Some of the world’s most powerful leaders have made important decisions while staying in a relatively modest residence in Key West, Florida.

Seven Presidents of the United States have stayed at the Harry S. Truman Little White House. The home bears Truman’s name because he was the one who most fully utilized the facility while in office, spending nearly six months of his presidency in his second home.

“It’s somewhat unique,” says Robert Wolz, executive director of the Harry S. Truman Little White House Museum. “The only location quite similar would be Camp David,” the presidential retreat in Frederick County, Maryland.

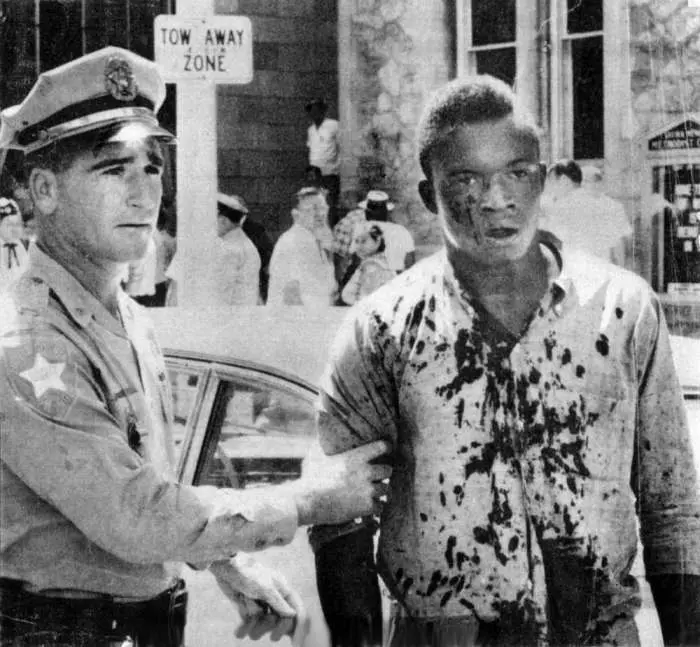

Truman’s presidency saw the end of World War II with the use of atomic weapons on Japan, the founding of the United Nations, the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe, the start of the Cold War with the Soviet Union, and the racial integration of the military and federal agencies.

The Little White House was more than just a vacation retreat for President Truman. While working in Key West, he signed documents that would advance civil rights, help lead to the creation of Israel, and result in the firing of General Douglas McArthur.

“They were literally running the country from Key West, Florida,” says Wolz. “He actually was enacting legislation from this site. It all reads ‘The White House, U.S. Naval Station, Key West, Florida.’ So, Harry Truman is our first president to realize that where the president is, there the White House is.”

The home was originally constructed in 1890, as a Navy Officer’s residence.

The first president to stay at the house was William Howard Taft, in 1912. “Taft came via Flagler’s railroad and then sailed from Key West to Panama to see the building of the canal,” says Wolz. “He was very instrumental in the building of the Panama Canal, making eight trips here as Secretary of War, and then as President of the United States.”

In addition to Taft and Truman, U.S. Presidents Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, James E. Carter, and William Jefferson Clinton have stayed at the Little White House.

Key West is closer to Cuba than to most of Florida. John F. Kennedy spent time at the Little White House during a crucial period in U.S. history, when tensions with Cuba were at their height.

Kennedy first came to the Little White House in March 1961, just 23 days before the U.S. led invasion of Cuba known as the Bay of Pigs. “Russian missiles were discovered in Cuba, and Key West became an armed camp overnight,” Wolz says. “Tourism died, and even after the crisis passed, tourists did not return.” In November 1962, Kennedy visited Key West again, to demonstrate to potential tourists that it was safe to return to the island.

When the U.S. Navy switched from diesel submarines to nuclear submarines in 1974, the Naval Base at Key West was closed. The new nuclear subs were too large for Key West harbor. A private developer purchased the property following the base closure, and it sat unused and deteriorating for twelve years.

The house came under state ownership in 1987, thanks to the efforts of then Governor Bob Graham.

Since 1990, the Harry S. Truman Little White House has been open 365 days a year, offering guided tours. Details such as the magazines on coffee tables, the prints on walls, and glasses behind the bar, make walking through the Little White House like stepping back in time to 1949. Almost all of the articles in the home are genuine artifacts from the Truman presidency.

“Probably the most iconic items would be the president’s poker table that was made as a gift for him from the Navy cabinet shop, and also the president’s piano and presidential desk where he ran the country,” Wolz says. “These are important things that people seek out when they’re touring the house.”

The house itself is an authentic American artifact.

“Visitors, especially our international visitors, are always surprised at how homey and ordinary it is,” says Wolz. “It is not glitzy. It’s certainly not Washington, and it’s certainly not Versailles or any of the palaces that the rest of the world expects from their leadership.”

Dr. Ben Brotemarkle is executive director of the Florida Historical Society and host of the radio program “Florida Frontiers,” broadcast locally on 90.7 WMFE Thursday evenings at 6:30 and Sunday afternoons at 4:00, and on 89.5 WFIT Sunday mornings at 7:00. The show can be heard online at myfloridahistory.org.