Former Florida Senator Bob Graham co-chaired the congressional inquiry into possible links between the Saudi Arabian government and the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and since 2002 he has wanted the commission’s full report released. Twenty-eight pages had been removed from the document and labeled “classified.”

On July 15, the missing “28 pages” were finally made public.

The newly released document states that, “While in the United States, some of the September 11 hijackers were in contact with, and received support or assistance from, individuals who may be connected to the Saudi Government.”

The report says that the congressional commission was presented with information “indicating that Saudi Government officials in the United States may have other ties to al-Qa’ida and other terrorist groups.”

The commission adds the caveat that much of the information presented as part of the inquiry “remains speculative and yet to be independently verified.”

As co-chair of the commission, Graham was frustrated that their full report was not initially released.

Graham tried to share information about the terrorist attacks with the public, but was sometimes prevented from doing so.

As a senator and member of the CIA External Advisory Board, Graham had to submit anything he wrote about the agency for approval before publishing. He had two non-fiction books partially dealing with 9/11 significantly edited by the CIA.

Graham’s political experience clearly informs his suspense novel, “Keys to the Kingdom.”

“The reason I wrote the novel was because I felt that there was some important unanswered questions coming out of 9/11. One of those was ‘what was the full extent of Saudi Arabia in assisting the 19 hijackers?’ Number two, ‘why would Saudi Arabia have turned against its strongest ally to assist what was our and their great enemy, Osama bin Laden?’ And third, ‘why has the United States gone to such lengths to cover it up?’ I’ve tried in non-fiction to tell those stories, and been frustrated by censorship, and so I decided I would tell the story as a novel, where the standards of censorship are lower, since you’re not representing this to be the truth. But in fact, forty percent or more of this novel is truth.”

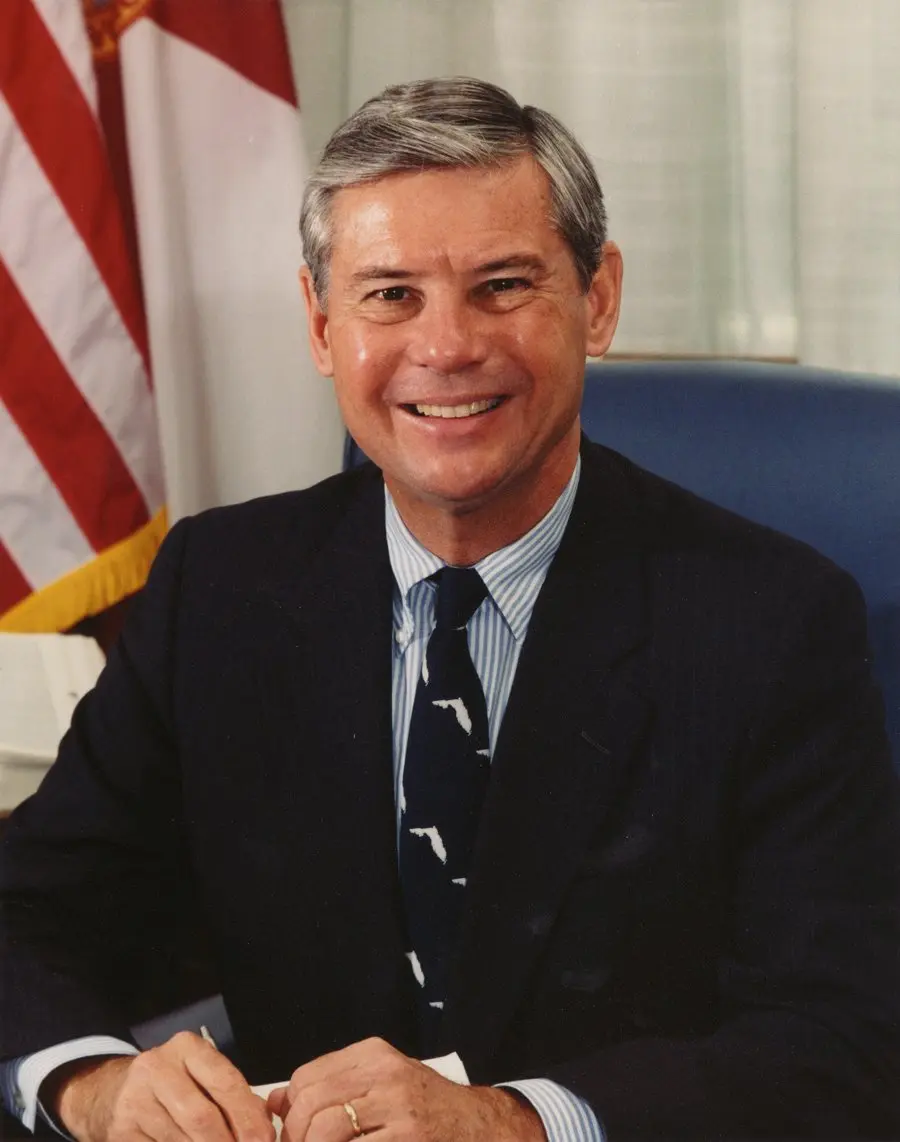

Following two successful terms as governor of Florida, Graham spent 18 years in the United States Senate. He served 10 years on the Senate Intelligence Committee, both before and after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Graham was one of the voices raised in opposition to the subsequent war in Iraq, which he says was one of his proudest moments as a senator.

