This week the nation is remembering a series of three marches in support of voting rights that took place fifty years ago. Peaceful protesters in Florida’s neighboring state of Alabama were attacked by police.

The demonstrations encouraged President Lyndon Johnson to sign the Voting Rights Act.

Less than a year earlier, demonstrations in Florida helped lead Johnson to signing the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964.

In St. Augustine, attempts by protesters to peacefully demonstrate for civil rights were also met with threats and violence.

“I’m history. I was there,” says Barbara Vickers, who was 41 in the summer of 1964.

The night of greatest violence came on June 25, 1964, when peaceful demonstrators, both black and white, were attacked with bricks and stones.

“We used to march down from the different churches, and we had night marches. The night that they beat Andy Young on the corner there, I was there that night,” says Vickers. “We couldn’t come in the plaza because they had rocks ready for us, so we had to march around the plaza. The bricks came flying here and there. A lot of people got hurt that night, but I didn’t get hit.”

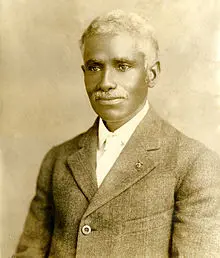

Vickers lived across the street from African American dentist and air force veteran Dr. Robert B. Hayling, who was the organizer of the local civil rights movement in St. Augustine. Young men had to patrol her street every night to defend Dr. Hayling from attacks by the Ku Klux Klan.

As demonstrations became more frequent and violence against the protesters increased, Martin Luther King Jr. came to St Augustine to help organize the effort. It was King who encouraged Vickers to join the movement and participate in peaceful protests.

“Dr. King came. He looked at me and said ‘Young lady, will you go?’ There was something about his eyes that was electrifying to me and before I knew it I said yes.”

King and his followers were known for their strategy of encouraging social change through non-violence, even in the face of police harassment and intimidation. St. Augustine was the only Florida city where King was arrested.

“After the meetings, we had to drive back to our homes, and I was stopped many times going home,” Vickers says.

“They searched my car and they found the crank for the tire, and the police said I had a weapon. They said ‘I could arrest you for this.’ They were doing all this to intimidate us and discourage us from going to the meetings. Nothing kept me from going to the meetings.”

As demonstrations reached their peak in St. Augustine, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was being filibustered in congress. The images of segregation and violence coming out of the city helped to end the stalemate and get the legislation passed.

Decades later, Vickers felt that the everyday people of St. Augustine who helped to move civil rights forward for all Americans needed to be recognized. She formed the St. Augustine Foot Soldiers Remembrance Project, which raised funds for a monument.

In May 2011, the St. Augustine Foot Soldiers Monument was unveiled in the downtown plaza where demonstrators had been attacked.

The bronze sculpture is facing away from the slave market where black people were bought and sold as property, and toward the building where the first attempts occurred to integrate drug store food counters in the city.

“It’s not a depressing subject, it’s an enlightening subject,” says sculptor Brian R. Owens. “The Civil Rights Movement confirmed that we have what it takes to survive the childhood of our species, that we have the tools at our disposal that we need to solve our problems.”

The monument designed by Owens includes four bronze busts in front of a relief sculpture. Each of the people depicted represents many others who fought for equality in St. Augustine. They include a white male college student, a black male in his 30s, a black woman in her 60s, and a black teenage girl.

Black people helped build St. Augustine in 1565, but were left out of the city’s 400th anniversary celebration in 1965. Times have changed for this year’s 450th anniversary.

“We were left out the last time, but not this time,” says Vickers.

Dr. Ben Brotemarkle is executive director of the Florida Historical Society and host of the radio program “Florida Frontiers,” broadcast locally on 90.7 WMFE Thursday evenings at 6:30 and Sunday afternoons at 4:00, and on 89.5 WFIT Sunday mornings at 7:00. The show can be heard online at myfloridahistory.org.