More than 200 white people wielding baseball bats and ax handles chased African Americans through the streets of downtown Jacksonville, trying to beat them into submission.

It was August 27, 1960, a day that became known as “Ax Handle Saturday.”

The violent attack was in response to peaceful lunch counter demonstrations organized by the Jacksonville Youth Council of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

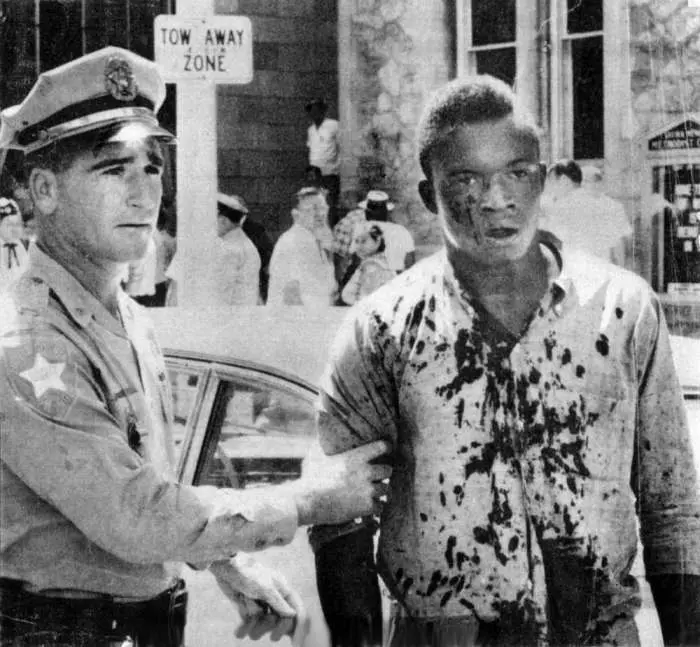

The attack began with white people spitting on the protestors and yelling racial slurs at them. When the young demonstrators held their resolve, they were beaten with wooden handles that had not yet had metal ax heads attached.

While the violence was first aimed at the lunch counter demonstrators, it quickly escalated to include any African American in sight of the white mob. Police stood idly by watching the beatings until members of a black street gang called “The Boomerangs” attempted to protect those being attacked. At that point police night sticks joined the baseball bats and ax handles.

Bloodied and battered victims of the vicious beatings fled to a nearby church where they sought refuge and comfort from prayer and song. Eventually the white mob dispersed.

Sixteen-year-old Rodney L. Hurst was president of the Jacksonville Youth Council, leading sit-ins at “whites only” lunch counters in Woolworth’s and W.J. Grant Department Store to protest racial segregation.

Hurst has written about his experiences in the award-winning book “It was Never about a Hot Dog and a Coke.”

History teacher Rutledge Pearson inspired Hurst to become involved in the civil rights movement at a very early age. Hurst says that Pearson was an innovative teacher who facilitated interactive classes. “As we talked about American history and as he gave us his insights, he would tell us ‘freedom is not free, and if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.’ He would encourage us to join the Youth Council NAACP, which we did.”

Today, Rutledge H. Pearson Elementary School in Jacksonville bears the name of the teacher who influenced many young people to become leaders in the African American community.

In 1959, the year before Ax Handle Saturday, Nathan B. Forrest High School opened in Jacksonville, celebrating the memory of the first Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. As of July 1, 2014, the name has been changed to Westside High School.

The violence of Ax Handle Saturday did not occur in a vacuum. Racial segregation and overt racism had been building tension in Jacksonville for decades. In his book, Hurst places his personal story as a young activist into the larger historical context of the civil rights movement. “Jacksonville was a mess, not unlike a lot of other southern cities,” Hurst says.

It is believed that the Ku Klux Klan organized the violence of Ax Handle Saturday. “The intent was to scare, intimidate, and bring physical harm,” Hurst says. “Many times you could not draw a line between the Klan and law enforcement, because law enforcement were at least accomplices to a lot of the things the Klan did.”

While the events of Ax Handle Saturday were documented in Life Magazine and newspapers from major cities across the country, reporters from the Jacksonville Times-Union and the Jacksonville Journal were not allowed to cover the story.

Some people in the city are now more willing to explore its painful past.

In 2010, the University of North Florida opened the exhibition “Fifty Years Later: Revisiting Ax Handle Saturday in Jacksonville, Florida.” The photography exhibit begins with an image of four ax handles against a stark white background. The viewer is challenged to think about what it would feel like to be attacked with one of those solid pieces of wood. Historic photos from Hurst’s book are displayed.

“What’s exciting about the exhibit for me is that it’s on a university campus, with a lot of young people, a lot of inquiring minds,” Hurst says. “If a university does nothing else, it should develop independent thinkers.”

Since 1960, great strides have been made in the fight for racial equality. As contemporary headlines too often remind us, there is still a long way to go.

Dr. Ben Brotemarkle is executive director of the Florida Historical Society and host of the radio program “Florida Frontiers,” broadcast locally on 90.7 WMFE Thursday evenings at 6:30 and Sunday afternoons at 4:00, and on 89.5 WFIT Sunday mornings at 7:00. The show can be heard online at myfloridahistory.org