Every Fourth of July, Floridians celebrate Independence Day with cookouts, hometown parades, and of course, fireworks as America’s victory over the British in the American Revolution is commemorated.

Not all American colonists supported the war, though. Many remained dedicated to King George III and England. As the American Revolution progressed, these Loyalists became refugees and were forced to flee the colonies.

From 1763 to 1783, Florida remained under British control; so many Loyalists came here from the American colonies to the north.

On December 17, 1782, as the end of the American Revolution approached, 16 ships left Charleston, South Carolina bound for the Loyalist port of St. Augustine, Florida. The ships carried hundreds of people, civilian as well as military.

Just before the ships could make port in St. Augustine, all 16 were lost on December 31, 1782.

Chuck Meide, director of the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP), was determined to find the Loyalist ships that were lost off the coast of St. Augustine in a violent New Year’s Eve storm.

“The first step is really to try to look at the old historic maps and figure out how the landscape has changed,” Meide says, adding that the St. Augustine inlet “was very notorious for being dangerous for ships and for changing a lot. Every time a storm would come, the channels would shift around. That’s why we have so many shipwrecks, because of the shoals.”

Today, modern engineering keeps the inlet in place, but historic maps show how the location of the inlet has shifted over time. Meide determined that in the late 1700s, the inlet was about 3 miles south of its present location. That’s where he decided to look for the Loyalist shipwrecks.

