In several recent segments we have mentioned the importance of surveying for Florida’s development (https://myfloridahistory.org/frontiers/radio/program/379, https://myfloridahistory.org/frontiers/radio/program/380 ). For this issue we return to the years before Florida was part of the United States and countries struggled to define just where Florida began and ended, anyway. This weathered and now fenced in stone, at latitude 31 just south of Bucks, Alabama, provided...and provides... part of the answer.

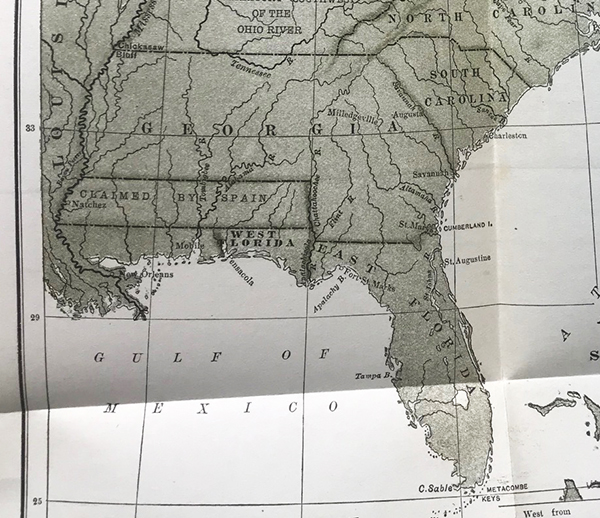

As the dust settled at the end of the American Revolution, Spain regained control of Florida (a consolation prize for not getting Gibraltar from the British) and settlers from the new state of Georgia wanted to claim homesteads in ‘the West’, an area we now call the Florida Panhandle and Alabama.

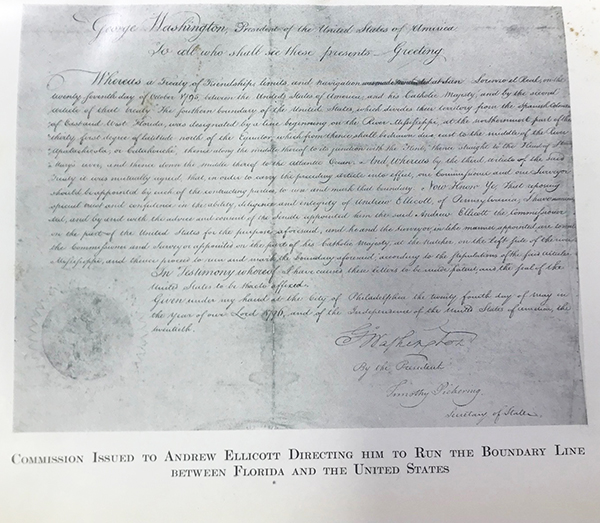

The 1795 Treaty of San Lorezo/Pickney’s Treaty (https://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/pickney-treaty ) between Spain and the United States set the 31st parallel as the U.S.-Florida border. That was all well and good to bewigged negotiators in Spain, but who were you going to call to translate lines on a map to lines in the sand?

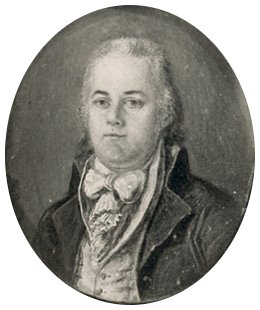

A surveyor, of course; but not just any surveyor. President George Washington wanted the best he could get to head up the joint American/Spanish expedition to the wilds of west Florida, and that turned out to be Andrew Ellicott (January 24, 1754 – August 28, 1820).

A Revolutionary War veteran originally from Pennsylvania who settled in Maryland after the war, this young man with an aptitude for engineering and mathematics had a knack for being associated with projects that earned a place in the history books. His first job of historic note was with a group resurveying part of the Mason-Dixon line. For the next, he was in charge of a group settling a border dispute between New York and Pennsylvania near Lake Erie. President Washington was duly impressed with the quality and honesty Ellicott exhibited in his work.

Impressed enough to appoint Ellicott to another gig we can observe today via caged rocks, first, laying out the District of Columbia and placing these stone to mark the corners and boundaries, and second, laying out the City of Washington itself.

So who better to send to the wilds of the frontier to deal with Spanish officials, Georgia settlers, Native Americans, free and runaway African-Americans, even French and British expats. When he arrived, via the Mississippi River in an area called Natchez (remember, the claims of the colonies then extended all the way to the river,) he found there were tens of thousands of people in that wilderness, all with different agendas. Putting lines in the sand would take a while.

From September of 1796 until 1800 in fact. Fortunately for posterity, Ellicott was an exhaustive note taker. The details of his adventures, from the arcane navigational details of his surveying to his personal relations with the hundreds of stake holders he had to deal with over those years all made it into his diary and a book he wrote in 1803.

In turn, his writings were published for a wider audience in 1908, and that volume in the collection of the Library of Florida History offers a detailed look at an individual whose expertise, honesty and respect for science and facts 200 years ago is making an impact today. The stone at the top, dated 1799, that once marked the edge of America and the domain of Charles IV of Spain now marks the line in the sand between Florida and Alabama.