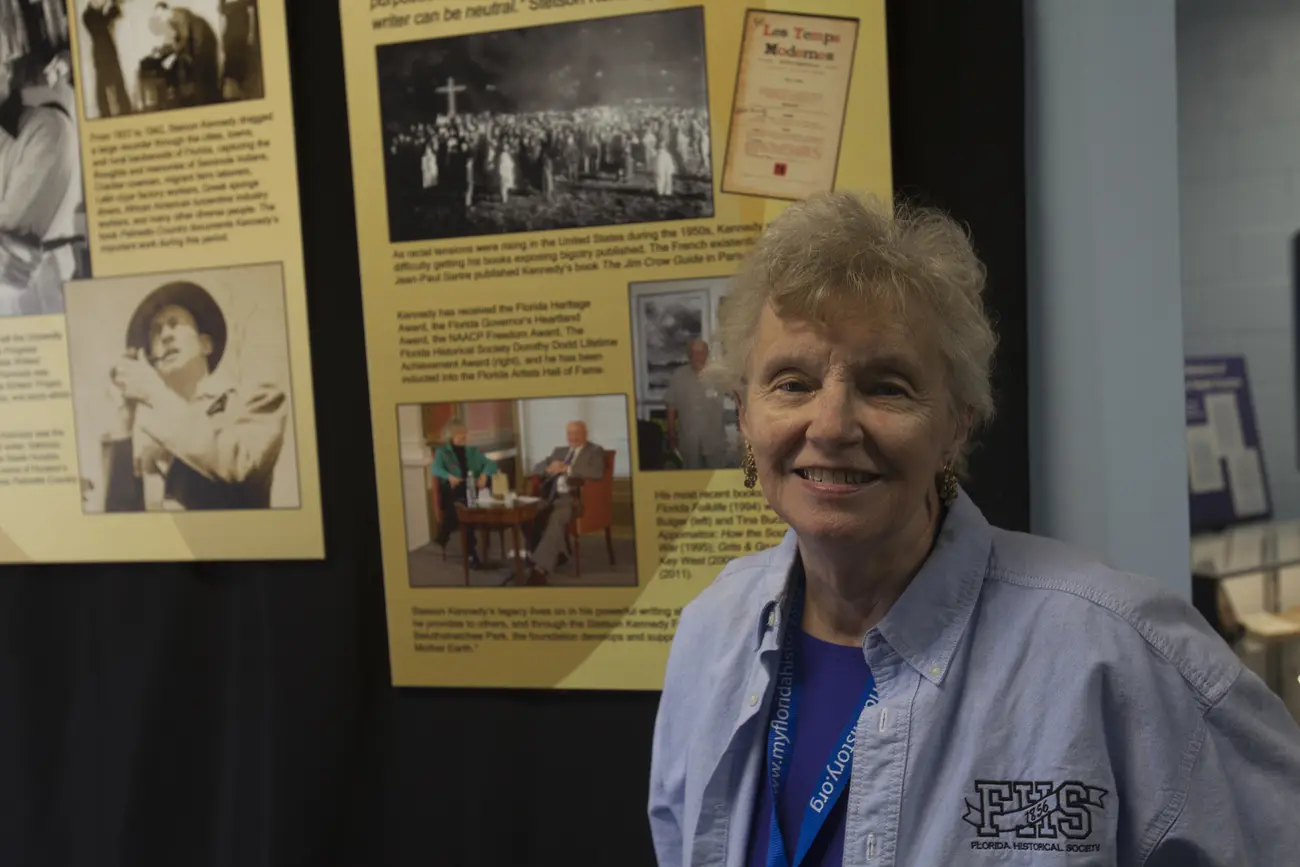

The third and final presentation in the “Second Saturdays with Stetson Series” is Saturday, March 11, at 2:00 pm, at the Brevard Museum of History and Natural Science, 2201 Michigan Avenue, Cocoa. The free talk, presented in conjunction with the temporary exhibition “Stetson Kennedy’s Multicultural Florida” will feature Kennedy’s widow, author and educator Sandra Parks.