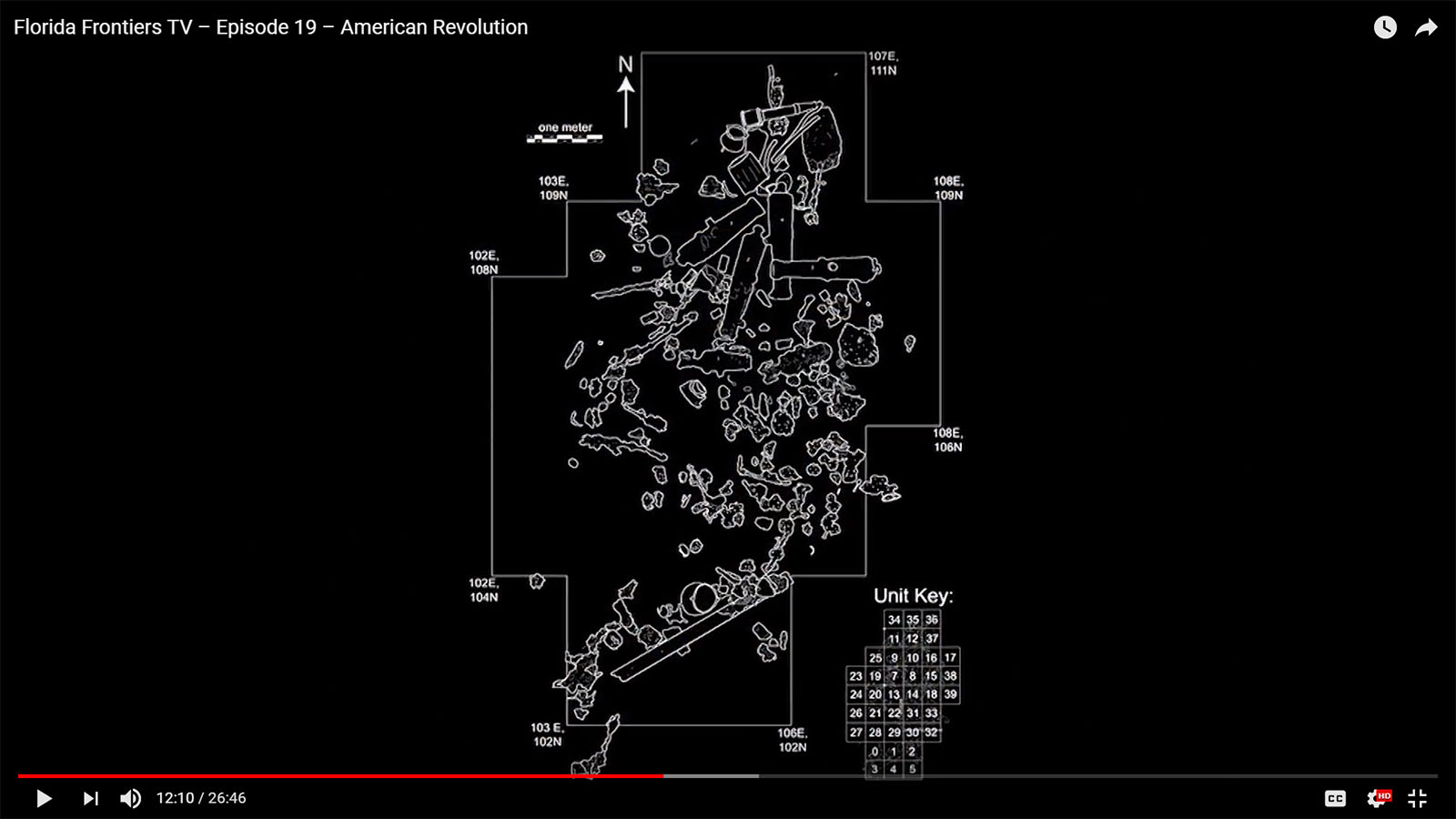

Meide and his team used high-tech equipment such as a magnetometer to search for objects made of metal, and a side-scan sonar that produces an acoustic image of the ocean floor.

“Basically, it’s like we’re mowing the lawn,” Meide says. “We’re going back and forth and covering an area that we feel is high probability to find shipwreck sites, and it works.”

When the equipment indicated that a shipwreck might be located at a particular spot, it was time for Chuck Meide to go diving. He says the conditions were difficult to work in because it was “black as midnight down there” and communication with the other archaeologists was impossible. “Imagine if you were doing archaeology on land, gagged and blindfolded.”

Chuck Meide was working alone in the dark water when he made the first discovery of the expedition. The magnetometer had indicated the presence of metal, so Meide was working with a ten foot pipe jetting water to clear away sand. At first he didn’t feel anything unusual. After a few times sinking the pipe “to the hilt,” Meide hit something hard.

In quick succession, Meide uncovered ballast stones that were common in colonial era sailing ships, an unidentifiable man-made iron object, and a wooden plank.

“Now my heart’s beating pretty fast,” Meide says. “The next thing I found really sealed the deal. It was another large, concreted object. It was round, it was hollow. I felt a rim and could feel inside and I realized we had a big cooking pot or a cauldron. I even felt one of the three legs on the bottom. So that suggested colonial shipwreck.”

That first series of discoveries was in August 2009, and the excavation has continued every summer since.

Subsequent discoveries helped to confirm that the shipwreck was from the colonial period, from the late 1800s, and more specifically that it was carrying British Loyalists. Meide’s team uncovered lead shot, buckles, buttons, a wine glass base, and other objects.

Perhaps the most definitive artifact found was a canon marked with the year 1780.

When the American Revolution ended in 1783, the British period was over and Florida once again became property of the Spanish. Florida became an American Territory in 1821, and was named a state in 1845.

As citizens of the United States, Floridians would celebrate Independence Day until 1861, when the state seceded from the Union. After Florida became part of the United States again in 1868, Fourth of July celebrations resumed and continue today.

Dr. Ben Brotemarkle is executive director of the Florida Historical Society and host of the radio program “Florida Frontiers,” broadcast locally on 90.7 WMFE Thursday evenings at 6:30 and Sunday afternoons at 4:00, and on 89.5 WFIT Sunday mornings at 7:00. The show can be heard online at myfloridahistory.org.

Photo caption info: Underwater archaeologist Chuck Meide excavates a 1780 canon from a British Loyalist shipwreck off the coast of St. Augustine.