Scottish born George Ballentine came to the United States at age 20 in 1845 for the same reason millions of others have over the years; he needed a job.

Shortly after he landed in New York, after a few drinks with a new mate, he signed on to a whaling ship. After a few more drinks he figured out that might not have been such a good idea, so the next morning he joined the U.S. Army.

He had spent a couple of years in the British Navy, sailing around off the coast of Africa. He knew the military life and sailing, so it was not an uninformed choice.

He signed up at Governor’s Island, New York, immediately started drilling to learn the Army way, and in a few weeks was transferred first to Rhode Island, and then to Florida. This was right after the Second Seminole War, the longest and most costly Indian War in America’s short history. The government was committed to keeping a large military presence in Florida.

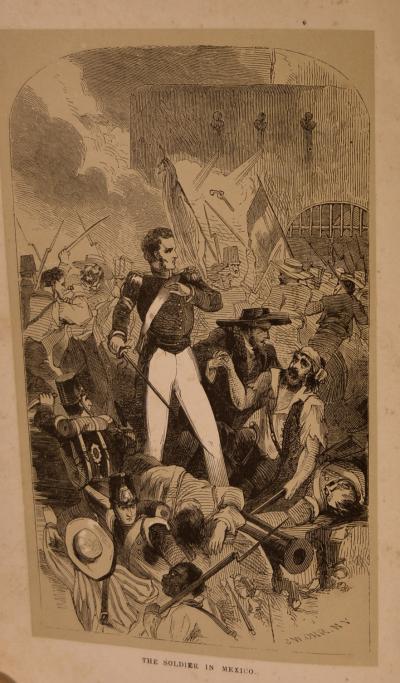

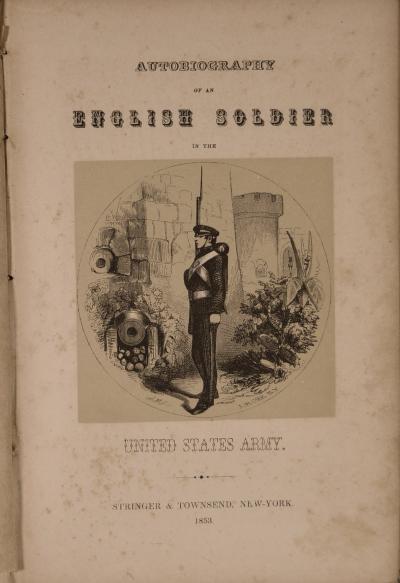

Ballentine would go on to see action in Mexico. We know all this because he kept a journal, and in 1853, still in his 20’s, he wrote an autobiography, touted by the publisher as the first account from the front lines by ‘an ordinary soldier.’

A copy of this first edition printing is in the archive at the Library of Florida History in Cocoa.

His first assignment was Ft. Pickens in Pensacola. His account of their arrival evokes Old Florida: “After a prosperous voyage of 16 days the low, sandy coast of Florida became distinctly visible. The first appearance of land on approaching Pensacola is very singular. Long bright lines of silvery white, crowned by a mass of dark green vegetation stretch far athwart the blue horizon suggesting the idea of a strong surf everywhere rolling in upon the shore.”

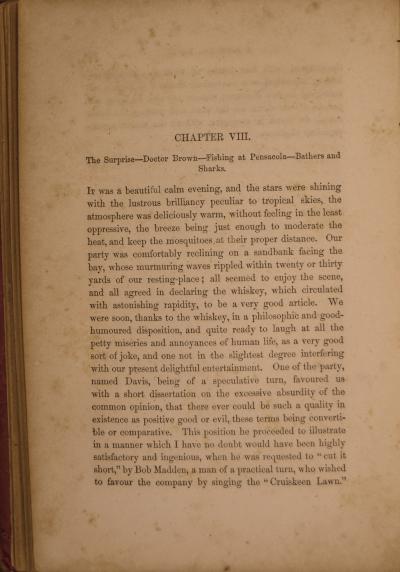

He went on to discuss one of the main characteristics of military life; monotony. And, the proliferation of home-made whiskey. And, sharks in the bay. Big ones. He noted one they caught, “on the beach alongside the wharf. The shark was dispatched with bayonets and cutlasses. When measured it was found to be 11 feet long, [with] frightfully capacious jaws filled with jagged saw like teeth ... taken out of the head and preserved by the ordinance sergeant. When fully extended the jaws would open enough to easily admit a stout man’s shoulders along them.” Boosted by the whiskey the men would dare each other to swim in the bay.

He also spent some time in St. Augustine, but most of his service was in Tampa.

There, the fort was in the middle of what is now downtown Tampa, so there was a bit more community life. His description of the camp would lend an air of sophistication to any modern travel folder: “In front of the barracks there stood a noble grove of Live Oak Trees which afforded a delicious shade from the scorching heat of the Sun and gave an air of quiet and expression of sylvan beauty to the scene. The long gray beard of weird like Spanish moss that droops in huge masses from the rough brawny arms of these giants of the prime evil forest gives them a venerable and druid able appearance which is exceedingly picturesque.”

The closest he came to the erstwhile enemy during his two year stay was when a group of 20 to 30 Seminole ‘warriors’ came to the fort “trading deer skins for things, including whiskey, and metal goods, tools, muskets, powder.” He says he and a lot of the soldiers stationed there felt bad for the Seminoles. He would have been happy to leave them alone if they wanted to live there.

Ballentine’s Autobiography of an English Soldier in the United States Army is a bit different. There are not that many of these firsthand accounts by 19th century soldiers, especially not ones published that early. Most were by officers and generals. Then as now, the view is different for the person in the boots on the ground.