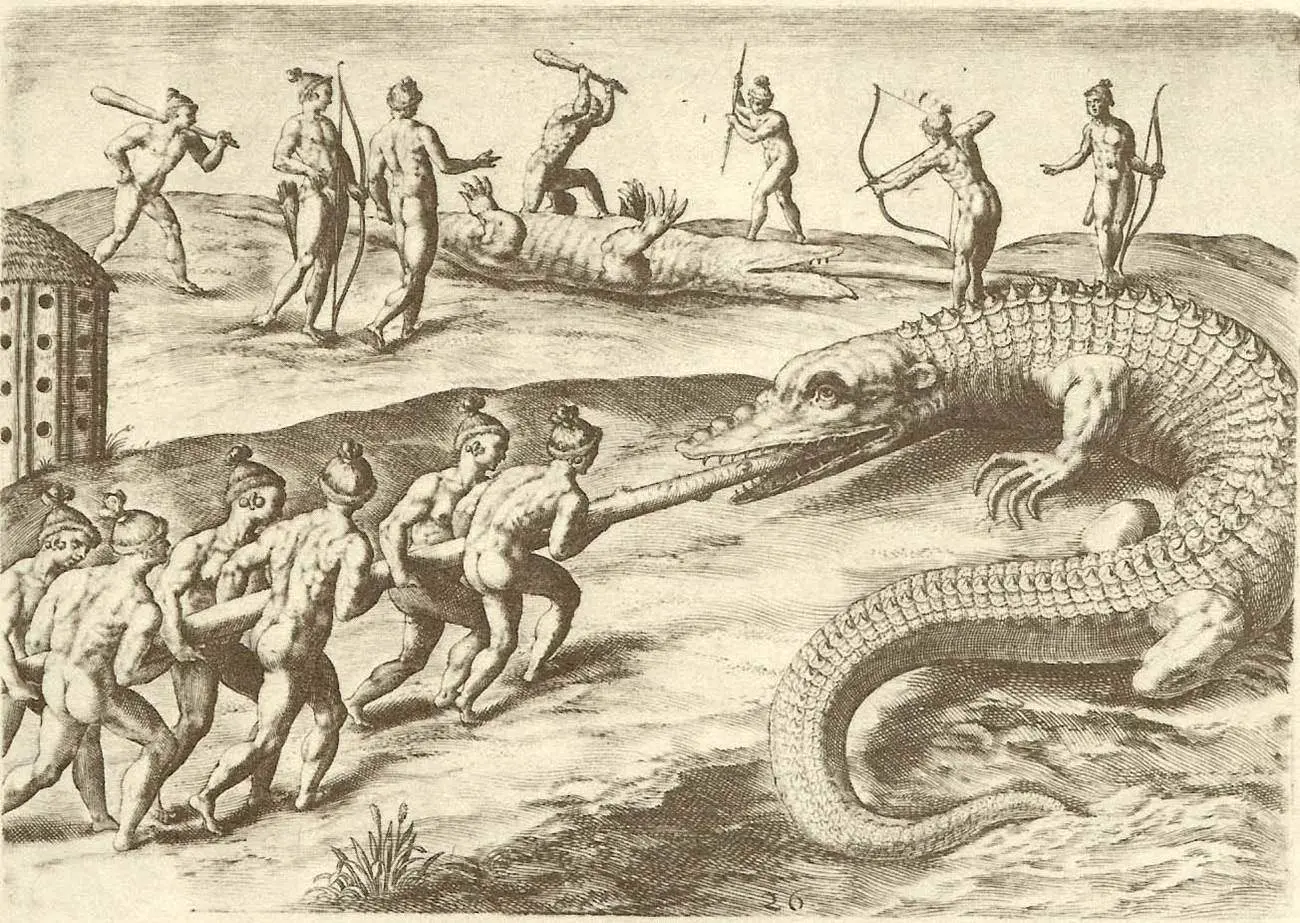

Since they were first published in 1591, the engravings of Theodore de Bry have been the most enduring images of Florida natives at the time of European contact.

“The de Bry engravings that were always thought to be based on Jacques le Moyne’s paintings have become the epitome of the best source for what Florida Indians looked like,” says Jerald T. Milanich, one of the most respected historical archaeologists in the state.

For more than four centuries, historians, archaeologists, artists, and the general public have relied upon de Bry’s images to provide information about the clothing, weapons, hair styles, headdresses, jewelry, tattoos, housing, baskets, canoes, cooking methods, and traditions of Florida’s Timucua Indians.

While some of what de Bry depicts in his engravings is supported by written historical descriptions, much of the content now appears to be the product of imagination, or based upon images of non-Floridians.

As Milanich and other modern scholars began to notice problems with the de Bry engravings, the list of discrepancies continued to grow.

“One was that the French soldiers portrayed in these engravings had their helmets on backwards,” says Milanich. “Another thing is that some of the engravings show Timucua Indians in north Florida drinking a sacred tea called Black Drink out of nautilus shells from the Pacific Ocean. We know that they drank it out of big whelk conch shells. So something was funny, something was weird about this.”

Another image shows Indians fighting a gigantic alligator with human-like ears and muscular arms.

De Bry was born in what is now Belgium, in 1528. He moved his family to London in 1585, before settling in Frankfurt in 1588. De Bry was a skilled engraver, known for his detailed images. Although he published books of images depicting Florida Indians and other native people of the New World, de Bry never visited the Americas.

“Everyone thought, including me, that although there were mistakes in these engravings, that they were based on paintings done by Frenchman Jacques La Moyne, who came to Florida in 1564 and did watercolors, probably after he returned to Europe,” says Milanich. “Those watercolors are lost, and may have never existed. Jacques le Moyne [may have] died before he did what he wanted to do. He talked with Theodore de Bry and gave him ideas.”

Close inspection of the 42 Florida engravings created by de Bry show that he borrowed imagery from a variety of sources, including books that his company published on other native cultures. Elements found in the Florida engravings were lifted directly from illustrations of Brazilian Indians.

“Not only did he do that for the volume he published on Florida, but he did it on volumes he published about other native peoples in the Americas,” Milanich says.

De Bry was also inspired by the work of artist John White, who visited North Carolina and painted the Indians there. White’s paintings of the Carolinian Indians are displayed at the British Museum. White also painted a Timucua Man and a Timucua Woman, and de Bry borrowed imagery from those pieces.

“John White never saw a Timucua man or a Timucua woman in his life, and what we know now is that he used his Carolinian Indians as models to do the Timucua Indians,” says Milanich. “He also used a French account by Jean Ribault that described the Indians as being heavily painted and the women wearing moss dresses.”

The de Bry engravings of Timucua Indians have been used repeatedly in books about the indigenous people of Florida, and inspired museum exhibits. Artists depicting Florida Indians have been influenced by de Bry’s images when creating their own work.

“I wrote a book about the Timucua Indians [published in 1996] and a lot of information I put in that came from those engravings,” says Milanich. “I got lucky, because I also used other historical documents.”

Milanich says that we must now question all of the conclusions reached using the de Bry Florida Indian engravings as a source.

“We thought we had a wonderful source, a code, a portal into the past, and suddenly things aren’t as we expected or as we thought,” says Milanich. “That often happens. Maybe someday we’ll find another source.”