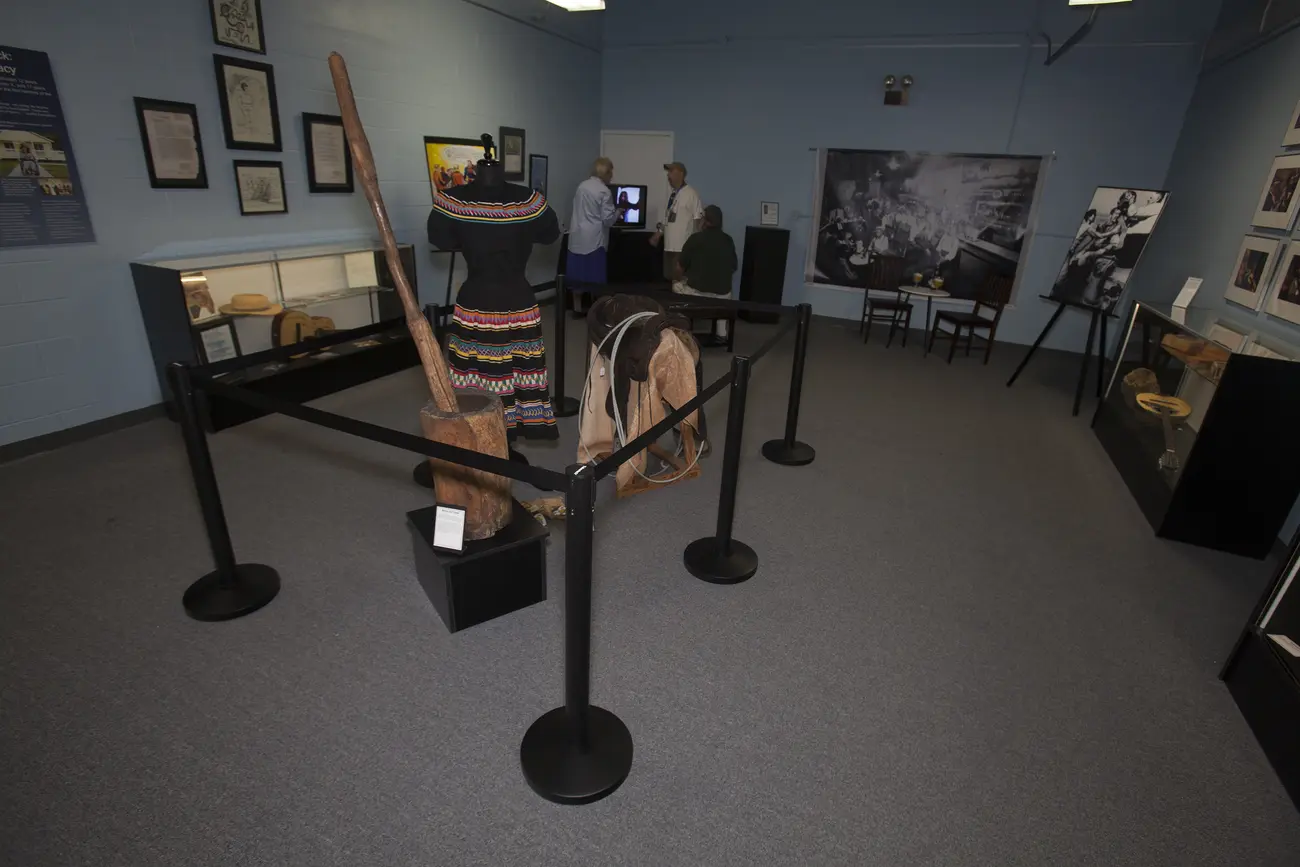

The items on display in the exhibition “Stetson Kennedy’s Multicultural Florida” include artifacts and images reflecting the diverse Florida communities that folklorist, author, and activist Stetson Kennedy documented throughout the state in the 1930s and ‘40s. Kennedy interviewed Greek sponge divers in Tarpon Springs, Latin cigar rollers in Ybor City and Key West, African American turpentine industry workers, Cracker cowmen, Seminole Indians, and many others.

Also on display are personal items such as Kennedy’s hat, his typewriter, and a letter he received from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

In the 1940s and ‘50s, Kennedy infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan, exposing their secret activities. He continued fighting for equal rights for all people until his death in 2011.

The note from Dr. King, on letterhead from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, is dated November 3, 1965. In the letter, King thanks Kennedy for his work in “our struggle for racial justice,” and his “great moral support, not only to myself, but to our entire staff.” King goes on to tell Kennedy that, “You have my heartfelt appreciation for such a worthwhile contribution to the Freedom Movement.”

Visitors to the Brevard Museum are fortunate to be able to see the letter.

“About a month before Stetson died, I asked him ‘where did you put the letter from Dr. Martin Luther King?’” says Parks. “I had begged him for the eight years we were together to please put it in the safety deposit box, and he would never do that. About a month before he died, he pointed to his legal documents file and said, ‘it’s in there.’”

A few days after Kennedy died, Parks began the daunting task of going through stacks of unorganized papers that her husband had saved. She started with the box that was supposed to contain the letter from Dr. King. The letter was not there.

“I had two other people go through the box, just in case I could have missed it,” says Parks. “Somewhere in with the takeout menus and the old phone bills there was a letter from Dr. Martin Luther King we hadn’t found yet.”

The letter was eventually discovered among copies of various newspaper articles, several drafts of an unpublished autobiography, and other personal correspondence.

“People think that this is some kind of scholarly exercise, but it is an endeavor for patience,” Parks says.

Eventually, Parks had fifteen years of accumulated papers sent to the University of Florida to be sorted and archived. That collection is being merged with papers already archived at the University of South Florida.

“In 1996, Stetson sold his then papers to the University of South Florida, along with many of his foreign language edition books that are quite rare and things we cannot find anymore,” says Parks.

Some foreign language editions of Kennedy’s books are currently on display at the Brevard Museum.

The entire collection of Kennedy’s papers is now under one roof at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

“Stetson had been a student at the University of Florida,” says Parks. “He and Sam Proctor, who started the oral history center there, were friends years ago, back when they were both college boys. Most significantly, the WPA papers are there, papers of Zora Hurston’s are there, papers of Marjorie Rawlings are there.”

Kennedy was a pioneer of oral history, had worked for the WPA Florida Writers Project, was supervisor of author Zora Neale Hurston for a time, and took a class at UF from Pulitzer Prize winner Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings.

“Stetson had hoped that his papers would go to the University of Florida,” says Parks.

The Florida Historical Society, which operates the Brevard Museum of History and Natural Science, assembled the exhibition “Stetson Kennedy’s Multicultural Florida” with the assistance of Sandra Parks, the University of Florida, the Florida State Archives, and private collectors.

The Brevard Museum will display the exhibition through May.