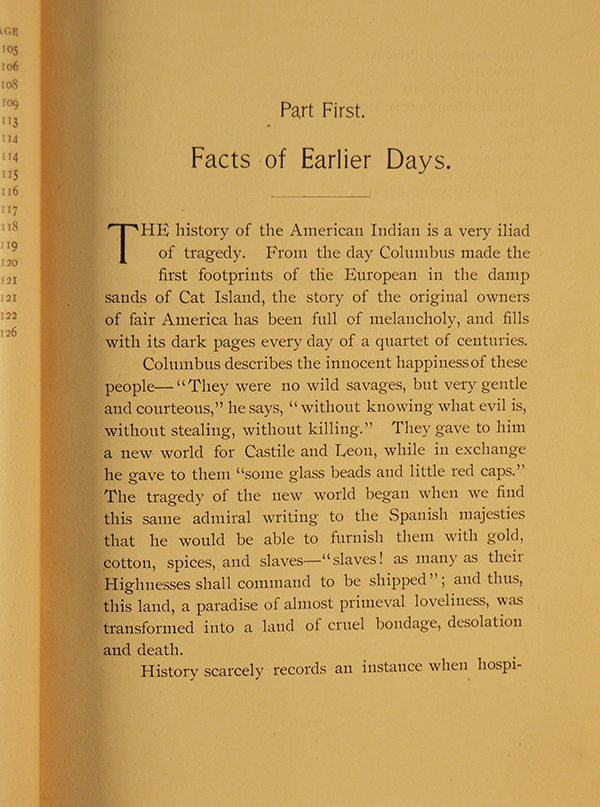

From the first words of the book it is easy to see where their sympathies lay. We can surmise the impact this would have had on many white Americans, raised on stories of brave Indian fighters overcoming treacherous savages.

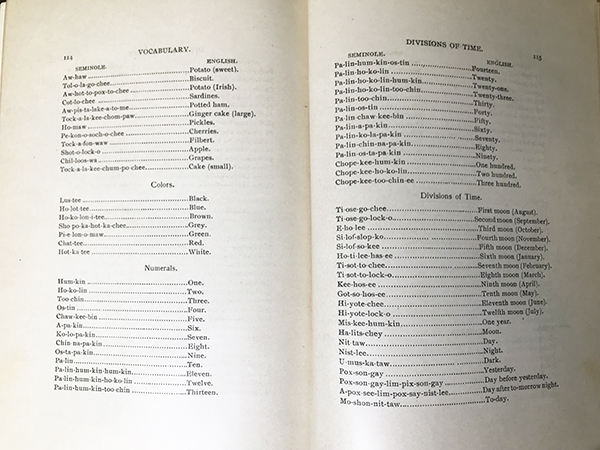

The book is not simply a collection of stories. Vocabulary lists (credited to Mr. Moore-Wilson) testify to the extent of firsthand knowledge the couple had amassed over the decades. This brings us back to the Fort Lauderdale trading post.

It turns out the lady of the trading post turned residence household, Ivy Julia Cromartie Stranahan (1881 – 1971), was a fellow activist and cohort of Moore-Willson and clearly facilitated much of the contact with the Seminoles which informed her book (https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4739/).

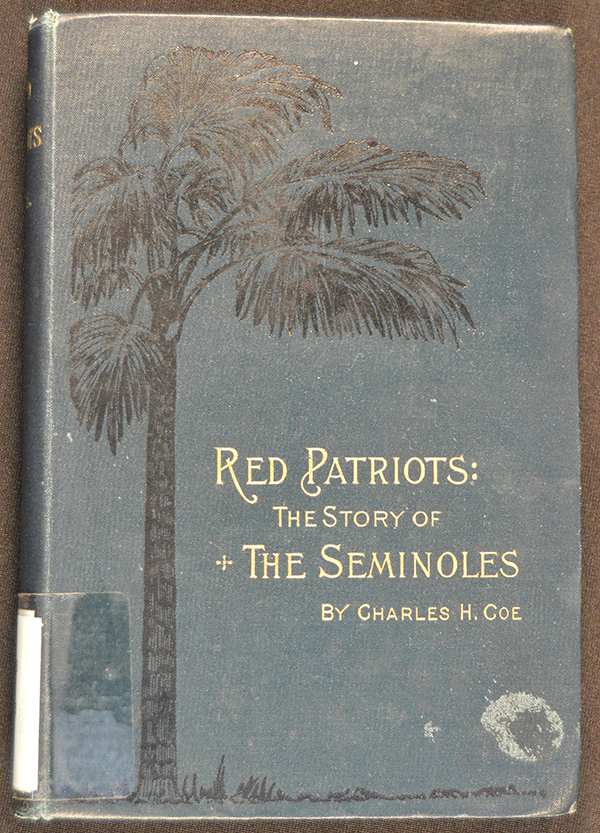

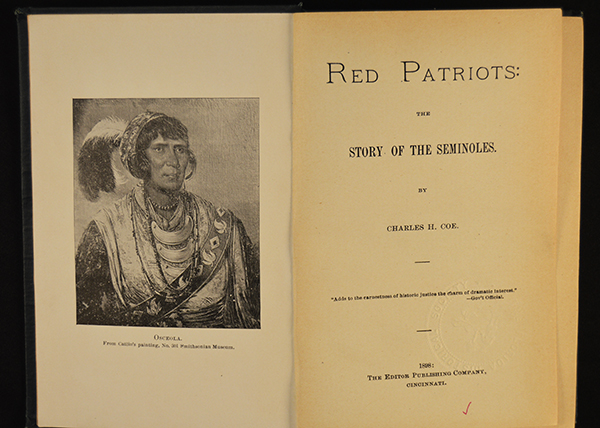

Another holding at the library is similar in tone, but appears based more on what scholars call ‘secondary sources’ - in this case, likely things white folks wrote about the Seminoles.

