Florida Today 17

Florida Frontiers “The John H. Sams Homestead”

Ben Brotemarkle

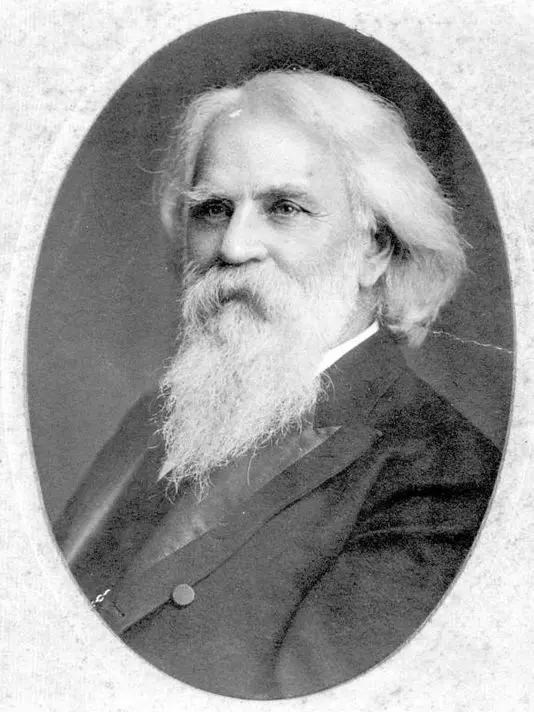

Life in Eau Gallie just wasn’t working out for John H. Sams and his family.

Sams and his wife Sarah had followed other family members from South Carolina to Eau Gallie, establishing their own homestead in 1875.

The 36 year-old Sams built a cabin for his wife and five children near the home of his cousins in the LaRoche family. For three years, Sams tried to establish a successful orange grove, but failed. He had no better luck with other crops he attempted to grow. In 1878, Sams decided to move his family to Merritt Island, because “it looked more like South Carolina.”

Sams didn’t just pack up his family’s belongings to make the move north. He packed up the entire house itself.

In November 1878, Sams dismantled his three-room cabin piece by piece, placed the sections of his home on a raft, and floated it up the Indian River to Merritt Island.

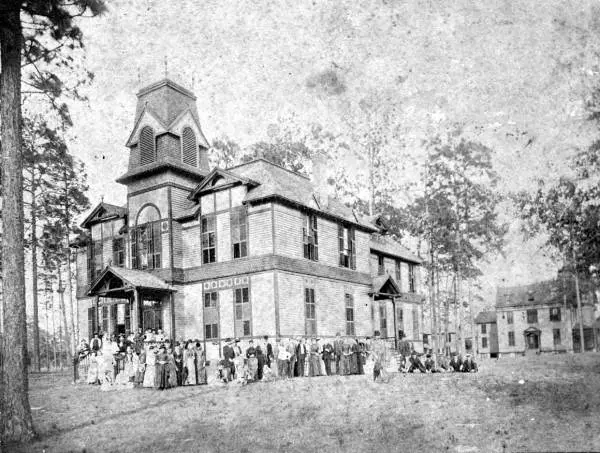

Today, the 1875 Sams Family Cabin serves as an education center in the 950-acre Pine Island Conservation Area, owned jointly by the Environmentally Endangered Lands (EEL) program and the St. Johns River Water Management District. Visit the property and you can still see the Roman numerals that Sams placed on sections of his cabin to help with reassembly.

Part of the education center features displays about the original inhabitants of the area. Archaeologists have found evidence of prehistoric human habitation on the property from about 5,000 BC to 2,500 AD. Ice Age fossils discovered on the property demonstrate that mammoths, mastodons, giant tortoises, and other large prehistoric animals lived and died there long before the Sams family arrived.

John H. Sams was a much more successful farmer on his new Merritt Island property. He and his LaRoche cousins thrived with their citrus, sugar cane, and pineapple crops. The family shared their prosperity with the community, which they named Courtenay after the mayor of Charleston, South Carolina.

The Sams family helped to establish St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Courtenay, a congregation that remains active today. Before the original church was built, services were held in the Sams cabin.

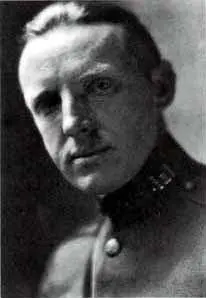

In 1880, John H. Sams was named the first Superintendent of Schools in Brevard County, adding to his stature in the community. Sams served as superintendent until 1920, while managing his agricultural business at the same time.

By 1888, Sams position in the community and his expanding family prompted him to build a new, two-story home. Perhaps because he had gone to so much effort bringing his cabin to Merritt Island from Eau Gallie, he constructed his new house directly adjacent to the original family home on the property.

The 1888 Sams family home has a wraparound porch, an office on the first floor where Sams kept track of his business interests and superintendent duties, a family room with a fireplace, three bedrooms upstairs, and a metal roof.

John H. Sams died in 1923 at the age of 84. Members of the Sams family lived on their Merritt Island property continuously from 1878 until 1996, when the land was purchased by the EEL program.

Today, visitors to the Sams Homestead at 6195 North Tropical Trail can enjoy learning about local history through the exhibits in the Sams Cabin Education Center and the 1888 Sams House. The 1875 cabin is the oldest standing home in Brevard County.

A roughly circular concrete path behind the cabin features outdoor exhibits that take visitors on a walk through time, from prehistory to the present. Trails winding throughout the property are available for hikers, cyclists, and nature lovers.

Earlier this month, teenager Ben Sams constructed and installed campfire benches and a bike rack at his great-great-grandfather’s homestead as part of his Eagle Scout project.

Life in Brevard County worked out well for the Sams family after all.

For more information on the John H. Sams Homestead and other local historic buildings, visit the Florida Preservation Blog by Lesa Lorusso at www.myfloridahistory.org.

Dr. Ben Brotemarkle is executive director of the Florida Historical Society and host of the radio program “Florida Frontiers,” broadcast locally on 90.7 WMFE Thursday evenings at 6:30 and Sunday afternoons at 4:00, and on 89.5 WFIT Sunday mornings at 7:00. The show can be heard online at myfloridahistory.org.