There is a road in downtown Orlando called Division Street. It has traditionally been the dividing line between the predominately white community to the east, and the African American community to the west.

As downtown Orlando was established in the late 1800s, a separate but parallel black community emerged. By the early twentieth century, the Parramore neighborhood included several blocks of prosperous black owned businesses including a tailor shop, a theater, and attorney’s offices. There were African American physicians, dentists, photographers, and other professional people. Churches were integral to the community.

In 1929, a prominent black physician named William Monroe Wells opened the Wells’Built Hotel on South Street.

“He came here in 1917 from Fort Gaines, Georgia, and records show that by 1921 he was listed in city directories as a physician and owner of a ‘notions’ store, and by 1926 he obtained a permit from the City of Orlando to build a hotel,” says former Florida State Senator Geraldine F. Thompson, founder of the Association to Preserve African American Society, History, and Tradition (PAST, Inc.) “During that time, when African Americans visited the Central Florida area, they did not have lodging available to them at any of the major hotels in the area because of segregation.”

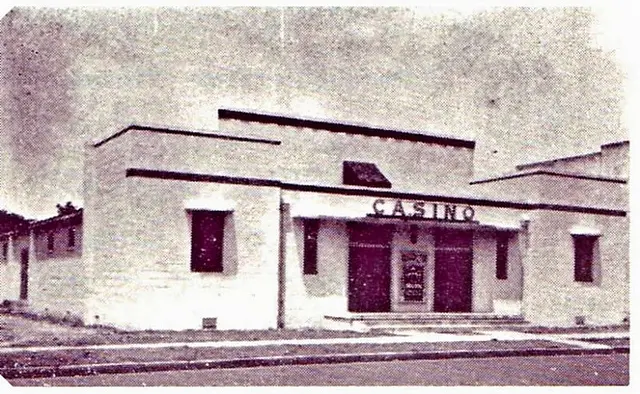

Directly next door to the Wells’Built Hotel, Dr. Wells built the South Street Casino. This was not a gambling establishment, but a community center. There was a basketball court inside, and people held graduations, wedding receptions, and other gatherings at the venue.

Today, the Amway Center on South Street hosts popular musical acts. In the mid-twentieth century, it was the much smaller South Street Casino that brought well known African American performers to the area. Musicians including Erskine Hawkins, Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles, B.B. King, and many others would perform at the South Street Casino and stay next door at the Wells’Built Hotel.

Legendary drummer David “Panama” Francis played in the South Street Casino many times. Francis was born in Miami in 1918, and was playing in nightclubs by age 13. Shortly after arriving in New York in 1938, Francis played with Lucky Millinder’s Orchestra for six years at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem. He played and recorded with many great artists of the day, including Duke Ellington, John Lee Hooker, James Brown, Buddy Holly, the Four Seasons, and the Platters.

Before his death in 2001, Francis remembered playing in the South Street Casino.

“I played there about twice a year,” Francis said. “The old timers remember the band that used to come up from Miami, George Kelley’s band. That place was so hot. Until, I mean the perspiration was all down in my shoe. I could hear when I walked, I’d hear the squish, squish, squish of the water that was in there ‘cause, you know, there was no air conditioning or nothing like that. And it’d be packed.”

The South Street Casino had a creative marketing strategy to entice people to attend the Saturday night dances there.

“Back then, you know, there was no radio and TV and all that, so what happened—if the dance would, say, start at nine o’clock, they’d let all of the people in [earlier] for free to listen to the band, and you’d play about half an hour of music,” said Francis. “All of the good dancers would be standing around—who, you know, were the critics. If they gave the nod that, you know, that the band is all right, they’d let all of the people out—and then they had to pay to come in and hear the band. So that’s how they used to do. A lot of times they would get on a truck and ballyhoo.”

In the second half of the twentieth century, the Parramore neighborhood entered a period of economic and social decline. The South Street Casino burned down in 1987, and the Wells’Built Hotel was abandoned and threatened with demolition.

In 2001, the building was refurbished by the Association to Preserve African American Society, History and Tradition, and transformed into the Wells’Built Museum of African American History and Culture. The museum is part of a larger effort to improve and revitalize the Parramore neighborhood.