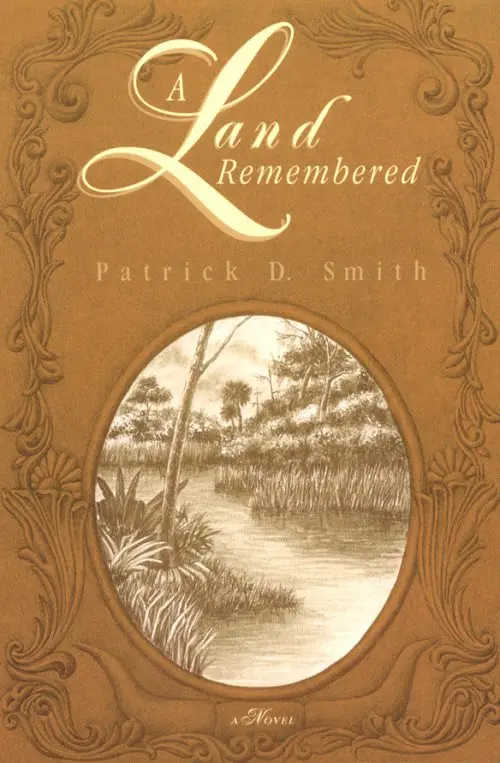

Patrick D. Smith’s 1984 novel “A Land Remembered” is one of the most popular books about Florida ever written.

The beloved Merritt Island author was born October 8, 1927, and died January 26, 2014. He would have been 88 this week.

Most popular novels have a year or so of commercial success, perhaps getting another boost when a paperback version comes out. Smith’s “A Land Remembered” has been a bestseller in Florida since it was first published.

“You know, that’s hard to understand sometimes,” said Smith. “Every year it gets more and more readers. It’s really gaining with young readers. Most of the schools in Florida now teach it. The young kids really like it, because they had no idea that Florida was ever like it’s depicted in ‘A Land Remembered.’”

It’s not just young readers who love “A Land Remembered.” Many lifelong Floridians say that if you are only going to read one book about the history and culture of the state, then this novel should be it.

The novel “A Land Remembered” follows the fictional MacIvey family for more than a century, from their arrival in Florida in 1858 through 1968. The family struggles at first to live off the land, but becomes very successful in the cattle industry. The last generation covered in the book loses connection with the land, selling it off for development.

“The last of the MacIveys, Sol, is the one who built all those structures and came to regret it,” said Smith. “Before he died, he gave a lot of the land to the state to be preserved forever as wildlife preserve. So, he regretted what he had done.”

In the novel, pioneer life is difficult for the MacIveys as they face hurricanes, freezes, and mosquitos capable of killing cattle. They have conflicts with cattle rustlers and Confederate deserters, but develop friendships with Native Americans and African Americans who are also struggling to survive in the Florida wilderness.

“I wanted to make that family real, to show what they really went through,” said Smith. “Not just telling readers there was a Great Freeze in 1895, but showing how that affected this family, and how they were affected by the coming of the railroads, and the birth of the cattle industry and the Civil War. Later on, how they were affected by the great land boom down in Miami in the 1920s, and that hurricane that hit Lake Okeechobee in 1928 and killed over 2,000 people. These are all things that really happened in Florida, but the really important thing to me was to show how they affected people.”

No one family experienced everything that the MacIveys did, but almost everything in the book did happen to one pioneer family or another.

“That book is not based on one family,” Smith said. “The characters are composites of different families. I’ve had at least a dozen families in this state swear to me that the book is about their family because they identify with it.”

“A Land Remembered” was recognized by the Florida Historical Society when it was first published, earning the Charlton Tebeau Award for Best Novel based on Florida history.

In 2012, Patrick Smith won the State of Florida’s Lifetime Achievement Award for Writing.

Smith had success with other books including “The River is Home,” “Allapattah,” and “The Beginning.” His novel “Angel City” was made into a film starring Paul Winfield, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and Ralph Waite.

“It’s seven novels all together,” said Smith. “Only one of them was really as popular as ‘A Land Remembered.’ That was ‘Forever Island.’ It’s been published all over the world. There’s not too many writers left in Florida who’ve been at it as long as I have. My first novel, ‘The River is Home’ was published in 1953. I’ve written a total of ten books. I know that’s not a lot of books, but you know, I did it at the same time I held down a full time job, and that makes a lot of difference.”

Smith was placed in the Florida Artists Hall of Fame in 1999 to commemorate his full body of work, but he will always be best remembered for “A Land Remembered.”