“I wasn’t proud at the outcome, because I was fairly convinced that it was not going to be a good outcome because we had been led into this war by false information,” says Graham, referring to the unsubstantiated claim that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction.

“The people who gave us that information knew, or should have known, that it was false,” Graham says.

Senator Graham has often been called “the hardest working man in politics.”

Graham’s 38 years of public service included two terms as Governor of Florida from 1979 to 1987, and he represented Florida in the United States Senate from 1987 to 2005.

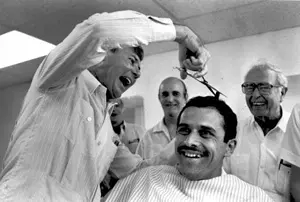

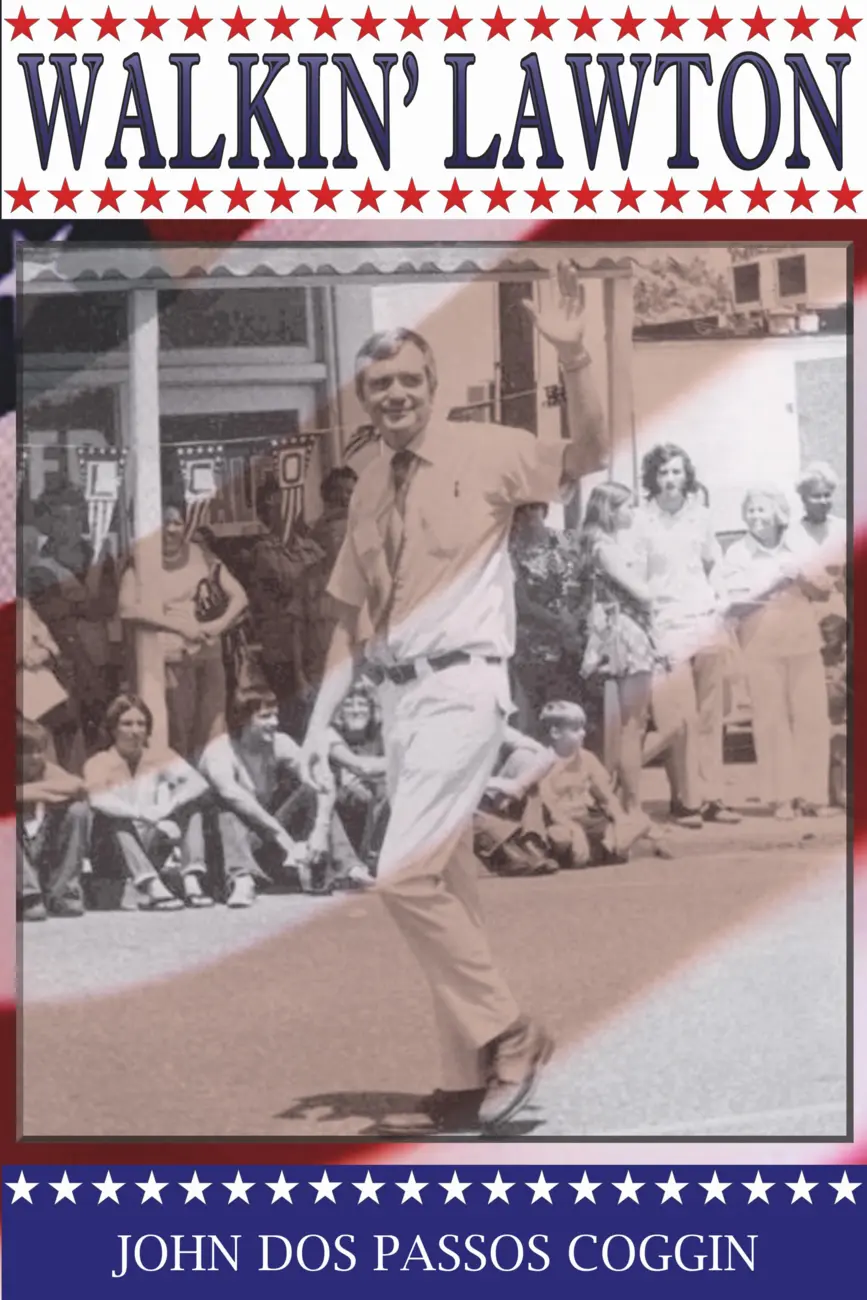

He famously spent more than 400 days working other people’s jobs, including days as a journalist, a fisherman, a construction worker, a truck driver, a barber, and in many other occupations.

Graham started his tradition of “work days” in 1974, while he was serving in the Florida Senate. His willingness to experience the lives of other people, if only for a day, helped to make Graham a very popular politician. He left office as governor with an 83% approval rating.

Since leaving the U.S. Senate in 2005, Graham’s primary focus has been on developing the Bob Graham Center for Public Service at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Graham learned about public service at a very early age. His father, Ernest R. Graham, was a cattleman who also served in elected office, inspiring his son’s political aspirations.

“He was very influential is an extremely positive way,” says Graham. “He had high values and he honored public service, and I tried to be faithful to his principles.”