The Labor Day Hurricane that struck the Florida Keys on September 2, 1935 is the most powerful storm to ever hit the United States. With wind gusts estimated up to 225 miles per hour and a storm surge bringing waves as high as 20 feet ashore; the hurricane was devastating.

Nearly half of the 1,000 people who were on the Florida Keys when the hurricane arrived were killed. Among the dead were about half of the 300 World War I veterans working on road construction projects there for the federal government.

“In 1935, this is the height of the Great Depression, so a number of Americans were out of work,” says Ben DiBiase, archivist at the Library of Florida History. “FDR and the federal government were trying to get a lot of people back to work. Unfortunately, these veterans were working in the Keys at the wrong time, during the height of the hurricane season.”

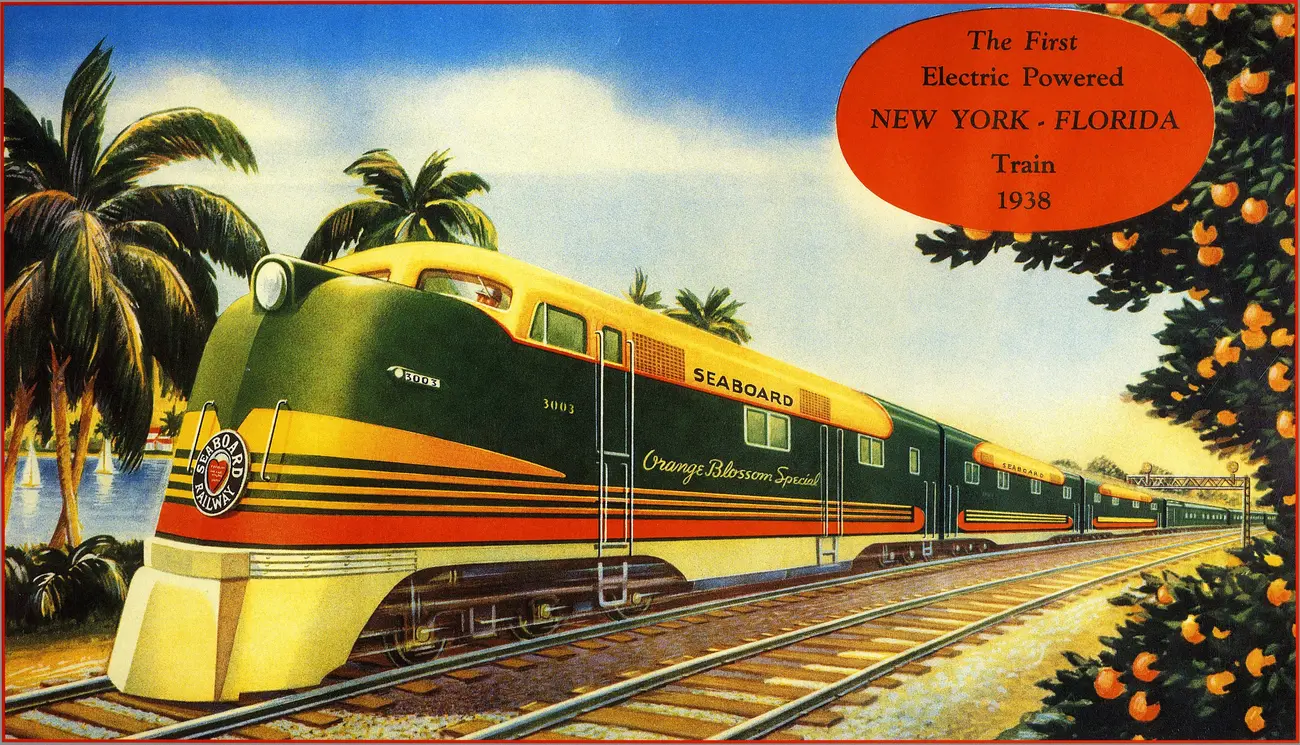

Tragically, by the time a decision was made to send a train from Miami to rescue the veterans and others living in the Keys, it was too late.

“The train left late and on its way down it had to stop at the Miami River because the drawbridge was raised to let holiday traffic through,” says Tom Knowles, author of the book Category 5: The 1935 Labor Day Hurricane. “Then it had to stop in Homestead to turn the engine around so they could back it down. The idea was to have the engine in the lead when it came back so it could use its headlight.”

Unfortunately, the delays for the rescue train’s arrival did not stop there.

“At Windley Key, the cab of the locomotive struck a cable that was normally hung over the railroad, but because of the hurricane had sagged down,” says Knowles. “It took about another hour to break that loose. By the time the train got down to Islamorada it was a little before 8:30, and that was when the storm surge came over.”

The storm literally pushed the train off of its track. All cars but the engine and its tender were turned over on their sides.

Renowned Florida writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas, best known for her classic book Everglades, River of Grass, wrote about the 1935 Labor Day storm in her book Hurricane:

“At the veterans’ barracks the men packed up and moved out to huddle along the railway embankment, waiting for the train. They had to cover their faces because the stinging sand began to draw blood. Every once in a while one would say, ‘It’s coming. I hear it.’ It was the wind coming in faster and faster over the bent trees with the high shaking hurricane rumble that sounds exactly like the never-ending passing of a freight train.”

The rescue train would never arrive.

Acclaimed writer Ernest Hemingway was living in Key West when the hurricane hit, and he participated in the effort to rescue survivors of the devastating storm. In an article he wrote for the magazine “The New Masses,” Hemingway implied that the Florida Emergency Relief Administration did not act quickly enough to evacuate the veterans.

On January 22, 1912, Henry Flagler realized his dream of completing the Overseas Railway, linking Miami to Key West. The Labor Day Hurricane of September 2, 1935 destroyed 42 miles of East Coast Railway track, and the rail link to the mainland was never rebuilt.

People driving to the Keys today can see portions of the Overseas Railway bridges rising from the water, disconnected from the land and leading nowhere.

A memorial to the people killed in the 1935 hurricane stands on Islamorada between the old state road 4A highway and U.S. 1 at mile marker 81.5.

“Islamorada, which was a small community at that time, was completely wiped off the map,” says DiBiase. “It simply disappeared. The citizens who were living in the Upper Keys, they only numbered a few hundred, many of them lost their lives or at the very least lost everything that they owned.”

About 1,000 people were in the Keys in 1935, and could not be successfully evacuated. Today, an estimated 80,000 people would need to leave for a similar hurricane.