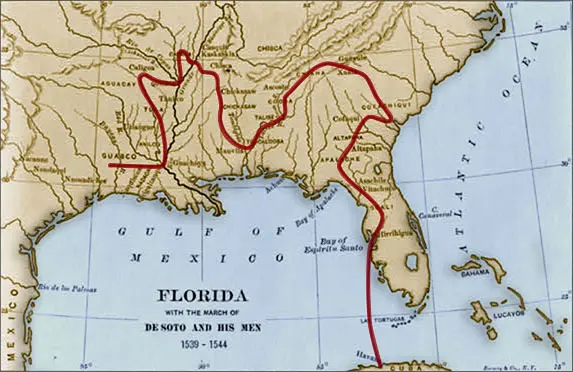

On August 15, 1559, Spanish conquistador Don Tristan de Luna sailed into what is now Pensacola Bay, leading a fleet of twelve ships with 1,500 colonists on board. Their effort to establish a permanent settlement was thwarted by a violent hurricane, which devastated the fleet.

One of the shipwrecks was discovered by underwater archaeologists in 1992, and another in 2006, but until recently, the terrestrial site of the attempted Luna settlement remained a mystery.

“We’re fortunate that we have a letter that Luna wrote after the hurricane, to the King of Spain, describing the storm,” says Greg Cook, assistant professor of maritime archaeology at the University of West Florida. “He said that it raged for twenty-four hours, it hit during the night, with great loss of ships and lives and property, and we know that many of their supplies were destroyed.”

The Emmanuel Point I and Emmanuel Point II shipwrecks continue to provide archaeologists and archaeology students the opportunity to discover artifacts such as stone cannon balls, copper arrow tips to be used with crossbows, ceramics including olive jars, and the bones of livestock, rats, and pet cats.

“What I really like and get excited about are the items that have a personal touch, that tell something about the story,” says John Bratten, chair of the UWF anthropology department. “This is a wooden spoon, it’s probably made out of olive wood, but this would have been a sailor’s personal spoon that he would have carried with him and that he would use to eat. They didn’t have forks. They probably had a knife and a spoon, and that’s what they did.”

Bratten also points out the clear impression of a fingerprint left in a brick more than 450 years ago. The brick was aboard one of Luna’s sunken ships.

While the Luna shipwrecks have yielded fascinating artifacts for decades, it wasn’t until last fall that the exact location of the oldest multi-year European settlement in the United States was discovered in a Pensacola neighborhood.

Former UWF archaeology student Tom Garner was driving through the neighborhood when he saw a cleared lot where a house had been torn down. For 30 years, Garner made a practice of investigating such sites, just to see if any artifacts might have been uncovered.

This time, Garner’s curiosity was rewarded.

“The initial artifact that I found was an olive jar, a fragment, the neck from an olive jar,” says Garner. “These are large, ceramic storage jars for food. They’re very common, one of the most common artifacts on Spanish colonial sites. I understood that that could potentially be Luna, we’re in a spot close to the shipwrecks, but olive jars go as late as maybe 1800 or so, so it wasn’t necessarily Luna. I contacted the University of West Florida archaeology department, and they came and confirmed what it was.”

This summer, professional archaeologists and archaeology students have been working at selected sites throughout the Pensacola neighborhood, excavating artifacts from the Luna settlement.

“We’ve found lots of broken pots,” says Elizabeth Benchley, director of the UWF archaeology institute. “What we hope to be able to find, are areas where different groups of colonists lived together, after the hurricane.” Among the colonists were single soldiers, families, and Aztec Indians from Mexico. “We haven’t found the boundaries of the site yet. We’re still trying to find the edges of where these artifacts are distributed.”

After the 1559 hurricane, life was very difficult for the Luna colonists. The settlement was abandoned in 1561.

“We’re hoping that as we do archaeology here, we can actually see the trash pits, which may give us some evidence as to how they survived,” says UWF associate anthropology professor John Worth.

The exact location of the Luna settlement is being protected for now, but the archaeology work is difficult to miss if you drive through the neighborhood. Carefully dug trenches are apparent in the yards of residential properties.

“Tristan de Luna is this mythical figure in Pensacola,” says neighborhood liaison Tom Garner. “People are thrilled to be part of this project. The response has been tremendous. There’s some bragging going on these days about living in the oldest neighborhood in the United States.”