Ever since 16th century Spanish explorers realized that Florida was a large peninsula, people have dreamed of finding or creating a “shortcut” linking the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico.

By the early 19th century, a series of politicians and businessmen envisioned cutting a canal from one side of Florida to the other, creating a direct path for commercial boat traffic across the top of the peninsula.

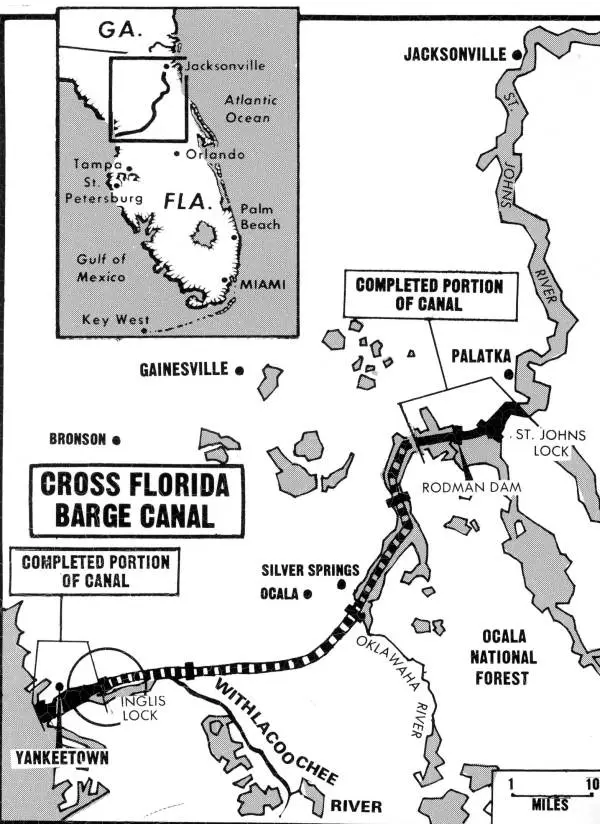

The Cross Florida Barge Canal would save three days of travel for ships if they didn’t have to go all the way around the peninsula, and could instead cut right through the middle of the state.

In 1935, the Army Corps of Engineers made plans for the Gulf Atlantic Ship Canal, a 30-foot deep waterway that would allow large vessels to cross the state through Ocala.

“As a result of a threat to the aquifer, issues of salt water intrusion, there will be a turn towards creating a barge canal, only 12-feet deep,” says David Tegeder, co-author of the book “Ditch of Dreams: The Cross Florida Barge Canal and the Struggle for Florida’s Future.”

Proponents of the Cross Florida Barge Canal planned a series of locks and dams that would allow a commercial waterway to be created from Jacksonville to Yankeetown, a community north of Tampa and west of Ocala.

With the Great Depression of the 1930s, construction began on the Cross Florida Barge Canal as a way to stimulate the economy and provide jobs. As part of his New Deal program, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved a five million dollar allocation of federal funds for the project.

“In September of 1935, 6,000 men are going to descend upon Ocala, Florida, and begin this construction,” says Tegeder. “Ocala is now a boomtown. There’s rapid growth. In one week the city issues ten liquor licenses as a measure of that optimism, and prosperity begins.”

Efforts to ensure that canal workers were being treated fairly were met with violence. In 1936, a labor organizer named George Timmerman came to Ocala to see that workers had reasonable compensation and safe working conditions.

“He is captured, roughed up, and found in the woods crucified, tied to a tree with his lips sewn shut, as a warning that labor activism will not be tolerated on the canal,” says Steven Noll, co-author of “Ditch of Dreams.” “After that, Mr. Timmerman disappears from the historical record.”

The African American community of Santos, about six miles south of Ocala, was decimated by the canal project.

“It is an African American community built around both Saturday night jook joints and Sunday afternoon churches,” says Noll. “It is wiped off the map in the 1930s by the canal. The canal is never built there, but the land is taken from these people either through eminent domain or purchased for pennies on the dollar, and the town is basically destroyed.”

Environmental concerns stalled completion of the canal for several decades. Federal funding allowed construction to resume in 1964, with President Lyndon Johnson presiding over the ground breaking ceremony. By this time, national defense had joined job creation as a rationale for building the Cross Florida Barge Canal.

“The national defense angle is that the canal will provide a sheltered waterway for protection, especially for oil tankers as they traverse the waters from the oil fields of Texas and Oklahoma to the refineries of New York,” says Noll. “They will not be able to be victims to the predatory operations of enemy submarines, whoever they might be.”

Marjorie Harris Carr led a group of environmentalists who successfully argued that the Ocklawaha River must be preserved and construction of the canal stopped. Their arguments were fueled by the use of a gigantic, destructive machine called “the Crusher,” that decimated Florida’s natural landscape.

“This thing could mow down six 80-foot cypress trees in one swath,” says Tegeder. “It basically cleared about an acre an hour.”

By the time President Richard Nixon halted construction of the canal in 1971, seventy-five million dollars had been spent on the project, and it was approximately 28 percent completed.

Today, the Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway provides hiking and biking trails on the remnants of the Cross Florida Barge Canal.