Three sisters entertained Union soldiers in their St. Augustine home during the Civil War, carefully gathering information. While two sisters continued to distract the soldiers, the third, Lola Sanchez rode a horse through backwoods and marshes to relay Union plans to Confederate forces.

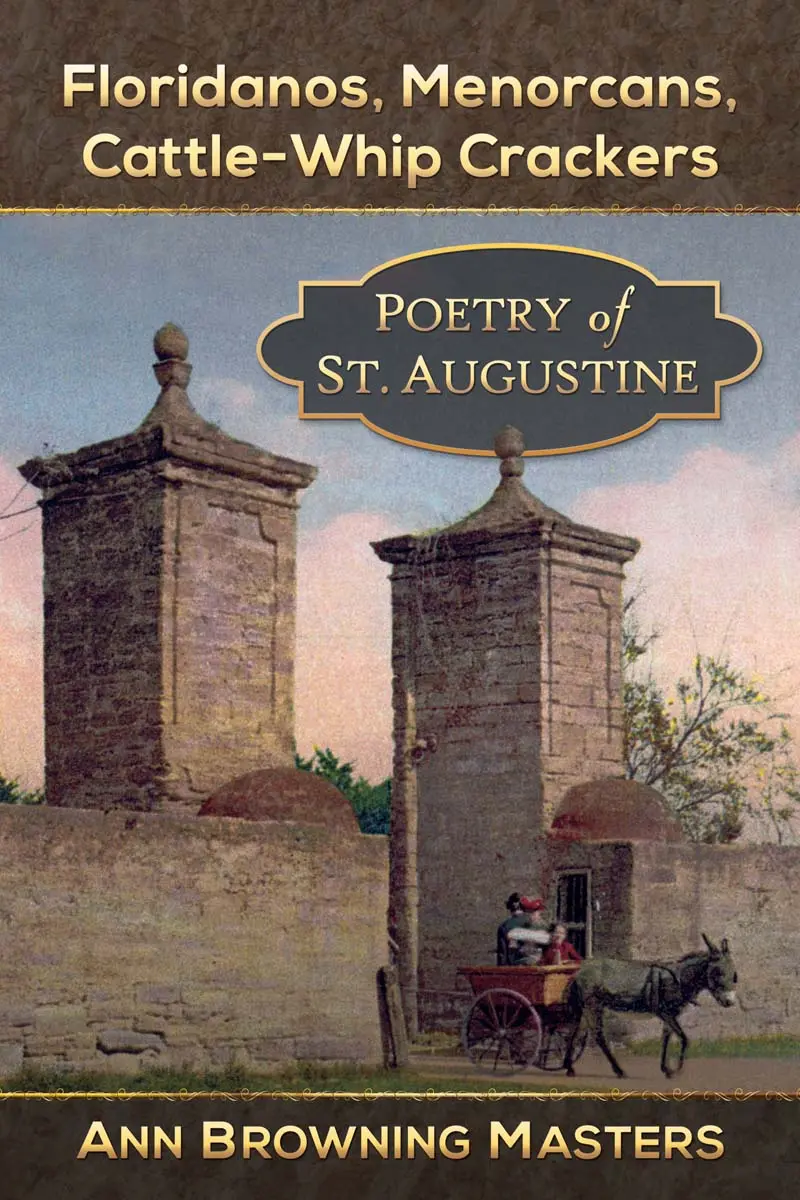

Poet Ann Browning Masters is related to the Sanchez sisters and writes a poem from Lola’s perspective in the new book “Floridanos, Menorcans, Cattle-Whip Crackers: Poetry of St. Augustine.”

Masters will be discussing her work Friday evening at 7:00 at the Library of Florida History, 435 Brevard Avenue, Cocoa. The presentation is free and open to the public.

The Spanish established St. Augustine on September 8, 1565, making it the oldest continuously occupied European settlement in what would become the United States. Descendants of those Spanish settlers are called “Floridanos.”

A twelfth generation Floridian, Masters can trace her lineage back to the early days of America’s first permanent European settlement, making her a Floridano.

“In St. Augustine on my mother’s side, her family records that are first there in the records with the Catholic Church are in 1602, when Elena Gonzales married Diego Alvarez,” says Masters.

“For almost a hundred years, her daughters, granddaughters continued to marry men who came to St. Augustine. They stayed there. Then in 1704, Juana Perez, one of those great-granddaughters, married Jose Sanchez. So my family line maternally, goes with the Sanchez family. My mother’s maiden name is Sanchez.”

The First Spanish Period in Florida ended in 1763, when the British took control of the region for twenty years. During the British Period, Scotsman Andrew Turnbull brought indentured servants to Florida to settle New Smyrna. The term “Menorcan” is used to describe these people and their descendants, although not all of them were from the island of Menorca.

“They are of Italian, Greek, and Menorcan descent,” says Masters. “Menorca is one of the Balearic Islands southeast from Barcelona (Spain) and at the time, Menorca was under control of Britain, so it made sense that a British land owner would recruit indentured servants from this Spanish, basically, island of Menorca.”

The Turnbull Plantation failed, and the indentured servants from New Smyrna fled north to St. Augustine where they were provided sanctuary.

“The paternal side for me is the Menorcan side,” Masters says. “In my mother’s Floridano side, they married some Menorcans. So for me, it’s a blending of those two cultures.”

It is a popular myth in St. Augustine that hot datil peppers arrived in the area when Menorcan settlers brought them there. Extensive research and three trips to Menorca have convinced Masters that the legend is not true.

What is a fact is that Menorcans in St. Augustine have been cooking with datil peppers for many generations, as Masters explains in her poem “The Menorcan St. Augustine Litmus Test.” In the poem, she says that if you enjoy eating the burning hot peppers and ask for more, you can be called “a good Menorcan.”

The third group named in the title of Masters’ poetry collection, and the third part of her ancestry, is “Cattle-Whip Crackers.” The word “cracker” probably originates with the William Shakespeare play “The Life and Death of King John” where talkative Scotch-Irish people are called “crackers.” Those people eventually came to Florida as pioneers.

“There are so many origins for the word. We can go back to the Scotch-Irish, the craic, the talk at the pub and a good time. In America, the corn crackers, that’s another derivation. In this case though, what I’m talking about are people who owned cows, had ranches. In the South we would say they ‘ran cows.’ Growing up, that was my understanding of the term, although at the same time it did have that pejorative term of a racist that it has now. But that’s another usage for that term.”

In her book “Floridanos, Menorcans, Cattle-Whip Crackers: Poetry of St. Augustine,” Masters explores her personal heritage, but also addresses historical topics and perspectives.

“For me, the local language, the vernacular is poetic. When I hear this speech, I hear the voices speaking narrative poetry. That’s why many of the poems are almost like monologues with characters telling their story. That’s poetry for me.”