Asked to think of a case where construction of a modern dam drowned archaeological sites and had other unanticipated environmental impacts, most (at least those of a certain age) would likely recall the Aswan High Dam in Egypt (https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aswan-High-Dam). Yes, the project included relocating the beautiful Abu Simbel temple complex, but imagine all the related sites, workshops, workers houses, markets, etc., now submerged if not forever at least for as long as the dam remains.

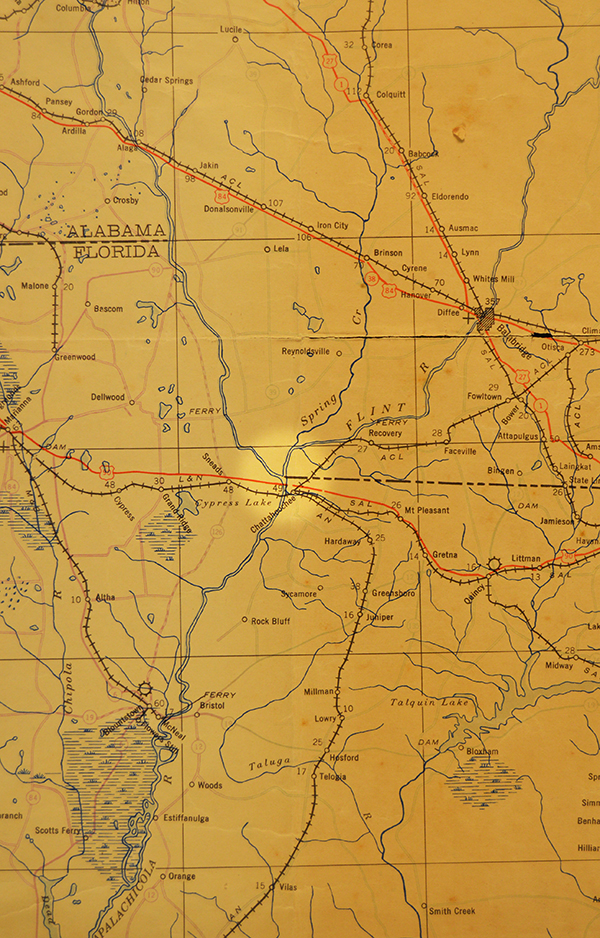

It turns out, as Library of Florida History Archivist Ben Dibiase explains in episode 388 of the Florida Frontiers radio show (https://myfloridahistory.org/frontiers/radio/program/388), we don’t have to go to the Nile for an example, we can find our own, admittedly much smaller, example right at the Florida- Georgia border where the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers converge to form the Apalachicola River (highlighted in this 1942 map).

Courtesy Florida Memory

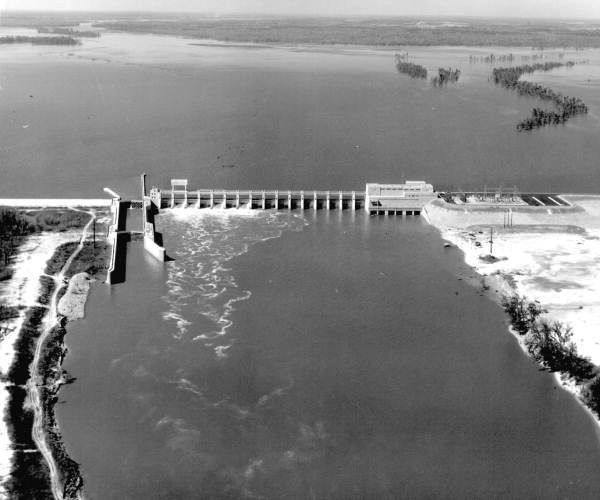

Most of the flooding of the retention basin, now called Lake Seminole, took place between 1952 and 54, so the impact was clear in this 1957 aerial photo.

Courtesy Florida Memory

The creation of the lake for fishing, boating and recreation was considered a bonus.

