In 1738, the first legally sanctioned free black settlement was established in what would become the United States.

El Pueblo de Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, popularly known as Fort Mose, was a community of former slaves who pledged allegiance to the King of Spain, became Catholic, and agreed to defend Spanish controlled Florida from invaders.

Located just north of St. Augustine, Fort Mose was the first line of defense against attack from British colonies.

As part of the War of Jenkins Ear between Spain and Great Britain, General James Oglethorpe led an invading force into Spanish Florida. In the early morning of June 26, 1740, that invasion was repelled at Fort Mose.

Since 2010, an annual reenactment of the Bloody Battle of Fort Mose has been staged at Fort Mose Historic State Park. Several groups of reenactors participate in the event, coordinated by Florida Living History, Inc.

“This is a reenactment of the surprise attack, in June of 1740, that the Spanish soldiers in St. Augustine, the black militia from Fort Mose, and Yamasee auxiliaries launched to recapture the Fort Mose site from British and Scottish invaders from Georgia and Carolina,” says Davis Walker, president of Florida Living History, Inc.

“The attack was launched just before dawn,” says Walker. “The defending forces were caught completely by surprise and basically massacred.”

The Bloody Battle of Fort Mose successfully ended Oglethorpe’s siege of St. Augustine, and returned control of Florida to the Spanish.

Fort Mose was destroyed during the battle, and it would take twelve years to rebuild the outpost.

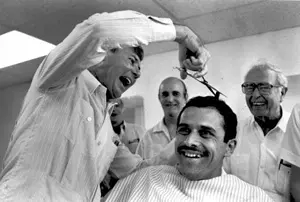

Florida Living History, Inc. presents a variety of historical reenactments throughout the year, but the Bloody Battle of Fort Mose allows collaboration with other groups. British and Scottish reenactors come from Fort King George and Fort Frederica in Georgia. People portraying Spanish soldiers come from all over Florida. The Fort Mose Militia provides black soldiers, and Yamasee Indian reenactors come from Tampa and St. Augustine to participate.

“We’ve always thought that this would make such a unique living history event because it involves European, black, and Native American elements,” says Walker. “Happily, our friends at the Florida Park Service and here at Fort Mose encourage that very strongly, and have been working hand and hand with us to grow this event. Also, the Fort Mose Historical Society, a volunteer group that supports the park, has taken part.”

Andrew Batten, director of attractions at the Brevard Zoo in Melbourne, travels to St. Augustine to participate in the Bloody Battle of Mose reenactment. Batten portrays a member of the South Carolina Rangers, one of Oglethorpe’s militiamen. There were about twice as many Spanish troops at Fort Mose as there were British soldiers.

“You have four different (British) units within this, all doing things different ways,” says Batten. “The other problem is that you have soldiers like myself, who are trying to make a little money on the side. If I capture Spanish horses, I can sell them to the British army, and I can make much more money doing that than I can doing my job. So the South Carolinians who are here, unfortunately, were poorly led, they had poor morale, very poor discipline, so you see the results in what became known as Bloody Mose. Of the 137 British troops here, 25 got out unharmed or uncaptured or alive.”

Fort Mose Historic State Park, a National Historic Landmark, is where the battle reenactment takes place each year. A boardwalk takes visitors to marshlands where the original Fort Mose stood. The battle reenactment takes place on uplands adjacent to the marsh.

A museum at the site tells the story of America’s first free black settlement.

“We have a $750,000 interactive and interpretive museum where the exhibits actually respond to your movement throughout,” says Thomas Jackson, vice-president of the Fort Mose Historical Society.

The museum is open 9am to 5pm Thursday through Monday, and is closed Tuesday and Wednesday.

In addition to the Bloody Battle of Fort Mose reenactment in June, the Fort Mose Historical Society presents Living History programs during the last weekend of every month. These programs include demonstrations of food, the firing of muskets, and portrayals of historic figures.