Florida may now be one of the top Thanksgiving/Christmas/Hanukah/Kwanza /New Year holiday destinations in the world. But, in 1837, not so much.

For the American soldiers in the midst of the Second Seminole War it was a mosquito infested wilderness where they might have gotten a couple of hours, or even a day off from war and training to observe the day. A diary from the time, available at the Florida Historical Library both in its original hand written form and a typeset later edition, gives some insight into what passed for a holiday party at the time.

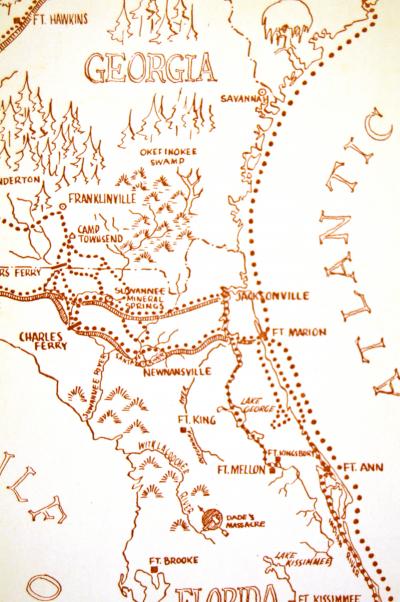

It didn’t take the U.S. Army long to figure out during the Second Seminole war that they had to place their forces in wide spread areas if they were to have any hope of tracking down the small bands of Seminoles. Nor did it take them long to realize if they were going to do that, they needed forts and stockades to shelter in. The Seminoles, who knew the terrain, had no trouble locating the loud bands of marching soldiers.

Today the aptly named Fort Christmas (http://www.nbbd.com/godo/FortChristmas/), recreated east of Orlando is perhaps the best known of these encampments. But the one in this Christmas story is Fort Ann, little more than a crude stockade built in what is now north Brevard County, in the Merritt Island Wildlife Refuge just north of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center property.

The military strategy was to send three columns of soldiers south through the Florida peninsula, west, middle and east, to flush out the Seminole bands. The east column used the Mosquito Lagoon and Indian River to move quickly through what is now Flagler, Volusia, Brevard and Indian River Counties. A company of soldiers in that east column, under the command of 1st Lieutenant James R. Irwin, built the structure in November 1837 near the convergence of the river and the lagoon. He reportedly named it after “the prettiest girl in Pennsylvania.”

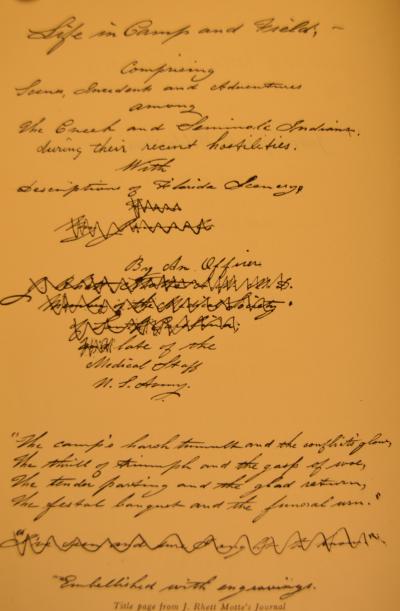

A young man named Jacob Rhett Motte (1811 – 1868), described as “a versatile army surgeon with a literary flair”, was assigned to the column. He was Harvard-educated and something of a southern gentleman immersed in the aristocratic social circles of Charleston, South Carolina when he applied to the Army, was accepted and suddenly found himself slogging through the mosquito, snake and gator infested wilderness of frontier Florida.

Naturally, he did what any respectable, educated man of that era would do,

He kept a journal.

According to accompanying documents, the hand written version of the journal in the Library’s collection is Motte’s edited copy, apparently prepared after his return to civilization; a second draft if you will.

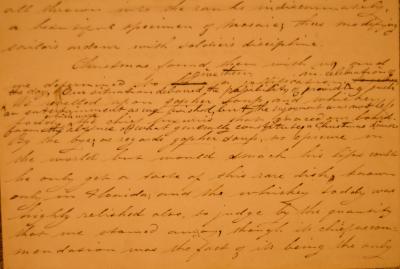

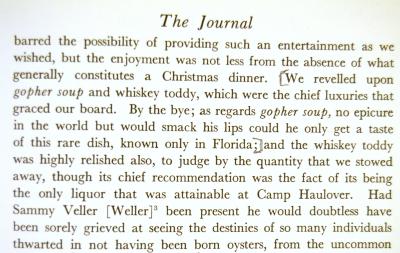

It still can take us directly to that Christmas in 1837 when men got a few hours off from military drills to enjoy what bounty was available to them in wilderness Florida, “Gopher soup and whiskey toddy”. Christmas came only once a year he noted, except in the years when military activity precluded it. Apparently that made this particular Christmas, in a wood fort just a few miles from where, someday, men and women would ride into space, special in the mind of this Southern gentleman.

The fort was abandoned in April, 1838.

Motte’s journal was edited by historian and military scholar James F. Sunderman and published in 1953 by the University of Florida Press as Journey into Wilderness. (see a review at: file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/OBJ%20datastream.pdf, p300 )

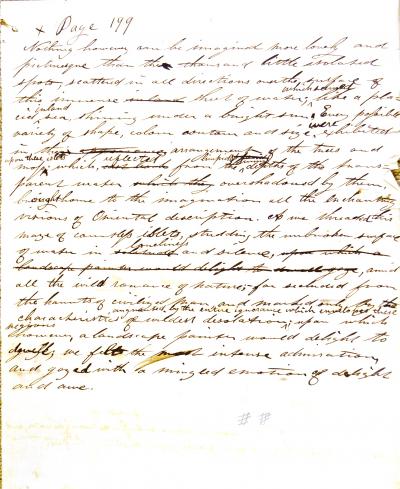

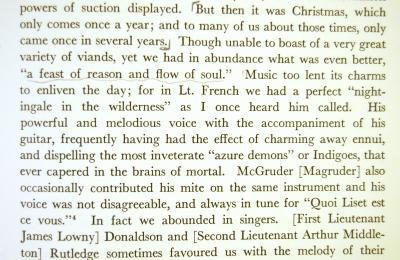

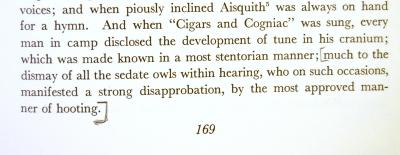

A close look at his work makes it easier to enjoy Motte’s style:

Much has changed in Florida in the last two hundred or so years, but Motte does share one continuing attraction. On New Years Day, 1838, he mentions “taking a dive” into the Atlantic.