In an era when governments drop in and out of treaties and agreements the way children change BFFs, it might be worth it to take a moment to see bickering over the wording of international documents is not exactly a new phenomena. As an example, consider the international dispute over the border of West Florida in the early 18th century.

Basically, Spain controlled all of what is now Florida until the Treaty of Paris (1763) ended the Seven Year War, better known to Americans as “The French and Indian War.”

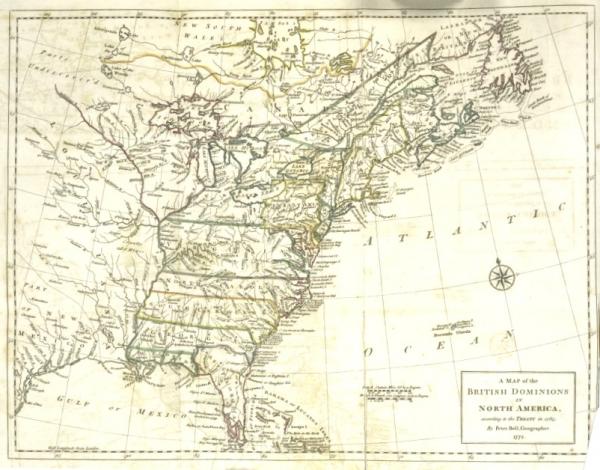

Britain was the big winner, and the treaty gave it control of Spanish Florida. On the map, Florida butts up against Spanish controlled New Mexico around about the Mississippi River. France still had interests along the river, what would eventually become the Louisiana Territory, and in a secret negotiation France had ceded control of all lands west of the Mississippi to Spain.

Frankly, at that moment and for a while, no one seemed to care exactly where the lines were drawn. No one lived there. Then, after 1783, the new United States became a player. It was back to Paris for another treaty when the British gave up on their rebellious American colonies. Spain had helped the Americans with the Battle of Pensacola, so they entitled to some spoils. The Spanish wanted Gibraltar, but the British said they would go back to war before giving up their position at the mouth of the Mediterranean. So Spain got Florida back as a consolation prize, ushering in the “Second Spanish Period.”

