Even by the not-so-warm-and-fuzzy standards of 16th Century Spanish soldiers, Hernando (Fernando) de Soto was not, in most contemporary accounts, a nice guy.

On the other hand, in an 1859 biography of the best known Spanish Conquistador, found in the Library of Florida History, the author says he does not read those early accounts as negative at all.

This sympathetic biography was unusual for the time, in fact for any time since de Soto’s death.

Author Lambert A. Wilmer, a journalist and writer in Philadelphia, used the same primary sources as everyone else. He simply says previous writers didn’t have it right; they just wanted to put their point of view across and he came up with a different, interesting and sympathetic take on de Soto.

Maybe it was just a desire to be a nice guy. Wilmer was a friend and supporter of Edgar Allen Poe for many years. In later years, Poe erroneously considered Wilmer to be a personal enemy after Wilmer had said to a mutual friend that he, Wilmer, was concerned about Poe’s drinking. Even after Poe’s death, Wilmer wrote several brief but friendly defenses of Poe.

Why Wilmer took on a comprehensive biography like this is not certain. Usually he stuck to poems and short stories. This clearly was his most ambitious work. It is also easy to see why it was such a shocker.

Let’s recap the life and times of Hernando de Soto. He was a native of the impoverished Extremadura region of southwestern Spain, born sometime between say 1496 and 1500 to a family of minor nobility and modest means. Like so many young Spanish men in his circumstances, his main opportunity was the military, and he felt the allure of The New World.

Still in his teens he got himself included on an expedition to the West Indies led by Pedro Arias Davila in 1514. For de Soto the dream worked, he earned a fortune from Davila’s conquest of Panama and Nicaragua, and by 1530 he was the leading slave trader and one of the richest men in Nicaragua. Things only got better when, in 1532, he joined Francisco Pizarro on gold hunting expeditions into Columbia and Peru.

Remember, these guys are called conquerors, not tourists, or traders.

With his amassed wealth, de Soto returned to Spain in 1536, married (the daughter of his old patron, Davila, in fact), built a comfortable home in Seville and began to look around for something else to conquer.

That something else turned out to be Florida, and what is now the southeastern United States. There had been several Spanish expeditions to the region, but they were considered failures. They didn’t produce gold.

Why a wealthy man already nearing 40 years of age in an era when average life expectancy was likely in the 30’s would want to leave home and battle Indians and disease in the swamps and forests of Florida is as big a mystery as why a poet would take on a biography of a slave trader and try to demonstrate he is really just a misunderstood businessman.

But, they both happened. In 1539 de Soto landed in Tampa Bay on ten ships and with about 600 soldiers began a well planned expedition up the Florida peninsula.

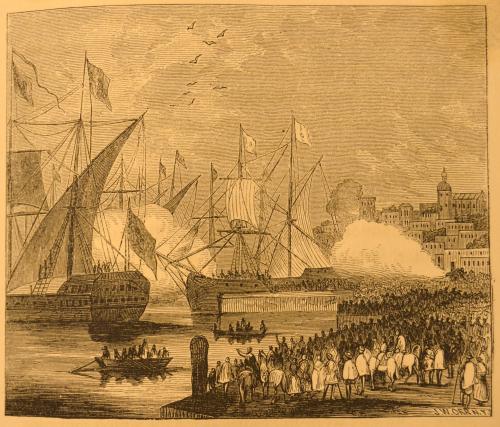

Wilmer’s book follows along, complete with romantic etchings of the fleet setting sail from Cuba (where Mrs. De Soto was to wait),

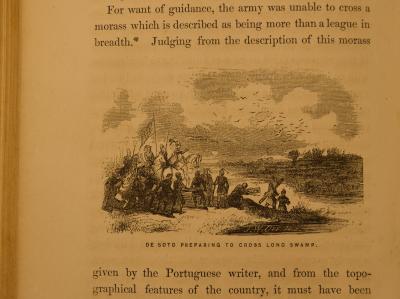

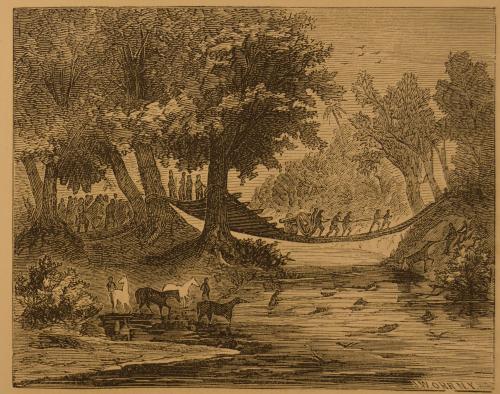

of the men coping with the Florida swamps,

and the Florida rivers.

What it does not show is the battles with the Indigenous People, or the chaining up and enslaving of any survivors the soldiers could capture.

For three years the expedition covered about 4000 miles through what is now the American South East, from Florida to the mouth of the Mississippi River. De Soto is credited with discovering it, and being the first European to cross it (an honor that may well belong to a nameless soldier who jumped out of a skiff to hold it while de Soto waded to the river bank). To this day the exact route de Soto took is in doubt, except for one place. We know they spent the winter, including Christmas, of 1539/40 at the Native American village of Anhaica Apalache, one of the principal villages of the Apalachee Nation. We call it Tallahassee.

State archaeologists have found the site, confirmed by contemporary documents and the uncovering of metal artifacts and trade beads. Only a few acres in size, de Soto State Park is within walking distance of the Capitol and is open daily for visitors.

Exactly where de Soto went after that is a mystery. It is recorded that he came down with a fever and died in Louisiana along the Mississippi River in May, 1542. His body was sunk in the river, and may remain under the silt to this day.

About half of his men survived to rejoin the ships to disperse through the Americas or return to Spain. Those who did get back to Spain soon began to write up unflattering accounts of de Soto and many of the other Conquistadors, lumping them together as brutes slaughtering the Native Americans and seeking gold at any cost. Add to that the impact of the “Columbian Exchange”, not only goods and ideas, but warfare and disease that devastated the native populations and it is easy to see how reputations were deservedly tarnished, and how an effort to rehabilitate them would be something of a stretch.

As detection technology improves it is possible more sites along the de Soto route will be discovered. This could lead to recovering more traces of lost indigenous life.