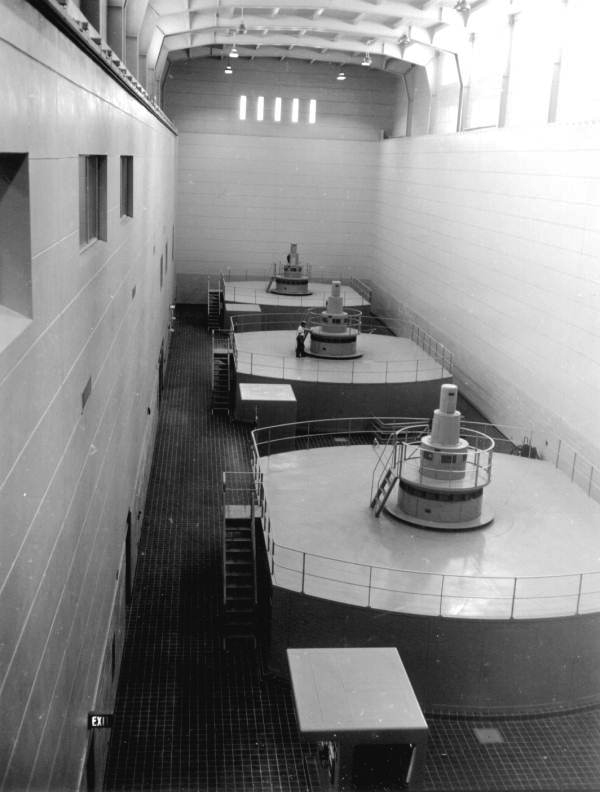

Courtesy Florida Memory

The primary goal of this and several other relatively small dams in rural Georgia and North Florida was to generate electricity for the growing post WWII population. Flood control and even navigation were also factors.

Courtesy Florida Memory

Much of this was the vision attributed to James (Jim) W. Woodruff (on left at the 1947 groundbreaking), a Georgia businessman and civic leader who apparently earned the honor of having his name on the first completed dam by combining undeniable engineering ability with the skills to navigate the halls of Congress.

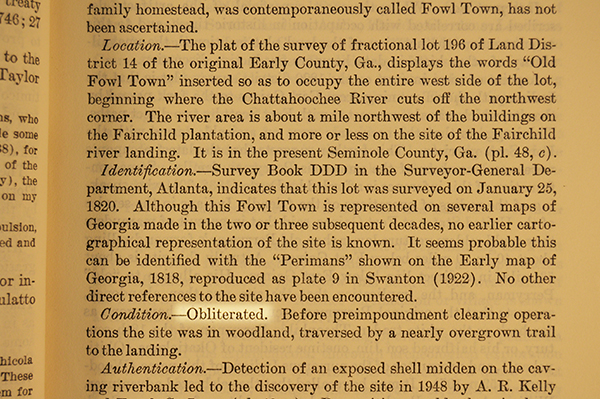

However, as with the Aswan, the collateral impact did not go unnoticed. No less an agency than the Smithsonian Institution was on the case. With support from the Florida Historical Society and the National Park Service, the Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology engaged noted Florida historian Mark F. Boyd (1889-1968) to document as many sites as possible.

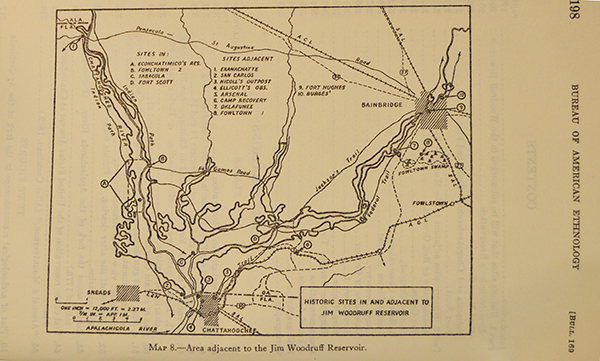

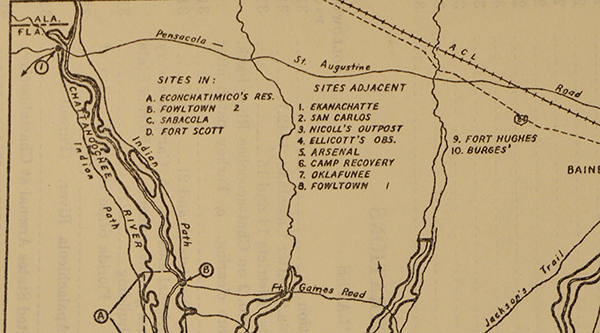

Even as earth was being moved and the waters began to rise, Boyd located sites that would be lost or would be spared.