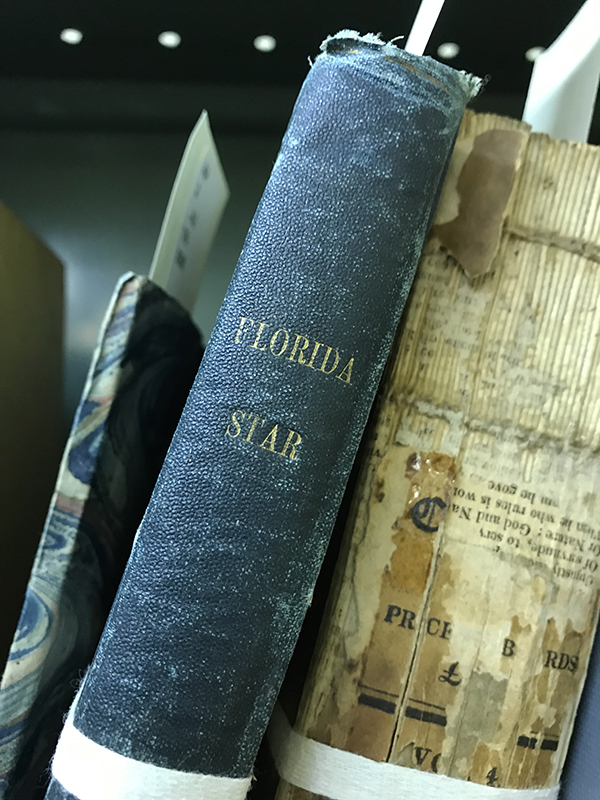

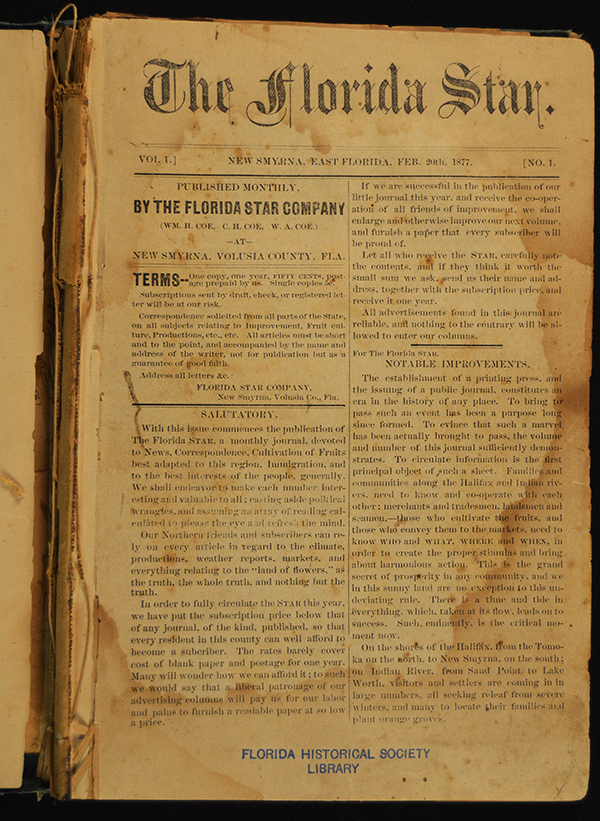

The author, Charles Henry Coe (1856-1954), spent several years beginning in the 1870s living along the East Coast of Florida and exploring the waterways on board his boat, the Buccaneer. Originally from Connecticut, he made his living for the most part by printing.

This actually resulted in another item from him in the Library of Florida History collection, reprints of his monthly newspaper, The Florida Star.

But for all his travels and reporting, there is no evidence he ever actually met the Seminoles during his stay in Florida, and by 1898 when he published Red Patriots: The Story of the Seminoles, he was apparently between jobs at the Government Printing Office in Washington, D.C. He and his family are remembered, however, along the East Coast: https://www.jupiter.fl.us/DocumentCenter/View/4060/Timeline-of-Henry-Charles-Coe?bidId=

From the opening pages it is clear Coe intends to tell their story to a progressive era readership,

or, more accurately, a specific kind of acceptable progressive era readership.

Targeted or not, Red Patriots was not a commercial success at the time. It was an educational effort, and Coe was a strong advocate for giving the Seminoles land-owning rights in the area they live - good land, which, in the Everglades might be defined as ‘not under water.’ At a time when the state and developers were rushing to drain the swamp for agriculture and settlement, it was a hard sell.

But as we know, a ‘hard’ sell is not an ‘impossible’ sell. We know in part because of the one and a half million acre Everglades National Park (https://www.nps.gov/ever/index.htm) where, until recently, we could go to appreciate one of Florida’s great natural wonders. Incidentally, approaching the park from the east you will come to the Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center in Homestead, named for another Connecticut Coe who developed a love for Florida.

Courtesy Florida Memory

That would be Ernest “Tom” Coe (1866-1951), the man receiving the congratulatory plaque at the 1947 dedication of the park and no known relation to Charles. Ernest was a naturalist, a designer of gardens for the rich and famous, who liked to vacation in Florida and developed a passion for protecting the environment. He teamed up with other environmentally aware people, like Marjory Stoneman Douglas, to write and campaign for protections. It is said he was disappointed when the National Park was created on the southern tip of Florida; he had wanted it to include the whole peninsula.

Once the Seminoles would have wanted the same thing.

Now, at least, they can start to tell their own stories: https://tribe.miccosukee.com/, https://www.semtribe.com/STOF