Archaeology today is a tedious process. At sites such as this in Wakulla Springs, photographed as part of a future episode of Florida Frontiers TV, the scientists painstakingly note the exact position of every artifact and below-ground stain they find in the dirt.

The removed soil is sifted so nothing is missed. Even tiny bits of worked stone or pottery can tell a story of the indigenous people who inhabited Florida for hundreds, perhaps thousands of years before the Europeans arrived.

One can only wonder how much information has been lost by the destruction of huge shell mounds found all over Florida, some 50 to 70 feet high, big enough to be used as navigation markers by the early European navigators plying the waters off La Florida. The stories of generations, ground up to make roads and parking lots.

It wasn’t because the settlers and developers didn’t know the mounds were man-made. Those 15th and 16th century sailors knew what they referred to by the Dutch term “kjokkenmoddings’ were not natural. Written French and Spanish records from the time note the sailors said the mounds were manmade. In the 1830’s and 40’s, as settlers started pushing into Florida’s interior, folks noticed the mounds and knew they were tangible signs of occupation from before the arrival of Europeans.

But it was not until the late nineteenth century that the mounds received any scientific attention, and it was the early twentieth before real archaeological studies began.

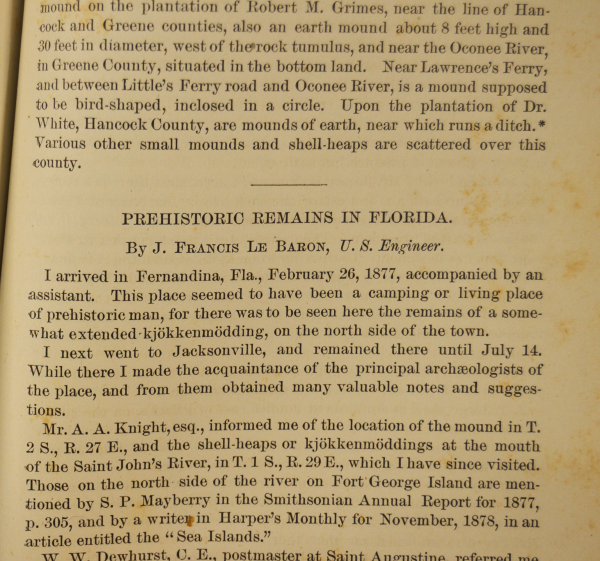

Some of that early scientific attention came from J. Francis LeBaron, (1847-1935) an engineer and cartographer with an eye for relics.

