“Yesterday, December 7th, 1941, a date that will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan,” said President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Within an hour of FDR’s speech on December 8th, 1941, Congress voted to bring the United States into World War II.

A recording of FDR’s address to Congress can be heard as you enter the “Florida Remembers World War II” exhibit, on permanent display at the Museum of Florida History in Tallahassee.

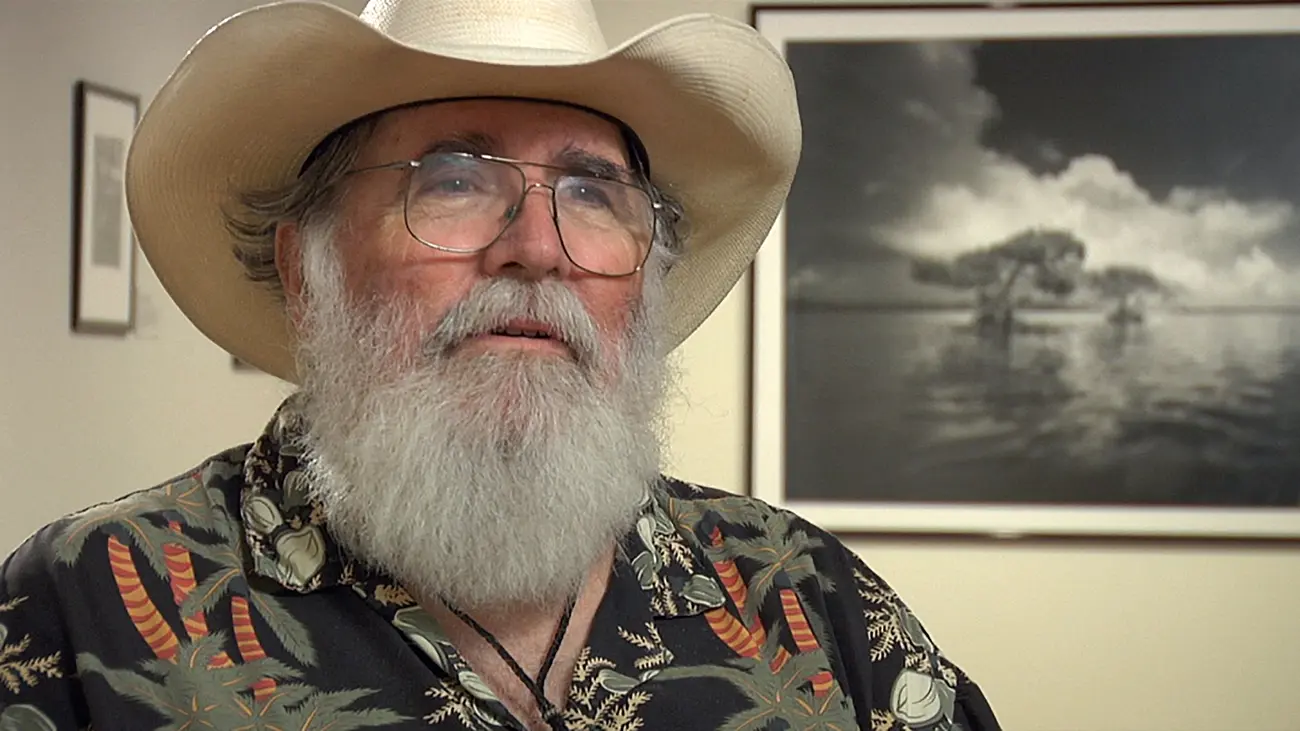

“Florida’s role in World War II was really transformative,” says Bruce Graetz, senior museum curator. “Florida was a relatively rural area before World War II. There was a large influx of servicemen for training during the war, industry like ship building occurred, and by the time the war was over, we’re getting into what’s considered modern Florida.”

According to government statistics, approximately 248,000 Floridians served in World War II. During the war, the population of the state exploded. Key West had 13,000 residents in 1940, and 45,000 by war’s end five years later. The population of Miami doubled to almost 325,000. Florida became an active training ground for American troops.

“Florida’s mild climate and flat terrain allowed for year round training for aviation,” says Graetz. “Camp Blanding [near Starke] is now a National Guard Camp. During World War II, it’s said that population-wise, Camp Blanding was the fourth largest city in the state.”

American troops were provided with amphibious training at Camp Gordon Johnston in Carrabelle, Florida.

“Between those two bases, the three significant U.S. Infantry divisions that went ashore at Normandy had some of their training here in Florida,” Graetz says. “In Daytona Beach, the WACS, the Women’s Auxiliary Corps, developed a training base. Noted African American educator Mary McLeod Bethune had lobbied President Roosevelt to set up a WAC training base, so from 1942 to early 1944, a large number of women trained here in Florida.”

The “Florida Remembers World War II” exhibit includes informational panels, and displays of uniforms, photographs, documents, posters, and personal artifacts.

“Camp Blanding even had a souvenir pillow case that soldiers would buy and send home to sweethearts as a token of where they were training here in Florida,” says Graetz.

More than 50,000 African Americans from Florida entered the military during World War II, primarily as Army support personnel. Some of the famous Tuskegee Airmen were from Florida.

“We’re very fortunate to have had donated for this exhibit, some of the memorabilia of James Polkinghorne, who’s from Pensacola,” says Graetz. “He was a Tuskegee Airman fighter pilot who was flying a strafing mission in Italy when his aircraft went down and he was killed. We have his training yearbook, his posthumous Purple Heart, his pilot’s file, and photographs.”

Florida’s participation in World War II went beyond serving as a training ground for soldiers. Immediately after the United States joined the war, German submarines began attacking supply ships off the coast of Florida.

“Quite a few tankers and freighters were attacked and sunk in Florida,” says Graetz. “In the early months of the war, pretty much the first seven months of 1942, civilians would see a burning tanker [from the shore] and even see a submarine surface. So it really brought the war home to Florida.”

In the 1940s, it was not uncommon to see men working in citrus groves wearing clothing marked with a “P” and “W,” indicating that they were German prisoners of war.

“They were brought back first from the North African campaigns, and some were captured submariners, and then eventually from Europe,” says Graetz. “Germans that were captured and brought to Florida were considered fortunate as opposed to Germans who were captured by the Russians and sent to Siberia. They were held in bases around Florida, and they took classes in English and American Values.”

After the war, Florida’s population expanded by 46%. Many soldiers returned here with their families, or to get an education on the G.I. Bill. To accommodate the influx, the Florida State College for Women became Florida State University.

“Florida produced a booklet called ‘After Victory’ promoting Florida as a state people could move to,” Graetz says.