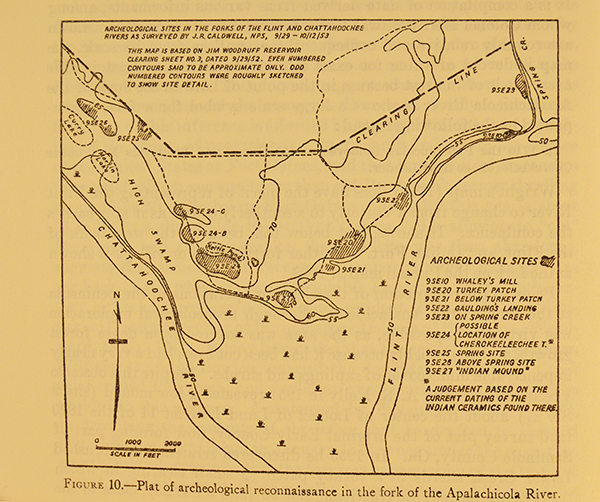

Even as simple spots on a map, the names evoke key moments in Florida’s history and pre-(European) history.

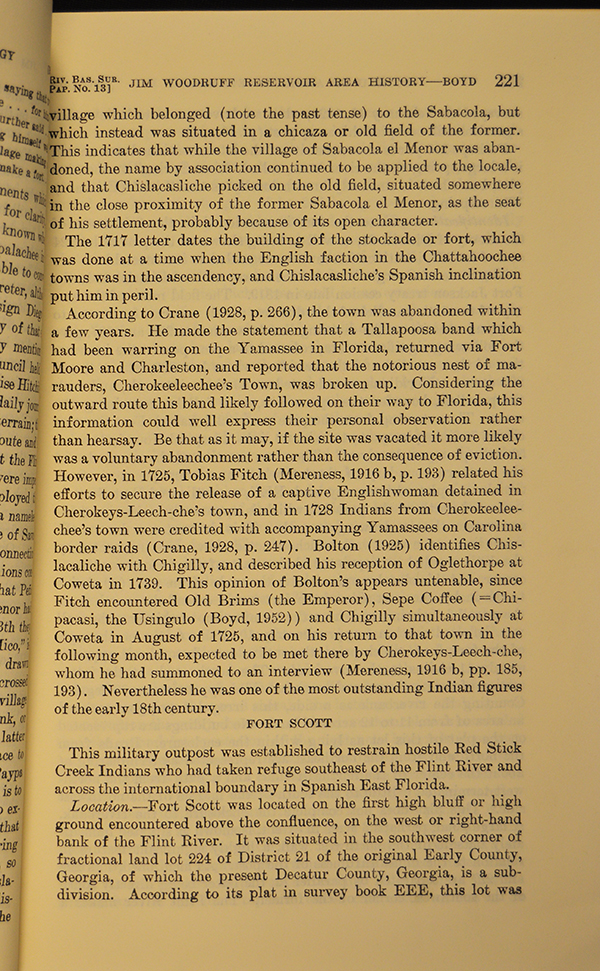

Picking a page at random can immerse a reader in effortless storytelling by a master and a moment later introduce a locale you likely have heard about (https://www.britannica.com/event/Second-Seminole-War).

There are sections that remind a reader the victors do not only write history, they can control the use of the geography as well.

There are charts that clearly document what has been lost forever, leading one to wonder what could be learned if we could apply modern archeological techniques to regions where in the 1950’s one could only note “Indian ceramics found there.”

However, ‘forever’ is a long time. The Woodruff Dam still generates electricity, but not as much as it once did. Most of the water is now being used way upstream in Atlanta. Just as the Aswan is implicated in the decline of the anchovy population in the eastern Mediterranean and the sharply reduced number of fish in the Nile, the Woodruff Dam is part of the argument between Florida and Georgia over water flow into Apalachicola Bay and concerns about invasive species in the entire “ACF Watershed” (https://www.npr.org/2020/07/22/894074674/floridas-oyster-beds-devastated-by-years-of-drought-other-pressures).