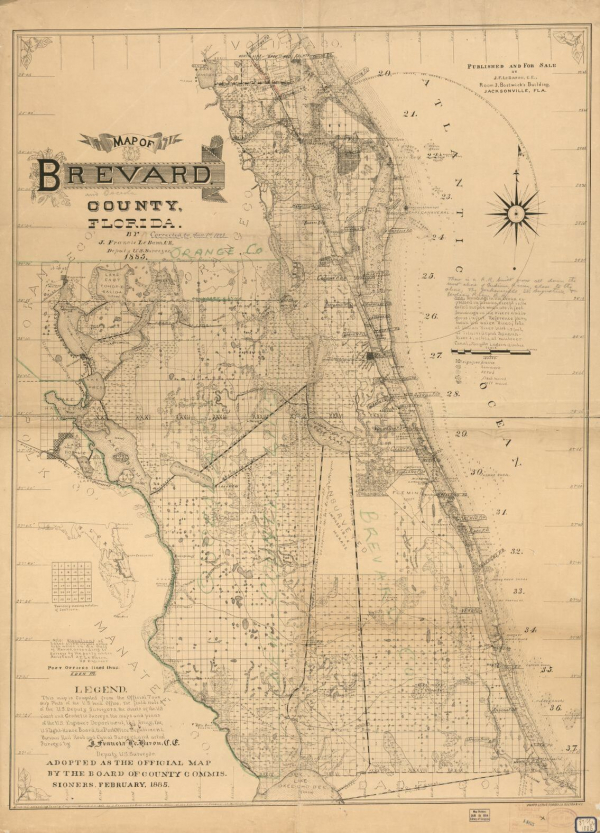

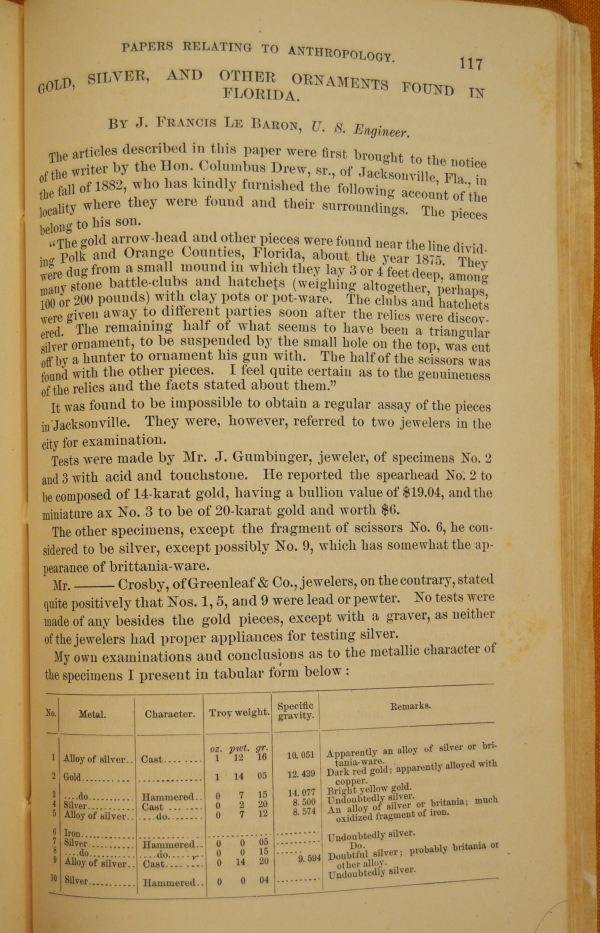

Today he is better known for his maps than archaeology. He did some private surveys, but his main job was coastal surveys of the state for the U.S. Government. His work took him all over the state for decades, and from the beginning he noted the shell mounds. He reported what he saw and found over the years to the Smithsonian Institution.

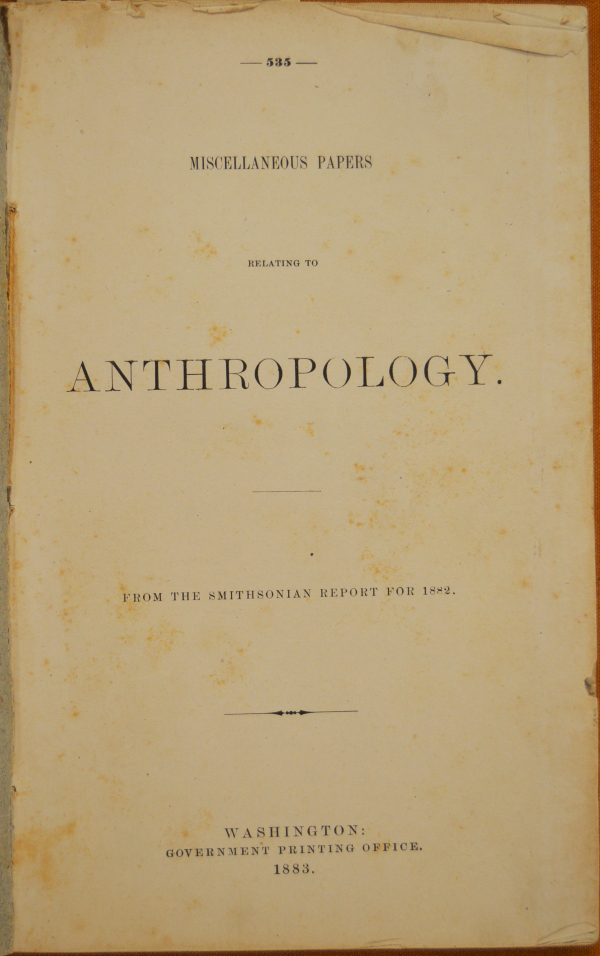

Some of his reports can be found in an 1883 Smithsonian publication in the collection of the Library of Florida History, “Miscellaneous Papers Relating to Anthropology.”

One paper relates to LeBaron’s arrival in Florida in 1877, and shows how he immediately developed an interest in the mounds he found there.

Over the years he refined his excavation technique and sent relics and increasingly detailed reports to the Smithsonian. He also made note of the destruction of the mounds. Early on he wrote about a mound just north of Palatka on the St. John’s River, “a shell mound about 12 feet high, the eastern edge abraded by the waters of the river into a steep bluff. A large part of the shell heap had been carried away by boats to form walks and driveways in Palatka, and for fertilizing purposes. This practice is very common throughout the state and is working the speedy destruction of these interesting remains.”

His information is still useful today. Before digging in the field, modern archaeologists have to dig into historic records to figure out what happened to the sites that have vanished.