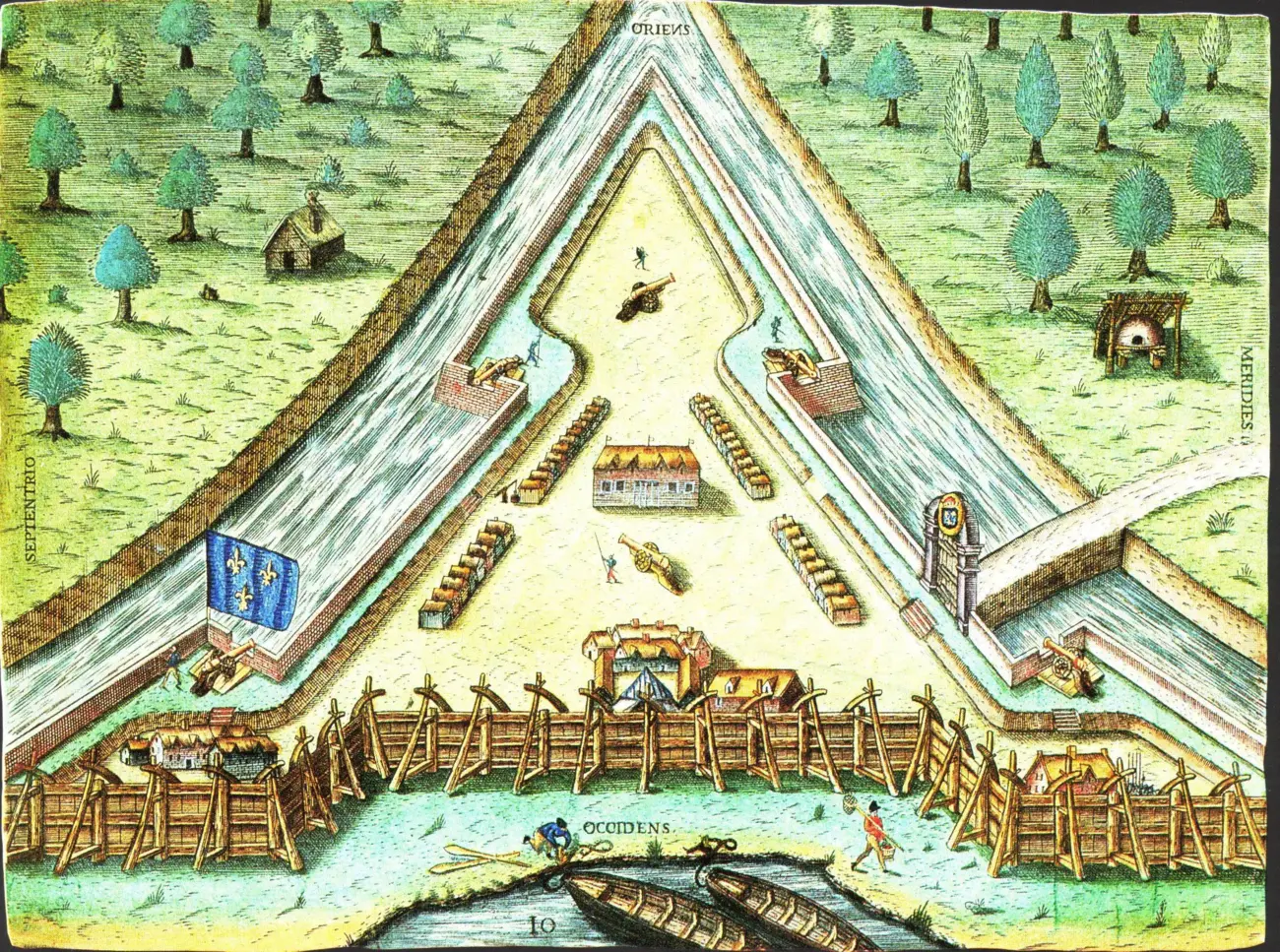

2014 marked the 450th anniversary of the French in Florida, recognizing the establishment of Fort Caroline in 1564.

2015 marks the 450th anniversary of the Spanish establishment of St. Augustine, the first permanent European settlement in North America.

The Spanish sent Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to Florida to wipe out the French Huguenots, and reclaim the land for Spain. Menéndez attacked Fort Caroline, killing everyone except the women and children, a group of musicians, and a few French soldiers who claimed to be Catholic. A hurricane helped the Spanish cause by sinking a fleet of French ships led by Jean Ribault.

Chuck Meide, director of the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program, spent the summer of 2014 searching for the lost fleet of Jean Ribault off the coast of Florida between Daytona Beach and Cape Canaveral, and will continue those efforts in the summer of 2015.

“I’m a Jacksonville native,” says Meide. “I grew up hearing the stories about Ribault and the French at Fort Caroline, and Menéndez and the Spanish in St. Augustine. It’s our national origin story. It’s how the first settlement here in the present-day United States happened. So it’s very exciting that we’re in a position to find these ships.”

Menéndez and his men arrived near the Timucuan village of Saloy on September 8, 1565, where they established St. Augustine. Ribault had arrived with a fleet of seven supply ships just days prior to restock Fort Caroline, near present-day Jacksonville. Ribault decided to launch a preemptive strike against the Spanish and his four largest ships set sail for St. Augustine on September 10.

