On Christmas night 1951, a bomb exploded under the Mims home of educator and civil rights activist Harry T. Moore. The blast was so loud it could be heard several miles away in Titusville.

Moore died while being transported to Sanford, the closest place where a black man could be hospitalized. His wife Harriette died nine days later from injuries sustained in the blast.

The couple celebrated their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary on the day of the explosion, and Harriette lived just long enough to see her husband buried.

The Moore’s daughter, Juanita Evangeline Moore, was working in Washington, D.C. in 1951, and was scheduled to come home for the holidays on December 27th, aboard a train called the Silver Meteor. She did not hear the news about her family home being bombed until she arrived.

“When I got off the train in Titusville, I knew something was very, very wrong,” Moore said in an interview before her death in October 2015. “I had not turned on radio or television, so I didn’t know a thing about it until I got off the train. I noticed that my mother and father were not in front of all my relatives to greet me and they were always there.”

Moore was given the news by her Uncle George, who was home on leave from Korea.

“We got into his car and got settled, and the first thing I asked was ‘Well, where’s Mom and Dad?’ No one said anything for a while, it was complete silence. Finally, Uncle George turned around and he said ‘Well, Van, I guess I’m the one who has to tell you. Your house was bombed Christmas night. Your Dad is dead and your Mother is in the hospital.’ That’s the way I found out,” said Moore.

“I’ve never gotten over it. It was unbelievable.”

Moore insisted on being taken to her parent’s home. The blast had done extensive damage. She saw a huge hole in the floor of her parent’s room, into which their broken bed had collapsed. Wooden beams had fallen from the ceiling. Shards of broken glass covered the bed in the room she shared with her sister, Peaches.

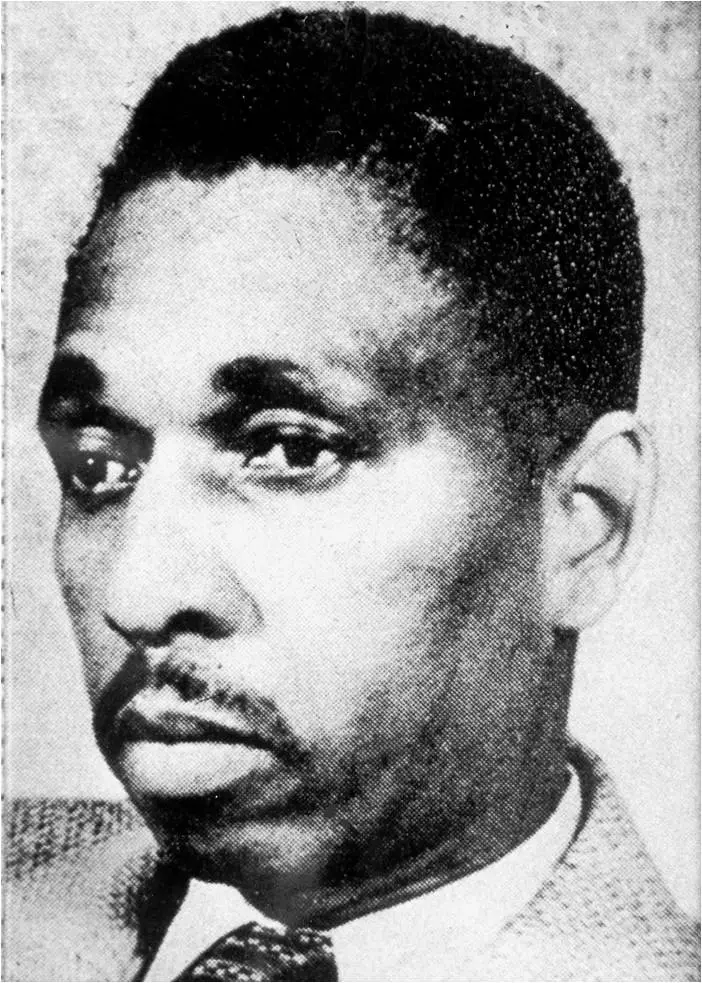

Harry T. Moore was born November 18, 1905, in Houston, Florida, located in Suwannee County. At age 19, Moore graduated with a high school diploma from Florida Memorial College where he was a straight-A student, except for a B+ in French. Other students called him “Doc” because he did so well in all of his classes.

Moore moved to Mims in 1925 after being offered a job to teach fourth grade at the “colored school” in Cocoa. He met Harriette Vida Sims. They married and had two daughters. Moore, his wife, and both of their daughters graduated from Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona.

As a ninth grade teacher and principal at Titusville Negro School, Moore instilled in his students a sense of pride and a solid work ethic. A popular and skilled educator, Moore was fired for attempting to equalize pay for African American teachers in Brevard County.

Moore led a highly successful effort to expand black voter registration throughout the state, dramatically increased membership in the Florida branch of the NAACP, worked for equal justice for African Americans, and actively sought punishment for those who committed crimes against them.

“I do remember a lot of NAACP work with my Dad from the time I was able to understand what was going on,” said Juanita Evangeline Moore. “I helped him a lot with his mailing lists. We had a one-hand operated ditto machine. He usually typed out the stencil and he ran off whatever material he wanted to send out.”

Although the murders of Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore have never been solved, it is believed that members of the Ku Klux Klan from Apopka and Orlando planted the bomb on Christmas night.

Moore and his wife were killed 12 years before Medgar Evers, 14 years before Malcolm X, and 17 years before Martin Luther King, Jr., making them the first martyrs of the contemporary civil rights movement.

The Moore Cultural Complex in Mims features a civil rights museum and a replica of the Moore family home.