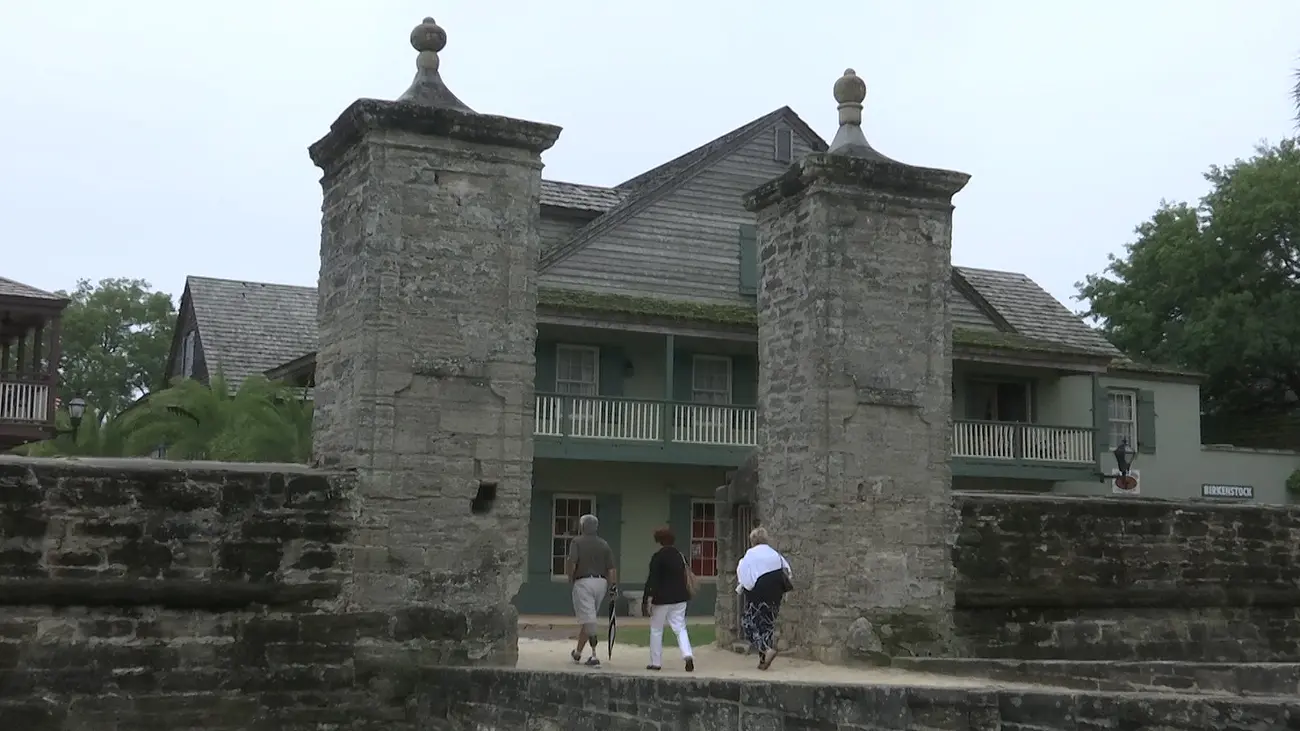

Every year in May, nearly 1,000 students from around the state meet in Tallahassee to compete in the annual Florida History Fair. Next month, the winners of this year’s competition will travel to College Park, Maryland to compete with state history fair winners from across the country.

“Florida History Fair is an opportunity for students from sixth grade to twelfth grade to participate in historical research and produce a product, either a documentary, an exhibit, a website, a historical paper, or a performance using primary sources,” says Trampas Alderman, curator of education at the Museum of Florida History, and coordinator of the state competition.

The student competitors at Florida History Fair must follow strict guidelines when preparing their papers, projects, and performances. They do not just present information they have collected. The students must demonstrate analysis and interpretation of their selected topics for the judges.

“They’re not just doing a typical paper you do in school,” says Alderman. “They’re doing what the professionals do. They’re looking at primary resources to develop a base from which to draw conclusions and to make historical analysis, just like a historian will do, or a curator at the museum.”

Beyond training students to use critical thinking skills to analyze and draw conclusions from available facts, an evaluation of National History Day conducted in 2010 concluded that there are many benefits for participants in Florida History Fair.