Before Ribault’s ships could even attempt to navigate the dangerous inlet at St. Augustine, an unexpected hurricane forced the ships further south, where they wrecked off the coast between Daytona Beach and Cape Canaveral.

“Those ships are out there,” Meide says. “Menéndez wrote a letter to the King (Philip II of Spain) giving at least a description of the locations of La Trinité and the other three French wrecks. We also have a clue from an archaeological site known as the Armstrong Site that was found by relic hunters in 1970 and ’71.”

Meide says the relic hunters found French coins, iron spikes, tools, and other shipwrecked material.

“The archaeologists from the National Park Service who followed up with excavations in the 1990s agreed with the relic hunters that this appears to be the survivor camps of the 1565 shipwrecks. It seems to me the logical place to search for the shipwrecks is near where the survivors were.”

During the same hurricane that sunk Ribault’s fleet, Menéndez and his men spent two days marching from St. Augustine to Fort Caroline. After capturing the French enclave, the Spanish executed 145 shipwreck survivors, including Jean Ribault. Before being put to death, the French were given the opportunity to renounce their Protestant faith and accept Catholicism. All but a few refused.

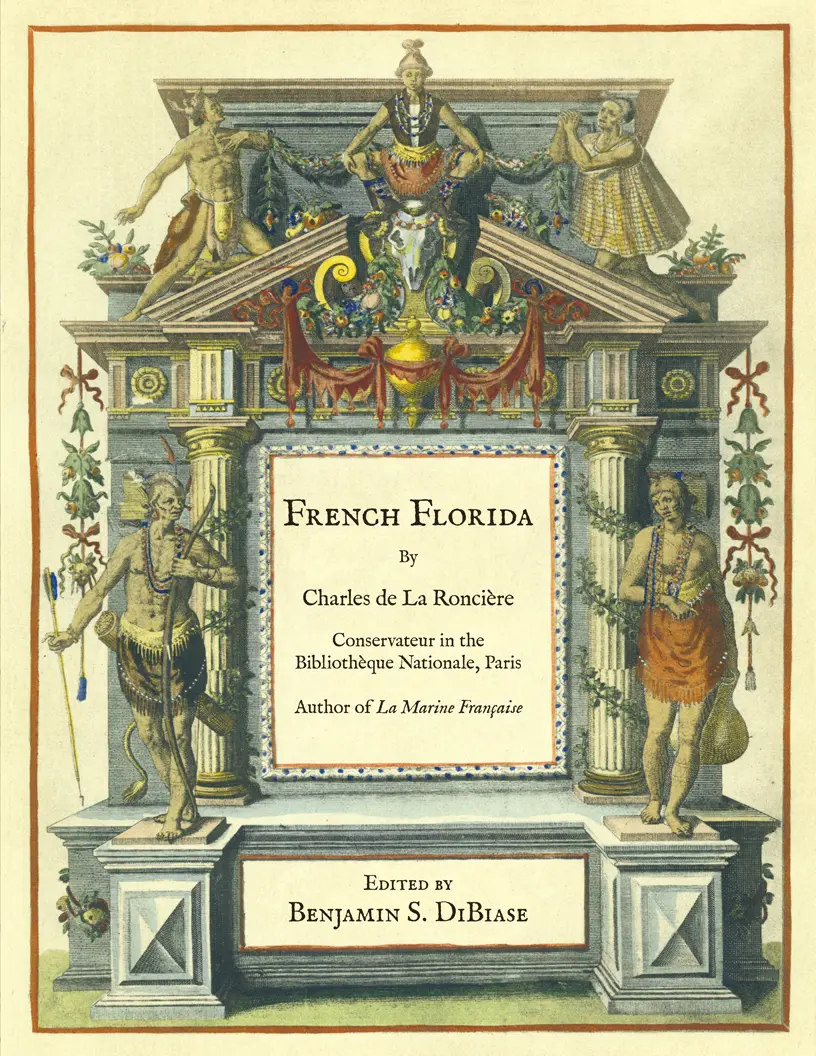

Original sixteenth century French and Spanish documents describing the establishment and destruction of Fort Caroline are few, and good English translations of those documents are rare. The Florida Historical Society Press has published the first English translation of French Florida: A Narrative Based on the Earliest Accounts of the French Presence in Florida by Charles de La Roncière.

“In this book he included a few word-for-word translations of those original documents, and that’s what’s really important,” says Benjamin S. DiBiase, editor of the book. “There are very few of these documents that have been translated in their entirety into English, for English speaking scholars to utilize.”

The book French Florida was originally prepared for publication in the late 1920s, but was never printed. After traveling around the state with the Florida Historical Society for about 70 years, the manuscript sat on the shelves at the Library of Florida History in Cocoa for another 17 years until it was rediscovered by DiBiase.

“With a keen eye we can parse out a lot of details from this narrative, and from the contemporary Spanish narratives of the attack on Fort Caroline and the establishment of St. Augustine, and through these sources get a little closer to what happened.”

Milestone anniversaries provide inspiration to reexamine these stories.

Dr. Ben Brotemarkle is executive director of the Florida Historical Society and host of the radio program “Florida Frontiers,” broadcast locally on 90.7 WMFE Thursday evenings at 6:30 and Sunday afternoons at 4:00, and on 89.5 WFIT Sunday mornings at 7:00. The show can be heard online at myfloridahistory.org.