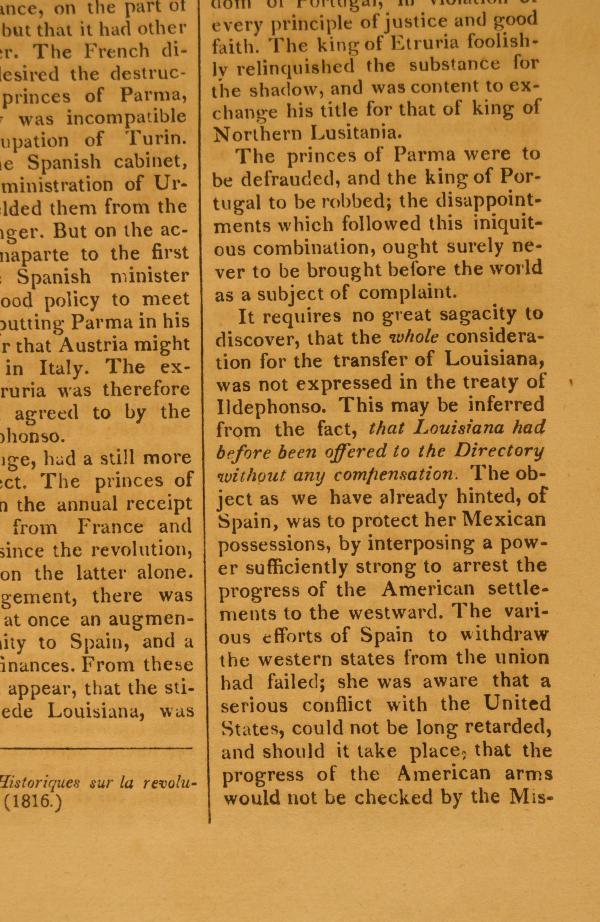

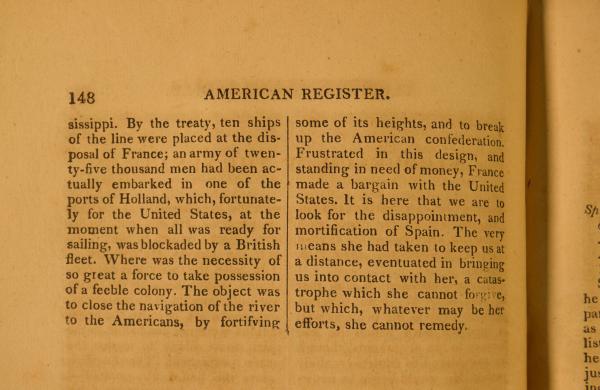

The French still had interests along the Mississippi, American settlers began pushing into the northern part of Florida and the areas that are now Alabama and Mississippi and Louisiana, Spaniards returned to La Florida, and the British, for the most part, left. In 1795 a treaty between Spain and the United States set the northern border of Florida at 33 degrees latitude and in 1800 Napoleon pressured the Spanish to give France back the lands drained by the Mississippi River. Spain gave in, with the understanding if France ever wanted to get rid of the land, it would come back to Spain.

The French sold it to the Americans; the “Louisiana Purchase of 1803.”

More and more Americans were moving in, the early stages of the American settlement of the west. We often think of “Manifest Destiny” as covered wagons crossing the Great Plains. The reality is it started in West Florida.

In September 1810 the American settlers had proclaimed “The West Florida Republic” after a brief firefight at Fort San Carlos at Baton Rouge, unfurling their new flag.

They didn’t need a more complicated flag. On December 10, 1810 an American military force took control of the area, and the Flag of the Republic of West Florida was lowered.

The settlers had actually taken over the local government of this region with fuzzy borders, a mix of loyalties and a history of international agreements that embodied the politicians and diplomats instinct to “kick the can down the road”, or perhaps “roll the butter churn down the path” when it came to touchy subjects. But now the Spanish technically controlled the area, and U.S. soldiers occupied it.

It came to be called “The West Florida Question.” It would be answered by interpreting the language of all those treaties, picking apart the words diplomats put on paper and the actions the various countries took on the ground. Who better to do that, filtered through the lens of American expansionism and Manifest Destiny, than a lawyer, congressman and judge from Pittsburg?

Henry Marie Brackenridge (1786–1871) had a varied career; writer, journalist, lawyer, judge, forester, spy, diplomat, Congressman, the list goes on. For this story we focus on the time he was Deputy Attorney General of the Territory of Orleans (Louisiana) and a district judge in the American territory next to West Florida.

In 1817 he turned his attention to “The West Florida Question”.

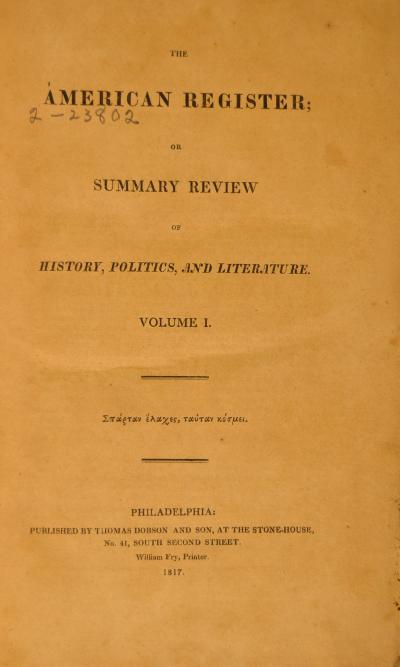

His article is found at the Library of Florida History in Volume 1 of The American Register, a book meant to be a serialized publication providing contemporary politics, arts and culture articles a la "The Atlantic," but there is no indication a Vol. II was ever printed.

In words that could be written by any lawyer any time, the builds his case and presents his conclusions in favor of his American clients.

Simply, West Florida should have been included in the Louisiana Purchase, Q.E.D.

In 1819 this resulted in the Onis-Adams Treaty, also called the Transcontinental Treaty giving Florida to the United States and setting the western borders of the Louisiana Purchase (at least for a while) and ending all Spanish claims in the Pacific Northwest. The United States recognized Spanish sovereignty over Texas (at least for a while).

When it was finally ratified in 1821 Florida became a U.S. Territory.

We can see a remnant of all this drama today. In Southeast Louisiana there are eight parishes (as they call counties): East Baton Rouge, East Feliciana, West Feliciana, Livingston, St. Helena, St. Tammany, Tangipahoa, and Washington, still called “The Florida Counties” because, once, they were.