It is likely you have heard the term “Conch Republic” applied with pride to Key West and its residents. It is less well known the term “Conch” is used elsewhere in Florida for folks who settled here from the Bahamas.

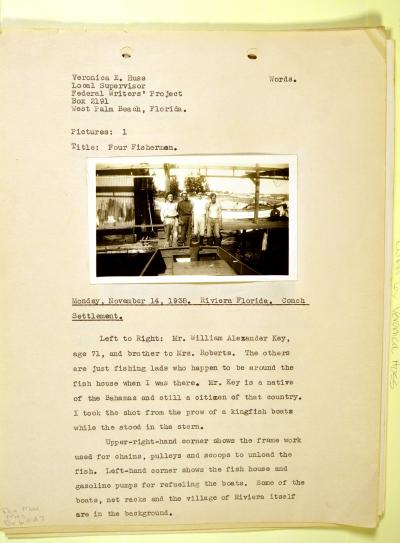

A collection of Works Progress Administration (WPA) photographs at the Library of Florida History documents one such group in an area now known as Riviera Beach in Palm Beach County. The photographs, taken in November, 1938, are attached to sheets fully describing the image and documenting the content. It is an invaluable look at everyday life in a long lost Florida village. It is also a collection that almost never happened.

The term “Conch” is applied to settlers who came to the Bahamas from a specific part of London starting in the 1600’s and continuing until about the start of the American Revolution. They only totaled a few thousand, and lived mainly in small communities around the islands. Some were small farmers, most lived off the sea, as fishermen and sailors. From the beginning they had strong ties to Florida and in the mid 18th Century they had a significant presence in the Keys, where they visited to catch turtles, cut lumber and salvage wrecks. Naturally, many of them took up residence in the Keys, and the term began to be applied to white settlers from the Bahamas throughout the Keys.

Why “conch”? There are several theories. Perhaps it was because shellfish formed such a large part of their diet. In any case the people apparently applied it to themselves as a term of distinction.

The ties between Florida and the Bahamas took another twist at the end of the Revolution. The Florida colonies (East Florida and West Florida) stayed loyal to the King during the war, and expected to remain in the Empire after the war. However, they were dealt away to Spain in post-war negotiations, and hundreds left Florida for the Bahamas to remain under English rule.

They made a life there, but there was something of a reverse immigration wave once Florida became part of the United States and through the mid 19th-century. Then, in the early 1900’s economic conditions in the Bahamas took a downturn. Farm lands became exhausted and demand for fish decreased and migration to Florida experienced an uptick.

Most went to the Keys, but between 75 and 100 families formed a settlement in Palm Beach County on the shores of Lake Worth and the estuary system that separates the mainland from Singer Island, called “The Riviera”. That migration continued through the 1920’s.

This close knit group of families, descended from the original British settlers in the Bahamas, brought their boating and fishing skills, along with wonderful folk tales and songs, a mix of Caribbean and English culture, with them. They incorporated “Riviera Beach” in 1922 to keep from being annexed by neighboring West Palm Beach, where residents took to calling the new community “Conchtown”. It was not intended as a compliment. As an un-cited Wikipedia entry puts it:

Unlike the situation in Key West and the rest of the Florida Keys, where being "Conch" became a matter of pride and community identification, "Conch" was used by outsiders (in particular the residents of West Palm Beach) in a pejorative manner to describe the Bahamian community in Riviera Beach. The usage there also carried the connotation that at least some of the "Conches" were of mixed racial heritage.

It was that close knit group of second generation settlers that WPA writers, photographers and anthropologist Stetson Kennedy came to record in the late 1930’s.

The photos capture the work-a-day world of the men who made a living on the sea,

and, with the accompanying documentation, offer an insight to the economic reality of the times. The paper with this picture of a ‘fisherman with cast net’ identifies him as 47 year old Claude Smith, from Indiana, a “[First] World War” vet, partially disabled but working as a fisherman to support a wife and children.

The young (about 21 in 1938)author of this collection, WPA Florida Writers Project worker Veronica Huss, who grew up in LaBelle, Florida, was often blunt in her assessments.

In the caption for the picture titled “A Typical Conch Home” she wrote “This home is typical of the poorer homes in Riviera.”

And the picture of a house with more amenities is simply called “Better class Conch home.”

Huss documented the workplaces; the fish house and boats.

She documented the community buildings, such as the simple building used as a church.

And she documented the people, including Mr. and Mrs. William Roberts; in their 80’s, Bahama born, who had been in the community since 1900, first on Singer Island and then, after being pushed off the island, in Riviera. They possessed the cultural memory, the institutional knowledge Huss tapped into by living with the family for a year as she prepared to write a book on “Conch Town.” It was not to be.

At first, the WPA appeared supportive. They assigned an artist and photographer, Charles Foster of Jacksonville, to document her story. He spent a day taking pictures of her and her subjects. Then the WPA decided to illustrate the book with drawings based on his pictures. Then the WPA decided not to publish it at all. In fact, the popular WPA Guide to Florida includes only one paragraph about the Conchs.

The recordings and transcriptions of songs and folk tales Huss, with folklorist Stetson Kennedy, collected eventually were archived at the Library of Congress, and Foster first made a traveling exhibit of some of the photographs he took and, in 1991 published a book of the photos and Huss’s research called “Conch Town, USA; a Small Story of a Small Town Now Gone.”

Exactly how these particular photos, perhaps taken by Huss herself and fastened to the pages she typed up, ended up in the Florida Historical Society Library is something of a mystery. Perhaps they were presented by state WPA officials who were active with the society. Without that good fortune this personal look into a now vanished community would be as lost as Conch Town.