The first European religion to come to Florida was Roman Catholicism. Virtually every Spanish expedition, bent on finding riches, included a priest, bent on spreading their version of Christianity and saving the souls of the natives.

The first Protestant version of Christianity to show up was the 1564 effort by the French Huguenots to establish Fort Caroline, probably near what is now Jacksonville, to create a ‘safe haven’ for their co- religionists. It did not go well. About one year later the Spanish returned and, to put it nicely, regained control of the area. In fact, they wiped out the heretics, set up St. Augustine and established what would prove to be two centuries of Spanish rule and Roman Catholic dominance.

Spain ceded Florida to Britain in the 1763 Treaty of Paris that ended the conflict known to Americans as “The French and Indian War.” Britain had agreed in the treaty to protect the rights of its new subjects to practice Catholicism, but that did not prevent the introduction of the Church of England to Floridians, likely numbering fewer than ten thousand. Most of the Spanish settlers left, and the Native Americans had largely been wiped out by European diseases and aggression.

The Church of England did try, building churches in St. Augustine and Pensacola (the big cities) and establishing parishes in some frontier outposts. The farthest south they got was New Smyrna in what is now Volusia County, but the effort failed.

Then, in 1783 the Spanish, and Catholicism, were back, much to the dismay of the British subjects who had remained loyal to the crown during the American Revolution (and the Loyalists who had relocated to Florida from the other colonies after the war, expecting to remain under British rule.) This time most of the British left.

American settlers started moving into what we would consider North Florida, then officially East Florida and West Florida. In 1821 the land was basically ceded to the United States. You could say it was traded for Texas, but that is another story.

With the Americans came the brands of Protestant beliefs that had flourished under the Constitution, in particular the version of Church of England known as Episcopalian. They set up a church in Tallahassee in 1824, had a presence in St. Augustine and Pensacola, tried to set up parishes throughout the sparsely settled interior and had a church in Key West by 1845.

The big growth in Florida, and in religions, came after the Civil war and, of course, World War II.

But even now you can see the echo of those early settler patterns in the organization of the Catholic dioceses around the state.

Various holdings at the Library of Florida History offer detailed information about the operation of the institutions as well as the mindsets of the practitioners.

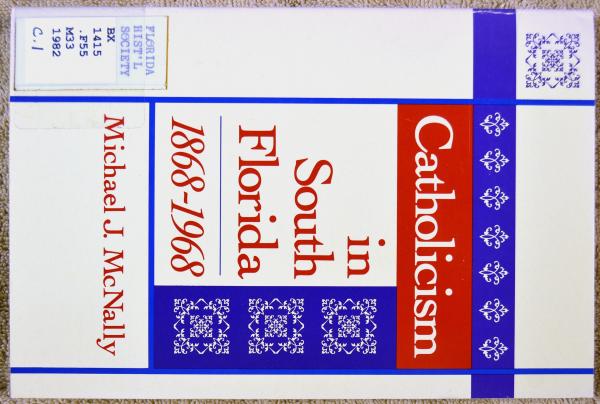

This 1923 history booklet offers the official overviews you would expect.

It also offers surprisingly fine-grained information about specific parishes and locals, and a lot of names of priests and laypersons, details of interest to genealogists as well as local historians.

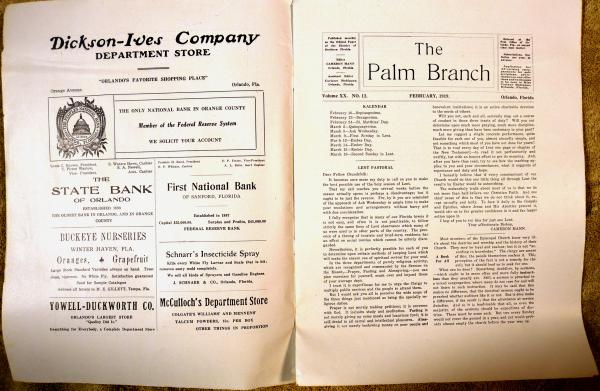

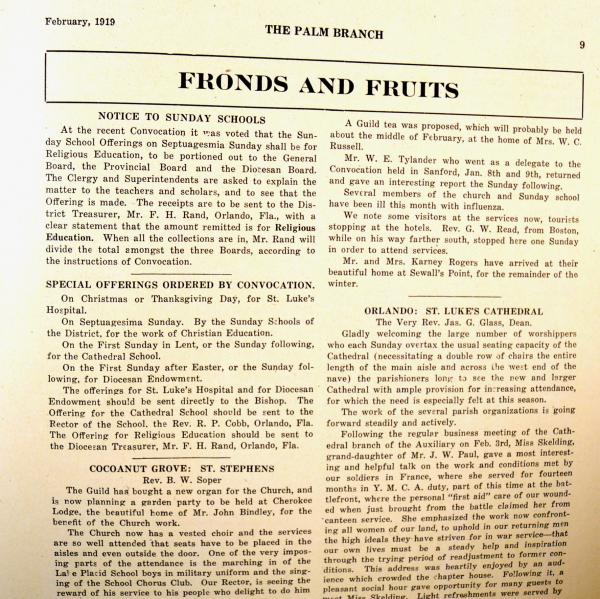

One holding of particular interest is the complete run, from 1915 to 1938 of the monthly newsletter of the Orlando based Episcopal Diocese of Southern Florida, The Palm Branch. The cover, sporting palm leaves and trees with symbolic ties to both Florida and Christianity, remained unchanged for the entire run.

Each issue naturally included religious information, church business, events calendars and articles on topics the Bishop wanted to discuss.

But a closer look shows the same fine-grained information about individuals and social conditions that is invaluable to genealogists (church records are a mainstay of family research) as well as local historians, scholars of the period and anyone who would like to know what life was like just a century ago in a rural Florida where priests still ‘rode the circuit’ to visit far flung parishes once a month.