As innocent four-year-old girls in the late 1940s, Katie, who is white, and Delia, an African-American, become best friends despite societal pressures against them. In 1960, when the girls are 16, Kate abandons her childhood friend when she is needed most. In 2006, Kate is working to earn Delia’s forgiveness as danger surrounds the women’s reunion.

That’s the premise of the new novel “Reparation” by Titusville author Ruth Rodgers. Although the exciting and suspenseful book is not based on specific actual events, it does reflect reality in Florida from the 1940s to the present.

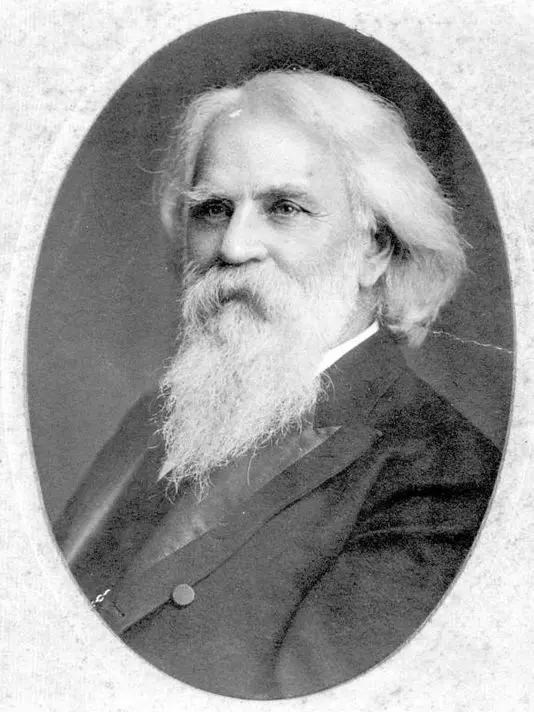

Ruth Rodgers is a native Floridian, raised on a farm in Madison County. She grew up in rural north Florida in the 1950s and ‘60s, when schools, theaters, restaurants, and other public accommodations were racially segregated. Rodgers says that black families and white families worked side by side in the tobacco fields, but that’s where the interaction ended.

“We worked with black people, but we never socialized with them,” Rodgers says. “It was very much frowned upon.”

The novel “Reparation” is written from the first-person perspective of Kate as she flashes back through her childhood relationship with Delia. The reader sees Kate’s convictions about racial equality strengthen over time. Rodgers is the same age as her main character Kate, and shares other traits with her. Both believed in racial equality, but were not outspoken about their views in the 1960s.

“They were not popular views at that time,” Rodgers says. “I think, looking back, a lot of liberal Southerners feel a sense of guilt that we didn’t do more, that we kept our views to ourselves, and that we let culture dictate to us how to behave.”

The novel “Reparation” has a warning label on the cover informing readers that the offensive and racially charged “n-word” appears in the book. Use of the word is particularly jarring to modern readers when it comes from four-year-old Katie near the beginning of the story. While presented in an historically accurate context, its use may be too shocking for sensitive readers.

“She wouldn’t have had any other word to use,” Rodgers explains. “This was the word that her parents used, her grandparents used, her neighbors used, everybody around her used. It was very common in the area in which I grew up. To her it’s just a descriptive term. It’s not a derogatory term, because she has no other word to replace it with.”

“Reparation” was being prepared for publication just as discussions about race relations in Florida and the nation were reigniting. As design of the book was nearing completion in 2013, President Obama spoke about frustration over the verdict in the Trayvon Martin case; the Supreme Court weakened the Voting Rights Act, and celebrity chef Paula Deen’s career was damaged by her admitted use of the “n-word.” Speakers at the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington encouraged people to be diligent about protecting the legacy of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

Rodgers says that a need exists for continued discussion about the history of race relations in Florida and the nation. She believes that her novel “Reparation” can serve as a catalyst for such conversations. “We’ve come a long way since the 1940s,” Rodgers says, “but we still have a long way to go.”

The story of Katie and Delia demonstrates that racism and bigotry are learned behaviors that can be overcome, even when they are instilled in children at a very young age and supported by prevailing societal attitudes.

Beyond providing a particular perspective on racial attitudes in Florida and how they evolved in the last half of the twentieth century, this novel also offers a well written and suspenseful story.