“Come in, and welcome to my home,” says an animatronic version of John G. Riley, talking to students at the Riley House Museum. The life-sized robotic figure speaks from behind Riley’s desk, hands gesturing, mouth moving, and eyes blinking as he tells visitors about Florida history.

“I was just catching up on my passion, reading. You know there was a time when a man like me was not allowed to read. You see, I was born into slavery on September 24th, 1857, right here in Tallahassee.”

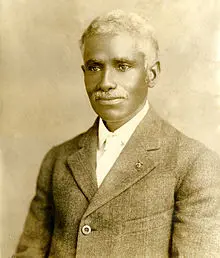

John G. Riley was an educator and entrepreneur in Tallahassee’s African American community.

“He lived to 1954, so he was 97 years of age,” says Althemese Barnes, founder and executive director of the Riley House Museum. “He lived to experience much change in those 97 years. After slavery, he chose to go into education. Of course, during slavery he was denied the opportunity to read and write, but he learned from some of his relatives who were literate.”

Riley became principal of Lincoln Academy, the first African American school in Leon County that offered a secondary program. He served as principal for 33 years, from 1893 to 1926. During that time he also acquired a significant amount of real estate in downtown Tallahassee.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Smokey Hollow was a thriving African American community with black owned businesses, schools, and churches. Smokey Hollow was destroyed through the use of eminent domain in the 1960s.

Riley’s home, now a house museum, is the only existing structure that remains from Smokey Hollow.

“During its existence, that was the time of legal segregation, so there were very independent black communities that evolved out of a necessity to survive,” says Barnes.

“When blacks came out of slavery, there was a great passion for religion and education. So usually in most of these black independent communities, you would find a school and churches, and usually a cemetery attached to the church. So you had these enclaves where blacks lived and relied a lot upon each other to deal with the social issues of hostility and injustices and inequality that existed.”

Like all of the other structures in the Smokey Hollow community, the Riley House was threatened with demolition, but because of its particular historical significance, it managed to escape the wrecking ball.

Restoration of the home began in the 1970s, and it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. The building opened as a house museum in the mid-1990s.

“The house was almost lost,” says Barnes. “The city bought it for back taxes and the plan was to demolish it and erect an electric substation on this site. Some local citizens who knew all that Mr. Riley had contributed decided that shouldn’t be.”

Funds were raised to purchase and refurbish the house, with the first restoration completed in 1981. The home was preserved but underutilized for 15 years.

“The people who saved the house didn’t live long enough to do the second thing that they wanted to have happen, which was for it to be a museum to preserve African American history and promote history,” says Barnes. “When I retired, I decided to make this my philanthropic effort, and we started the museum in January of 1996.”

Built in 1890, The John G. Riley House Museum is a two-story wood frame building on brick piers, with a gable roof and a brick chimney. In addition to period furniture from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the museum has rotating gallery space and an adjacent building for public presentations.

The goal of the museum is to educate all people about African American history and culture, and John G. Riley’s contributions.

“One of my most important involvements, next to my job as principal and my church work at St. James CME,” says the Riley robot, “is working with Booker T. Washington and the Negro Business League throughout Florida to advocate racial uplift through economics and education, and promote racial harmony.”

The John G. Riley House Museum is located at 419 East Jefferson Street in Tallahassee. Hours are Monday through Thursday, 10am to 4pm, Friday and Saturday, 10am to 2pm, and by appointment.

Dr. Ben Brotemarkle is executive director of the Florida Historical Society and host of the radio program “Florida Frontiers,” broadcast locally on 90.7 WMFE Thursday evenings at 6:30 and Sunday afternoons at 4:00, and on 89.5 WFIT Sunday mornings at 7:00. The show can be heard online at myfloridahistory.org.