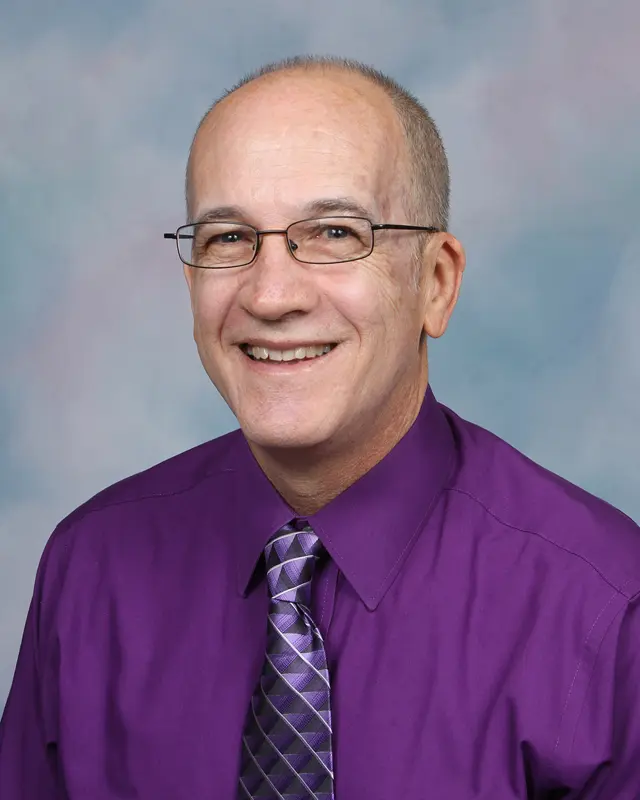

“Students who participate in the program perform better in high-stakes tests, are better writers, more confident and capable researchers, and have a more mature perspective on current events and civic engagement than their peers,” says Chris Bryans, a social studies teacher at Community Christian School in Melbourne.

“From a personal perspective, I cannot tell you how many of my own students have grown academically and socially through their participation in this program,” says Bryans. “I know I am not alone when I say that History Fair captures the interests and hearts of a lot of students who would otherwise slip through the cracks. It’s a lot of fun, too.”

This year nearly half of all Florida counties sent local student winners to compete on the state level at the Florida History Fair in Tallahassee. Brevard County had only two schools partipate.

Chris Bryans served as the coordinator of the Brevard County History Fair from 2009 through 2014, building the program to include ten participating schools. This year, his teaching schedule did not allow him to continue as the county coordinator.

“All we have to do to get it moving again is to have someone willing to take on the role of county coordinator,” says Bryans. “It doesn’t have to be a teacher or even someone within the district school system. All it needs is someone with the time and heart to help the schools organize, work with the schools and the district in organizing the county history fair in late February or early March, and be a liaison with the state history fair coordinators.”

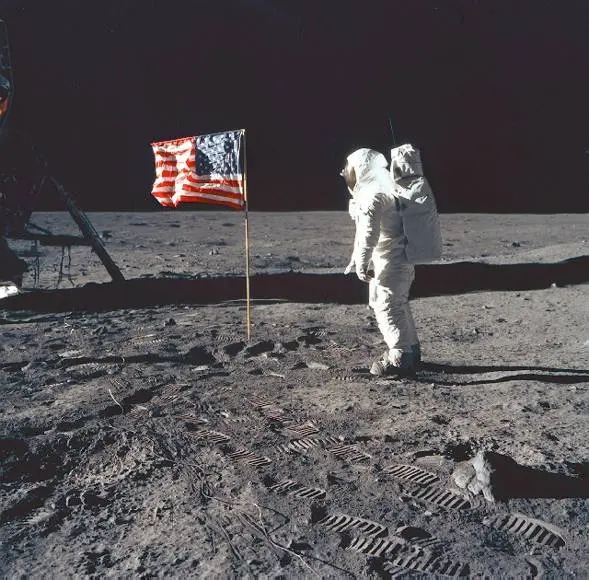

The theme for the 2015 Florida History Fair and the upcoming National History Day competition is “Leadership and Legacy.” Popular topics for student entries this year include entrepreneur Walt Disney, author Stetson Kennedy, and civil rights activist Rodney Hurst.

Someone could have done a project or paper on the “Leadership and Legacy” of Chris Bryans.

“All of my students are graduating this year and next with Florida History Fair under their belt,” says Bryans. “They have grown because of it. And what stories they have! How many folks do you know who got to spend time with the daughter of civil rights martyrs Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore, or who have spent a few hours getting to know a real Tuskegee Airman? Who wouldn’t treasure such opportunities and memories?”

Perhaps next year more students from Brevard County will once again be able to reap the benefits of participating in history fair on the local level, move up to the Florida History Fair, and maybe even make it to the National History Day competition.

“I have offered my six years of experience to help a new coordinator get started but haven’t had any nibbles,” says Bryans.